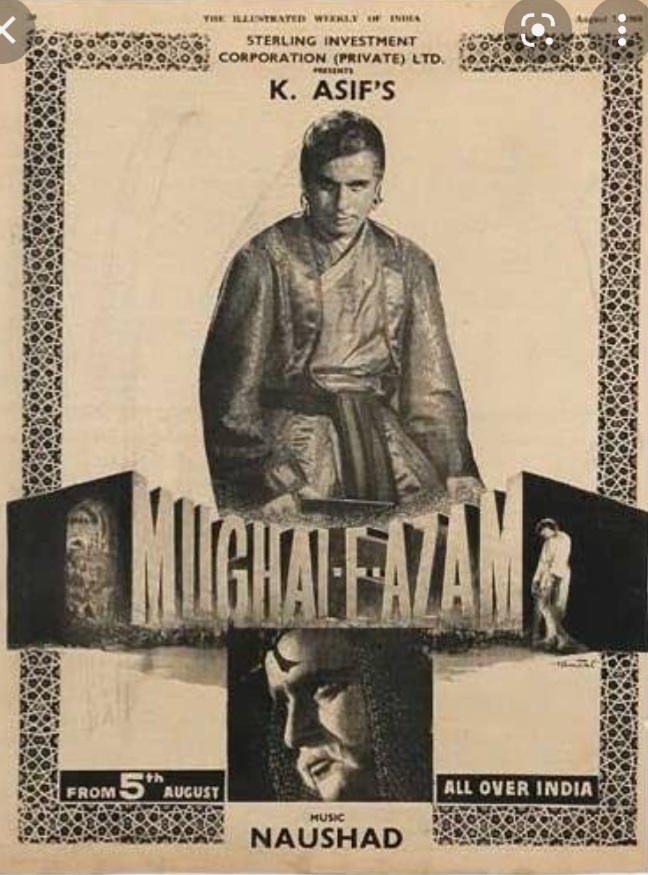

Mughal-e-Azam (The Great Mughal) is a 1960 Indian epic historical drama film directed by K. Asif and produced by Shapoorji Pallonji. It follows the love affair between Mughal Prince Salim and Anarkali, a court dancer. Salim’s father, Emperor Akbar, disapproves of the relationship, which leads to a war between father and son.

The film is widely considered to be a milestone of its genre, earning praise from critics for its grandeur and attention to detail, and the performances of its cast (especially that of Madhubala, who earned a nomination for the Filmfare Award for Best Actress). Film scholars have welcomed its portrayal of enduring themes, but question its historical accuracy.

Emperor Akbar (Prithviraj Kapoor), who does not have a male heir, undertakes a pilgrimage to a shrine to pray that his wife Jodhabai (Durga Khote) give birth to a son. Later, a maid brings the emperor news of his son’s birth. Overjoyed at his prayers being answered, Akbar gives the maid his ring and promises to grant her anything she desires.

Prince Salim (Dilip Kumar), grows up to be spoiled, flippant, and self-indulgent. His father sends him off to war, to teach him courage and discipline. Fourteen years later, Salim returns as a distinguished soldier and falls in love with court dancer Nadira, whom the emperor has renamed Anarkali (Madhubala), meaning pomegranate blossom. The relationship is discovered by the jealous Bahar (Nigar Sultana), a dancer of a higher rank, who wants the prince to love her so that she may one day become queen. Unsuccessful in winning Salim’s love, she exposes his forbidden relationship with Anarkali. Salim pleads to marry Anarkali, but his father refuses and imprisons her. Despite her treatment, Anarkali refuses to reject Salim, as Akbar demands.

Salim rebels and amasses an army to confront Akbar and rescue Anarkali. Defeated in battle, Salim is sentenced to death by his father, but is told that the sentence will be revoked if Anarkali, now in hiding, is handed over to die in his place. Anarkali gives herself up to save the prince’s life and is condemned to death by being entombed alive. Before her sentence is carried out, she begs to have a few hours with Salim as his make-believe wife. Her request is granted, as she has agreed to drug Salim so that he cannot interfere with her entombment.

