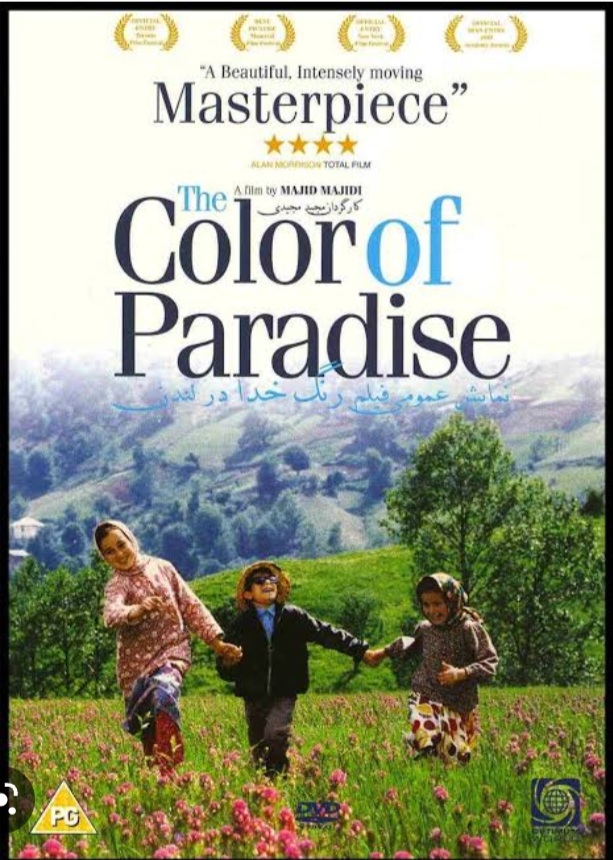

The Color of Paradise (The Color of God) is a 1999 Iranian Film written and directed by Majid Majidi.

The story concerns an eight-year-old boy who is blind and lives in a remote village with his widowed father, his two sisters, and his grandmother. The film opens with slow disclosure: a black screen and the sounds of children identifying tapes that are being played in a cassette recorder. When visuals appear, the last day of class before the summer break at a school for the blind in Tehran. Soon all the children are picked up into the loving arms of their parents, except one boy, Mohammed, whose father is late in coming. There is a remarkable sequence in which he hears the peep of a chick which has fallen from its nest. The boy finds the chick, gently takes it in his hand and then climbs a tree, listening for the cries of the lost one’s nest-mates. He replaces the bird in its nest. God, who knows when a sparrow falls, has had help this time from a little blind boy.

When the father, Hashem, arrives, he tells the school officials that he is too poor to take care of a blind boy and asks if he can be kept at the school. The school officials inform him that this is not possible, and it is clear that this is going to be a key issue for much of the film. Then the father takes his son back to his village situated in the lush, green Caspian area of Iran. Since much of Iran has a stark, arid landscape, the Caspian area, with its groves and wildflowers, has a special attraction for many Iranians. So an Iranian viewer would likely be even more mindful of Mohammad’s inability to see and enjoy the richly colourful landscapes shown throughout the film. Nevertheless, Mohammad’s intimate encounter with the natural world of his village, assisted by the close relationships he has with his two sisters and grandmother, is full of joy and wonder. He wants to learn the language of nature, just as he has had adeptly learned braille at his school, so that he can go on and participate in all the dialogues of nature’s creatures.

The father, meanwhile, is struggling to fashion a satisfactory life for himself in the adult world of affairs. Widowed for the past five years and with a young family to support, he hopes to find the companionship of another wife – not so easy when you are neither young nor rich and are living in the socially-restricted circumstances of rural Iran. Having a handicapped boy to raise is a further burden that causes him to curse his bad fortune. He has his heart set on a young woman nearby whose fiancé has recently died, and she appears to be receptive to his interest. Mohammad’s grandmother, observes this situation with concern. She loves little Mohammad and quietly scolds her son for placing his own personal desires above that of his family.

Hashem, who is a widower, now wants to marry a local woman and prepares for the wedding. He approaches the woman’s parents with gifts, and they give him their blessing. He attempts to hide the fact that his son is blind because he fears that the girl’s family will see it as a bad omen.

Meanwhile, Mohammad happily roams around the beautiful hills of his village with his sisters. He touches and feels the nature around him, counting the sounds of animals and imitating them. He displays a unique attitude toward nature and seems to understand its rhythms and textures as a language. Carefully, he makes his way over to the foot of a nearby tree and searches around in the dried fallen leaves for something. It turns out to be a fledgling bird that has fallen from a nest. With great care and determination, the boy manages to pick up the fledgling, then climb up the tree, and locate the nest to which he can restore the little bird. It’s a skilfully edited sequence and reveals something about the way Mohammad relates to the world around him.

Mohammad, an avid student at the school for the blind, learns that the village school that his sisters attend hasn’t yet started its holiday break and begs them to let him go to the school with them. Eventually, this is allowed, and he is given a seat in the class. Fortunately, his braile lessons from the school for the blind match those of the village classroom, and Mohammad turns out to be the star pupil. He comes home thrilled to announce that he received a perfect score at school. This news, however, only irritates Mohammad’s father, since he still believes that the boy has no future in the village.

Fearing his bride-to-be’s family will learn of Mohammad, Hashem takes Mohammad away and leaves him with a blind carpenter who agrees to make him an apprentice. The blind carpenter begins to mentor the boy, but Mohammad begins to cry and expresses that he wants to see God. Mohammad says that God must not love him for making him blind, and says that his teacher taught that God loves the blind children more for their blindness. Mohammad then questions why God should make him blind if he truly loves him more. He also says that he wanted to be able to see God, and that his teacher said that God is everywhere and one can also feel God. The carpenter simply remarks that he agrees and walks away, possibly affected by the boy’s words as he himself is blind.

