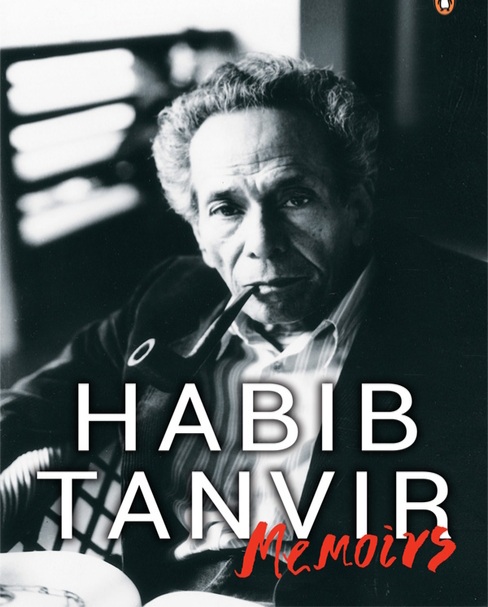

Habib Tanvir was one of the most popular Indian Urdu, Hindi playwrights, a theatre director, poet and actor. Habib Tanvir Scripted a new chapter in Indian Theatre’s History. He was the writer of plays such as, ‘Agra Bazar, (1954) and ‘Charandas Chor, (1975). A pioneer in Urdu and Hindi Theatre, he was most known for his work with Chhattisgarhi tribals, at the Naya Theatre, a theatre company he founded in 1959 in Bhopal. He went on to include indigenous performance forms such as nacha, to create not only a new theatrical language, but also milestones such as Charandas Chor, Gaon ka Naam Sasural, Mor Naam Damad and Kamdeo ka Apna Basant Ritu ka Sapna. He often used non-professionally-trained village performers in his works.

For him, true “theatre of the people” existed in the villages, which he strived to bring to the urban “educated”, employing both folk performers as actors alongside urban actors. He was the last of pioneering actor-managers in Indian theatre, which included Sisir Bhaduri, Utpal Dutt and Prithviraj Kapoor, and often he managed plays with a mammoth cast, such as Charandas Chor, which included an orchestra of 72 people on stage and Agra Bazaar, with 52 people.

During his lifetime he won several national and international awards, including the Sangeet Natak Akademi Award in 1969, Jawarharlal Nehru Fellowship in 1979, Padma Shri in 1983, Kalidas Samman 1990, Sangeet Natak Akademi Fellowship in 1996, and the Padma Bhushan in 2002. Apart from that he had also been nominated to become a member of the Upper House of Indian Parliament, the Rajya Sabha (1972–1978).

Early in life, he started writing poetry using his pen name Takhallus. Soon after, he assumed his name, Habib Tanvir.

In 1945, he moved to Bombay, and joined All India Radio (AIR) Bombay as a producer. While in Bombay, he wrote songs for Urdu and Hindi films and even acted in a few of them. He also joined the Progressive Writers’ Association (PWA) and became an integral part of Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA) as an actor. Later, when most of the prominent IPTA members were imprisoned for opposing the British rule, he was asked to take over the organisation.

When Tanvir moved to Delhi in 1954, the theatre scene in the national capital was dominated by groups that focused on the 19th and 20th century European models of theatre. His ‘Agra Bazaar’ stood in complete contrast, in terms of content and form. Agra Bazaar is a homage to Nazir Akbarabadi, an 18th-century Urdu poet who wrote in a style that was disregarded by poetic norms of his times. Tanvir cast a mix of people — educated middle-class actors, street artists and even regular residents of Okhla village in Delhi and used street language in his play. In fact, the play was first not staged in a confined area or a closed space, but in an actual bazaar.

Although the play was about him, he was nowhere on the stage. But his presence could be felt in the texture of the play. The reason was, as Habib Tanvir wrote in the preface: “I wanted to make Nazir’s poetry and not his life the foundation of the theatre. During writing the play it occurred to me that not bringing Nazir to the stage would be better. In this way, not just many crucial stages of my themes were traversed, it also influenced my technique in many ways and technique and themes came to be blended.”

The play, Agra Bazar, was radical in its engagement with popular culture and use of street language. It gave immense joy to the theatre lovers. In the first version of Agra Bazar the plot was entirely cantered on the Kakri-wala, who finds it difficult to sell his kakri until he gets Nazir to write a poem on it. He sings this poem and does brisk business. Gradually, another strand was added to the play, which concerned a prostitute and a police constable.

It was not an easy job to recreate era of the people’s poet Nazir Akbarabadi on the stage but Habib Tanvir accomplished this feat without showing the poet, in his play Agra Bazar. The play is a masterpiece. The bookseller, kakdiwala, kiteseller, darogha, tawaif, the street performer, everybody wanted Nazir to pen a Nazm for him.