As Anarkali is being walled up, Akbar is reminded that he still owes her mother a favour, as it was she who brought him news of Salim’s birth. Anarkali’s mother pleads for her daughter’s life. The emperor has a change of heart, but although he wants to release Anarkali he cannot, because of his duty to his country. He therefore arranges for her secret escape into exile with her mother, but demands that the pair are to live in obscurity and that Salim is never to know that Anarkali is still alive.

Director K. Asif (Karimuddin Asif) to make Mughal-e-Azam, he recruited four Urdu writers to develop the screenplay and dialogue: Aman, Wajahat Mirza, Kamaal Amrohi, and Ehsan Rizvi. It is not known how the writers collaborated or shared out their work, but in 2010 The Times of India said that their “mastery over Urdu’s poetic idiom and expression is present in every line, giving the film, with its rich plots and intricate characters, the overtones of a Shakespearean drama.”

According to Dilip Kumar, “Asif trusted me enough to leave the delineation of Salim completely to me.” Kumar faced difficulty while filming in Rajasthan owing to the heat and the body armour he wore. Madhubala, who had been longing for a significant role. Upon signing the film, Madhubala was advancely paid a sum of ₹1 lakh, which was the highest for any actor/actress at that time. To become the character of Emperor Akbar, Prithviraj Kapoor was reported to have “relied completely on the script and director”. Prior to make-up, Kapoor would declare, “Prithviraj Kapoor ab jaa rahaa hai” (“Prithviraj Kapoor is now going”); after make-up, he would announce, “Akbar ab aa rahaa hai” (“Akbar is now coming”). Kapoor faced difficulty with his heavy costumes, and suffered blisters on his feet after walking barefoot in the desert for a sequence. Lance Dane, a photographer who was on set during the filming, recalled that Kapoor struggled to remember his lines in some scenes; he mentioned one scene in particular that Kapoor required 19 takes to get right. At the time of filming, Kapoor who was on a diet, was told by Asif to regain the lost weight for his portrayal of Akbar.

The production design of the film, led by art director M. K. Syed, was extravagant, and some sets took six weeks to erect. The film, mostly shot in studio sets designed to represent the interior of a Mughal palace, featured opulent furnishings and water features such as fountains and pools, generating the feel of a Hollywood historical epic of the period. The song “Pyar Kiya To Darna Kya” was filmed in Mohan Studios on a set built as a replica of the Sheesh Mahar in the Lahore Fort. A much-discussed aspect was the presence of numerous small mirrors made of Belgian glass, which were crafted and designed by workers from Firozabad. The set took two years to build and cost more than ₹1.5 million, more than the budget of an entire Bollywood film at the time.

Artisans from across India were recruited to craft the props. The costumes were designed by Makhanlal and Company, and Delhi-based tailors skilled in zardozi embroidery stitched the Mughal costume. The footwear was ordered from Agra, the jewellery was made by goldsmiths inderabad, the crowns were designed in Kolhapur, and blacksmiths from Rajathan manufactured the armoury (which included shields, swords, spears, daggers, and armour). The zardozi on costumes were also stitched by designers from Surat. A statue of Lord Krishna, to which Jodhabai prayed, was made of gold. In the scenes involving an imprisoned Anarkali, real chains were placed on Madhubala. The battle sequence between Akbar and Salim reportedly featured 2,000 camels, 400 horses, and 8,000 troops, mainly from the Indian Army’s Jaipur cavalry, 56th Regiment. Dilip Kumar has spoken of the intense heat during filming of the sequence in the desert of Rajasthan, wearing full armour.

Principal photography for Mughal-e-Azam began in the early 1950s. Some film sequences were shot with up to 14 cameras, significantly more than the norm at that time. There were many difficulties with the film’s lighting; cinematographer Mathur reportedly took eight hours to light a single shot. In total, 500 days of shooting were needed, compared to a normal schedule of 60 to 125 shooting days at the time. The song “Pyar Kiya To Darna Kya” was filmed on a set built Sheesh Mahal. Owing to the very large size of the Sheesh Mahal set, the lighting was provided by the headlights of 500 trucks and about 100 reflectors. The presence of the mirrors on the set caused problems, as they sparkled under the lights. Foreign consultants, including British director David Lean, told Asif to forget the idea since they felt that it was impossible to film the scene under the intense glare. Asif confined himself to the set with the lighting crew, and subsequently overcame the problem by covering all the mirrors with a thin layer of wax, thereby subduing their reflectivity. Mathur also used strategically placed strips of cloth to implement “bounce lighting”, which reduced the lare.

A number of problems and production delays were encountered during filming, to the extent that at one point Asif considered abandoning the project. Kumar defended the long duration of filming, invoking the massive logistics of the film and explaining that the entire cast and crew were “acutely conscious of the hard work they would have to put in, as well as the responsibility they would have to shoulder.”

The production also suffered from financial problems, and Asif exceeded the budget on a number of occasions. The final budget of the film is a subject of debate. Mughal-e-Azam the most expensive Indian film of the period. A number of estimates put the film’s inflation-adjusted budget at ₹500 million to ₹2 billion.

Sohrab Modi’s Jhansi Ki Rani (1953) was the first Indian film to be shot in colour, and by 1957, colour production had become increasingly common. Asif filmed one reel of Mughal-e-Azam, including the song “Pyar Kiya To Darna Kya”, in Technicolor. Impressed by the result, he filmed three more reels in Technicolor, near the story’s climax. After seeing them, he sought a complete re-shoot in Technicolor, angering impatient distributors who were unwilling to accept further delays. Asif subsequently released Mughal-e-Azam partially coloured, although he still hoped to see the full film in colour.

A number of songs were edited out owing to the running time, which in the end was 197 minutes. Almost half of the songs recorded for the film were left out of the final version.

Mughal-e-Azam is a family history highlighting the differences between father and son, duty to the public over family, and the trials and tribulations of women, particularly of courtesans. According to Rachel Dwyer, author of the book Filming the Gods: Religion and Indian Cinema, the film highlights religious tolerance between Hindu and Muslims. Examples include the scenes of Hindu Queen Jodhabai’s presence in the court of the Muslim Akbar, the singing of a Hindu devotional song by Anarkali, and Akbar’s participation in the Janmashtami celebrations, during which Akbar is shown pulling a string to rock a swing with an idol of Krishna on it. Throughout the film there is a distinct depiction of Muslims as the ruling class who not only dressed differently but also spoke in complex Persianised dialogue. They are made to appear “distinct and separate from the mainstream.”

Film scholar Stephen Teo posits that Mughal-e-Azam is a “national allegory”, a stylistic way of appropriating history and heritage to emphasise the national identity. He believes the arrogance of Bahar represents the power of the state and that Anarkali’s emotion, which is highly personal, represents the private individual. Teo states that the theme of romantic love defeating social class difference and power hierarchy, as well as the grandeur of the filming, contribute to the film’s attractiveness. Gowri Ramnarayan of The Hindu has also emphasised the power of the dialogues in the film in that they “create not only the ambiance of this period drama, but also etch character and situation. Every syllable breathes power and emotion.”