Laddoo-wala, madari, eunuch, kanmeliya [one who cleans ear], tarbooz-seller, poet, conjurer, faqir and vendors are all part of the enchanting drama. Tanvir himself wrote that he didn’t want to focus on Nazir’s philosophy and his humanism, harmony rich insight about diversity of Indian culture and his popularity among the masses.

With folk artists like Gyarasa, a nutt, street acrobat teenager Sangeeta, two real faqirs of Ajmer who played iron rings and sticks while singing the nazms and artists from rural parts of the country, Tanvir staged the Agra Bazar in Okhla. It was an instant success. The Kakdi-wala is sad that nobody is buying the cucumber. Like tarbooz-wala and laddoo-wala, he also follows suit and gets a nazm from Nazir. The Kakdi-wala happily goes back and as he gives a call to the buyer, singing the nazm, his basket gets emptied fast.

It is an experience of lifetime to watch Agra Bazaar that became a landmark in Indian theatre. Over the years, the cast changed and there were a few modifications in the drama, but it remained one of the most popular plays ever and wherever it was staged, it drew jam-packed audiences.

The vocabulary that has now become extinct, the interesting conversations, the variety of articles at every shop like the patangbaaz naming dozens of varieties of kites–ranging from kajkulah to chamchaqa and manjhdar, the selection of artists who looked so real that the you also found yourself sent into the era, turned Agra Bazar a magical masterpiece.

Habib Tanvir brilliantly portrays the two opposite poles on the stage. On the one hand, there is a kite shop, and on the other, a bookshop and in the middle lies the bazaar. Thus, he brought the entire social spectrum to the stage in one stroke. This had a lot tok do with his democratic consciousness, which is beautifully reflected in his plays. He shares once that in Agra Bazar that he wanted to show the contrast to the working-class, that the educated privileged of Nazir’s time praised him as a person, but totally overlooked him as a poet. And this was the point that gave him an idea of the bookseller, who helps the play move ahead and whose shop becomes the two opposing poles of the marketplace. The play is marked by its imaginative plot and its inventive and simple story.

In 1955, when he was in his 30s, Habib moved to England. There, he trained in Acting at Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts (RADA) and in Direction at Bristol Old Vic Theatre School (1956). For the next two years, he travelled through Europe, watching various theatre activities. One of the highlights of this period, was his eight-month stay in Berlin in 1956, during which he got to see several plays of Bertolt Brecht, produced by Berliner Ensemble, just a few months after Brecht’s death. This proved to have a lasting influence on him, as in the coming years, he started using local idioms in his plays, to express trans-cultural tales and ideologies. This, over the years, gave rise to a “theatre of roots”, which was marked by an utter simplicity in style, presentation and technique, yet remaining eloquent and powerfully experiential.

A deeply inspired Habib returned to India in 1958 and took to directing full-time. He produced Mitti ki Gaadi a post-London play, based on Shudraka’s Sanskrit work, ‘Mrichakatika’. It became his first important production in Chhattisgarhi. This was the result of the work he had been doing since his return – working with six folk actors from Chhattisgarh. He went on to found “Naya Theatre”, a theatre company in 1959.

In his exploratory phase, i.e. 1970–73, he broke free from one more theatre restriction – he no longer made the folk artistes, who had been performing in all his plays, speak Hindi. Instead, the artistes switched to Chhattisgarhi, a local language they were more accustomed to. Later, he even started experimenting with “Pandavani”, a folk singing style from the region and temple rituals. This made his plays stand out amidst the gamut of plays which still employed traditional theatre techniques like blocking movements or fixing lights on paper. Spontaneity and improvisation became the hallmark of his new theatre style, where the folk artistes were allowed greater freedom of expression.

Gaon Naam Sasural, Mor Naam Damad, first directed by Habib Tanvir in 1973, is a light comedy and folk tale. The story starts with the harvest season festival of Chher-Chhera and revolves around the love of two youngsters, Jhanglu and Manti. The comedy kicks in when Jhanglu pretends to be a brother-in-law to Manti, and uses tricks to elope, after her father fixes her marriage with an old village head. The folk songs of Chhattisgarh are a part of the play throughout.

Habib Tanvir once said, “This play was like a milestone in my theatre journey and this play also helped me to give a way to my next production, Charandas Chor.”

In 1975, theatrical landmark on Habib’s artistic path is Charandas Chor. (Charandas, The Thief). The protagonist Charandas is a thief with a kind heart — he can’t bring himself to rob the helpless or the poor, but runs around policemen, greedy landlords and their strongmen and other such pillars of the establishment. Here the irony is that the whole system is corrupt. The audience sympathises with him.

This play immediately established a whole new idiom in modern India theatre; whose highlight was Nach – a chorus that provided commentary through song. Charandas Chor won him the Fringe Firsts Award at Edinburgh International Drama Festival in 1982, and in 2007, it was included in the Hindustan Times’ list of ‘India’s 60 Best works since Independence which said : “an innovative dramaturgy equally impelled by Brecht and folk idioms, Habib Tanvir seduces across language barriers in this his all-time biggest hit about a Robin Hood-style thief.” Later, he collaborated with Shyam Benegal, when he adapted the play to a feature-length film, by the same name, starring Smita Patil and Lalu Ram.