The soundtrack was composed by music director Naushad, and the lyrics were written by Shakeel Badayuni. After conceiving the idea of the film, Asif visited Naushad and handed him a briefcase containing money, telling him to make “memorable music” for Mughal-e-Azam. Offended by the explicit notion of money as a means of gaining quality, Naushad threw the notes out of the window, to the surprise of his wife. She subsequently made peace between the two men, and Asif apologised. With this, Naushad accepted the offer to direct the film’s soundtrack. As with most of Naushad’s soundtracks, the songs of Mughal-e-Azam were heavily inspired by Indian classical music and folk music, particularly ragas such as Darbari, Durga, used in the composition of “Pyar Kiya To Darna Kya”, and Kedar, used in “Bekas Pe Karam Keejeye”. The soundtrack contained a total of 12 songs, which were rendered by playback singers and classical music artists. These songs account for nearly one third of the film’s running time.

At the time of the release of Mughal-e-Azam, a typical Bollywood film would garner a distribution fee of ₹300,000–400,000 per territory. Asif insisted that he would sell his film to the distributors a t no less than ₹700,000 per territory. Subsequently, the film was actually sold at a price of ₹1.7 million per territory, surprising Asif and the producers. Thus, it set the record for the highest distribution fee received by any Bollywood film at that time.

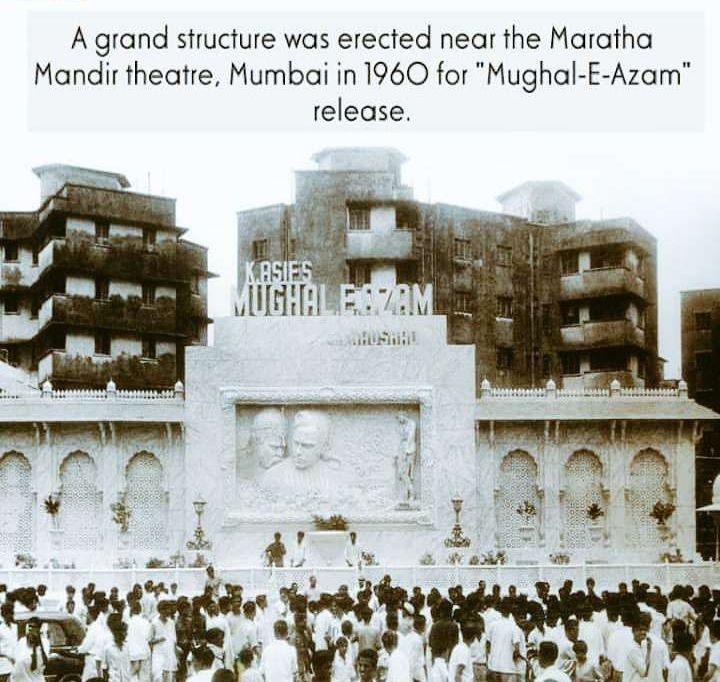

The premiere of Mughal-e-Azam was held at the then-new 1,100-capacity Maratha Mandir cinema in Mumbai. Mirroring the nature of the film, the cinema’s foyer had been decorated to resemble a Mughal palace, and a 40-foot (12 m) cut-out of Prithviraj Kapoor was erected outside it. The Sheesh Mahal set was transported from the studio to the cinema, where ticket holders could go inside and experience its grandeur. Invitations to the premiere were sent as “royal invites” shaped like scrolls, which were written in Urdu and made to look like the Akbarnama, the official chronicle of the reign of Akbar. The premiere was held amidst great fanfare, with large crowds and an extensive media presence, in addition to hosting much of the film industry. The film’s reels arrived at the premiere cinema atop a decorated elephant, accompanied by the music of bugles and shenai.

The day before bookings for the film opened, a reported crowd of 100,000 gathered outside the Maratha Mandir to buy tickets. The tickets, the most expensive for a Bollywood film at that time, were dockets containing text, photographs and trivia about the film, and are now considered collector’s items. Bookings experienced major chaos, to the extent that police intervention was required. It was reported that people would wait in queues for four to five days, and would be supplied food from home through their family members. Subsequently, the Maratha Mandir closed bookings for three weeks.

Mughal-e-Azam was released on 5 August 1960 in 150 cinemas across the country, establishing a record for the widest release for a Bollywood film. It became a major commercial success, earning ₹4 million in the first week, eventually earning a net revenue of ₹55 million, and generating a profit of ₹30 million for the producers. Mughal-e-Azam also experienced a long theatrical run, screening to full capacity at the Maratha Mandir for three years. The film thus became the highest-grossing Bollywood film of all time. In terms of gross revenue, Mughal-e-Azam earned ₹110 million.

According to the online box office website Box Office India in January 2008, the film’s adjusted net revenue would have amounted to ₹1,327 million, ranking it as an “All-Time Blockbuster”. According to financial newspaper Mint, the adjusted net income of Mughal-e-Azam is equivalent to ₹13 billion in 2017.

Mughal-e-Azam received almost universal acclaim from Indian critics; every aspect of the film was praised. A review dated 26 August 1960 in Filmfare called vitv av “history-makingv film … the work of a team of creative vartists drawn from different spheres of the art world”. It was also described as “a tribute to imagination, hard work and lavishness of its maker, Mr. Asif. For its grandeur, its beauty, and then performances of the artists it should be a landmark in Indian films.”

Since 2000, reviewers have described the film as a “classic”, “benchmark”, or “milestone” in the history of Indian cinema. Dinesh Raheja of Rediff called the film a must-see classic, saying “a work of art is the only phrase to describe this historical whose grand palaces-and-fountains look has an epic sweep and whose heart-wrenching core of romance has the tenderness of a feather’s touch.”

K. K. Rai, in his review for Stardust stated, “it can be said that the grandeur and vintage character of Mughal-e-Azam cannot be repeated, and it will remembered as one of the most significant films made in this country.” Laura Bushell of the BBC rated the film four out of five stars, considering it to be a “benchmark film for both Indian cinema and cinema grandeur in general”, and remarking that Mughal-E-Azam was an epic film in every way.

Nasreen Munni Kabir, author of The Immortal Dialogue of K. Asif’s Mughal-e-Azam, compared the film to the Kohinoor diamond for its enduring worth to Indian cinema. Outlook in 2008, and Hindustan Times, in 2011, both declared that the scene in which Salim brushes Anarkali with an ostrich feather was the most erotic and sensuous scene in the history of Indian cinema.

At the 1961 National Film Awards, Mughal-e-Azam won the National Film Award for Best Feature Film in Hindi. In the 1961 Film Awards, Mughal-e-Azam was nominated in seven categories: Best Film, Best Director (K. Asif), Best Actress (Madhubala), Best Singer, Best Music (Naushad), Best Cinematography (Mathur), Best Dialogue (Aman, Wajahat Mirza, Kamaal Amrohi, and Ehsan Rizvi), winning the awards for Best Film, Best Cinematography, and Best Dialogue.

Mughal-e-Azam was the first black-and-white Hindi film to be digitally coloured and the first to be given a theatrical re-release. The Sterling Investment Corporation, the negative rights owner and an arm of the Shapoorji Pallonji Group, undertook restoration and colourisation of Mughal-e-Azam and assigned Deepesh Salgia as Project Designer and Director. They initially approached Hollywood executives for help, but found the sales quotations, ranging from $12–15 million, too high. In 2002, Umar Siddiqui, managing director of the Indian Academy of Arts and Animation (IAAA), proposed to enhance it digitally at a fraction of the cost. To convince the Shapoorji Pallonji Group, one of India’s wealthiest companies, of the commercial viability of the project, the IAAA colourised a four-minute clip and showed it to them. They approved and gave the project the go-ahead. Shapoorji Mistry, grandson of producer Shapoorji Pallonji Mistry, thought it a fitting tribute to complete his grandfather’s unfinished dream of colourising the entire film.