Habib Tanvir experimented with both content and form in his plays like Agra Bazar and Charandas Chor. Naya Theatre marked his lifelong quest to create a new form. His oeuvre is an emblem of modern theatre in India.

He was awarded the prestigious Jawarharlal Nehru Fellowship in 1979 for research on Relevance of Tribal Performing Arts and their Adaptability to A changing Environment. In 1980, he directed the play Moti Ram ka Satyagraha for Janam (Jan Natya Manch) on the request of Safdar Hashmi.

During his career, Habib has acted in over nine feature films, including Richard Attenborough’s film Gandhi (1982).

His first brush with controversy came about in the 1990s, with his production of a traditional Chhattisgarhi play about religious hypocrisy, Ponga Pandit. The play was based on a folk tale and had been created by Chhattisgarhi theatre artists in the 1930s. Though he had been producing it since the sixties, in the changed social climate after the Babri Masjid demolition, the play caused quite an uproar amongst Hindu fundamentalists, especially the Rashtriya Swayamsewak Sangh (RSS), whose supporters disrupted many of its shows, and even emptied the auditoriums, yet he continued to show it all over.

His Chhattisgarhi folk troupe, surprised again, with his rendition of Asghar Wajahat’s ‘Jisne Lahore Nahin Dekhya’ in 1992. Then in 1993 came ‘Kamdeo Ka Apna Basant Ritu Ka Sapna’, Tanvir’s Hindi adaptation of Shakespeare’s ‘A Midsummer Night’s Dream‘. In 1995, he was invited to the United States by the Chicago Actors Ensemble, where he wrote his only English language play, ‘The Broken Bridge’. In 2002, he directed ‘Zahareeli Hawa’, a translation of Bhopal by the Canadian-Indian playwright Rahul Varma, based on the Bhopal Gas Tragedy. During his illustrious career he brought works from all genres to stage, from ancient Sanskrit works by Shudraka, Bhasa, Vishakhadatta and Bhavabhuti; to European classics by Shakespeare, Molière and Goldoni; modern masters Brecht, Garcia, Lorca, Gorky, and Oscar Wilde; Tagore, Asghar Wajahat, Shankar Shesh, Safdar Hashmi, Rahul Varma, stories by Premchand, Stefan Zweig and Vijaydan Detha, apart from an array of Chhattisgarhi folk tales.

Director, actor, playwright, poet, Habib Tanvir was a man of many colors, all rolled into one. His vibrant personality and talent are fondly remembered by many in theatre and cinema.

Actor Naseeruddin Shah once said that he cites the example of Habib Tanvir as one of those who has guided actors even in their darkest of days.

“I remember Tanvir ji as a very witty man, he would make everyone around him laugh. He would always tell us important things during the production very casually. The first time I met him was when Agra Bazaar was staged at Delhi’s Indraprastha College for women. He had this enigmatic quality that would leave all of us in awe. He would sit in a corner, engrossed in work but would keep a keen eye on everything and everyone. It’s like he would make a small tilt of the head and would know what is going on in the rehearsals. There was an energy about him all the time,” actor Sayani Gupta told The Print, remembering her experiences while working with the legendary playwright.

In modern theatre, the name Habib Tanvir is prominent and needs no formal introduction. He was a renowned Hindi and Urdu playwright, a great director, actor, manager, poet, and one of the most important theatre personalities. He was also a progressive thinker, a humanist and a people’s artiste, who created a theatre embedded in the Indian soil and the realisation of our people, reflecting modern-day awareness. Noted film director Shyam Benegal once said about him: “Habib Tanvir was unquestionably one of the greatest theatre producers, directors, actors and writers, and a pioneer of Hindustani theatre.”

Habib Tanvir had an incredible understanding of the freedom of expression and the social responsibility of artists. He experimented with both content and form. His integrity and imagination always kept him in good stead. He made his distaste for orientalism clear and was always conscious of the danger of appropriation. With his collaborative and empowering approach, he scripted a new chapter in the history of Indian Theatre. Naya Theatre marked Tanvir’s lifelong quest to create a new form of theatre that moved away from the realistic Stanislavskian tradition that insisted on training actors to bring believable emotions to their performances.

In 2010, at the 12th Bharat Rang Mahotsav, the annual theatre festival of National School of Drama, Delhi, a tribute exhibition dedicated to life, works and theatre of Habib Tanvir and B. V. Karanth was displayed. The 13th Bharat Rang Mahotsav opened with an Assamese adaptation of his classic play Charandas Chor, directed by Anup Hazarika, a NSD graduate.

Photos courtesy Google. Excerpts taken from Google.