The first step towards colourisation was the restoration of the original negatives, which were in poor condition owing to extensive printing of the negative during the original theatrical release. Costly and labour-intensive restoration was essential before colourisation could be carried out. The negative was cleaned of fungal growth, damaged portions were restored, and missing parts of frames were re-instated. After cleaning, each of the 300,000 frames of the negative was scanned into a 10 megabytes -sized file and then was digitally restored. The entire restoration work was undertaken by Acris Lab, Chennai. The dialogues in the original soundtrack were also in a bad state of preservation, which necessitated having the sound cleaned at Chace Studio in the United States. The background score and the entire musical track was recreated by Naushad and Uttam Singh. For the songs, the original voices of the singers like Lata Mangeshkar, Bade Ghulam Ali Khan and Mohammed Rafi were extracted from the original mixed track and the same were recreated with re-recorded score in 6.1 surround sound.

The process of colourisation was preceded by extensive research. The art departments visited museums and studied the literature for background on the typical colours of clothing worn at that time. Siddiqui studied the technology used for the colourisation of black-and-white Hollywood classics. The team also approached a number of experts fo r guidance and suggestions, including Dilip Kumar, and a historian from the Jawaharlal Nehru University in Delhi. To undertake the colourisation, Siddiqui brought together a team of around 100 individuals, including computer engineers and software professionals, and organised a number of art departments.

The colourisation team spent 18 months developing software for colouring the frames, called “Effects Plus”, which was designed to accept only those colours whose hue would match the shade of grey present in the original film. This ensured that the colours added were as close to the real colour as possible; the authenticity of the colouring was later verified when a costume used in the film was retrieved from a warehouse, and its colours were found to closely match those in the film. Every shot was finally hand-corrected to perfect the look. The actual colourisation process took a further 10 months to complete. Siddiqui said that it had “been a painstaking process with men working round the clock to complete the project.”

The colour film was dispatched to London and arrived a month later. In this weekly column, we revisit gems from the golden years of Hindi cinema. This week, we revisit the 1960 release Mughal-e-Azam.

The film’s colour version was released theatrically on 12 November 2004, in 150 prints across India, 65 of which were in Maharashtra. The new release premiered at the Eros Cinema in Mumbai. Dilip Kumar, who had not attended the original premiere, was in attendance. The colour version was edited to a running time of 177 minutes, as compared to the original version’s 197 minutes. The new release also included a digital reworked soundtrack, produced with the assistance of Naushad, the original composer. The release on the festive Diwali weekend. It became the 19th highest grossing Bollywood film of the year.

Mughal-e-Azam became the first full-length feature film colourised for a theatrical re-release; although some Hollywood films had been colourised earlier, they were only available for home media. It was subsequently selected for seven international film festivals, including the 55th Berlin International Film Festival. Upon release, the film drew crowds to the cinemas, with an overall occupancy of 90 per cent. Subsequently, it completed a 25-week run. While some critics complained that the colours were “psychedelic” or “unnatural”, others hailed the effort as a technological achievement. Film critic Kevin Thomas of the Los Angeles Times remarked that while colourising was not a good idea for most black-and-white classics, it was perfect in this particular instance. He compared it to films by Cecil B. DeMille and to Gone With the Wing (1939) for its larger-than-life storytelling. The BBC’s Jaspreet Pandohar, observing that the film was “restored in appealing candy-colours and high quality sound”. Other critics have said that they prefer the black and white version.

In 2006, Mughal-e-Azam became only the fourth Indian film certified for showing in Pakistan since the 1965 ban on Indian Cinema, and was released with a premiere in Lahore. It was distributed by Nadeem Mandviwala Entertainment, at the request of Asif’s son, Akbar Asif.

In October 2016, producer Feroz Abbas Khan premiered a stage play based on the film with a cast of over 70 actors and dancers at Mumbai’s NCPA Theatre.

Mughal-e-Azam might be over six decades old but it still represents the hard work and resilience of a team that created perfection on screen that can’t be challenged till date. It was absolutely impossible to film the sequence as the director had in mind.

Photos courtesy Google. Excerpts taken from Google.