Mohammad’s grandmother is heartbroken when she realizes that Hashem has sent Mohammad away to apprentice under a blind carpenter, and, in her distress, she falls ill. She leaves the family home, but Hashem tries to convince her to stay, questioning his destiny, and lamenting his deceased wife and blind son. As she leaves, Mohammad’s grandmother drops a hairpin from Mohammad into a pond and faints, falling into the water as she attempts to find it again. Hashem carries her back home. Eventually, Mohammad’s grandmother dies. Hashem receives yet another crushing setback. The family of the girl he wishes to marry has decided to cancel the upcoming marriage because of “bad omens”. So he goes to the carpenter and decides to bring Mohammad back home with him. While crossing a rickey bridge on the way home, the bridge collapses, and Mohammad falls into the swift stream and is rapidly swept down river. For a moment, Hashem stands petrified, looking on in shock at the sight of his son being dragged away; he appears to be torn between rescuing him and freeing himself of his “burden.” Moments later, he makes his decision, dashes into the river, and is also carried along swiftly by the roaring water, behind Mohammad. But the swirling waters are too rough for him to do anything but try to say afloat. He is eventually deposited, unconscious, on the more calm banks of the river mouth into the Caspian. When he regains consciousness, he looks about him and sees the figure of Mohammad some distance away, lying on the shore. Hashem wakes up on the shore of the Caspian Sea and sees Mohammad lying motionless a short distance away. He drags himself up and stumbles toward Mohammad’s body and takes him in his arms. Hashem weeps over his son’s body and looks to the skies. He has lost something precious. A woodpecker is heard, and the sun comes out; Mohammad’s fingers slowly start to move. Perhaps he is “reading” the sound with his fingers as if they are Braille dots, or maybe, in his death, he has finally touched God.

In this film Majidi again demonstrates his ability to express in cinematic terms some of the deep stirrings we have about life. The relationship between a young boy and his father plays a significant role in the narrative. The father, though, is not a bad person, and we can feel for him, too. For him, life is a constant struggle, and he sees himself as a victim in a hostile world. At times when he travels alone, he apprehensively hears the noise of some wild animals, perhaps wolves, barking in the distance. The indistinct, threatening nature of this noise represent the unknown, the “evil eye”, which is lurking in the darkness, just around the corner. Worried about his son’s future, and his own, the father decides to see if he can apprentice the boy to a blind carpenter in a neighbouring village. He reasons that the carpenter can tutor the boy so that he can be able to earn a living.

Rushing over, he discovers that the boy is dead, and he weeps uncontrollably, with the boy in his arms. A flock of wild birds flies overhead, as the mystery of life for others goes on. In the final shot, the camera moves in from above to a close-up of Mohammad’s hand, showing the fingertips illuminated in the same eerie light shown at Aziz’s death, and moving slightly. Mohammad, too, has now joined God and is finally “seeing” Him with his fingers.

This is a religious film, but not one with the conventional religious answers. None of the living people in the film gains enlightenment – in this world, anyway. Hashem, perhaps, now realises the treasure he has lost. Both Mohammad and Aziz were the ones who naively engaged the world in this way, and perhaps they were the ones who gained the most, even in this earthly world. Mohammad had spent his time trying to “read” the stones on the beach, as if they were coded in braile. When we reflect on the hopeless absurdity of his effort, we are reminded that we, ourselves, are equally blind in our own attempts to read meaning in the world by means of our tools and power of analysis.

Much of what makes The Color of Paradise effective as a film are the pastoral scenes of Mohammad trying to discover the wonders of the world around him. These are contrasted with Hashem’s struggles as a builder, carrying out routine, repetitive, and strenuous tasks that have been set up in the more restricted world of economic society and that he must complete in order to earn his keep. The cinematography throughout the film is superb, and the filming of the collapsing bridge scene is particularly remarkable. The acting in the film is remarkable, too, since only the role of Hashem was filled by a professional actor, Hossein Mahjoub.

Director’s work feels truly intended for God’s glory, unlike so much “religious art” that is intended merely to propagandize for one view of God over another. His film looks up, not sideways. In this and his previous film, the luminous Oscar nominee “Children of Heaven,” he provides a quiet rebuke to the materialist consumerism in Western films about children.

The Color of Paradise” was shown as part of last year’s New York Film Festival with the title “The Color of Heaven.” Following are excerpts from Stephen Holden’s review, which appeared in The New York Times on Sept. 25, 1999. In one way or another, the cinema of every nationality addresses the tenuous relationship of man and nature. But in Iran this grandest of themes is almost a national obsession. And in Majid Majidi’s stunningly beautiful film, “The Color of Heaven,” that relationship is evoked with an ecstatic sensuousness along with an awed awareness of nature’s destructive power that are nothing less than extraordinary. Moving through fields of flowers and misty forests, across streams and into the craggy backwoods country, the film makes sure that we hear as well as see the rugged Iranian landscape in all sorts of weather. The soundtrack is a constantly shifting chorus of birds, insects, wind and rain. This soundtrack is especially significant because the movie focuses on the uncertain fate of a blind 8-year-old boy, Mohammad, whose widowed father balks at caring for him. While the movie makes us continually aware of the sounds Mohammad hears, it also shows us the beauty he is unable to see.

Photo courtesy Google. Experts taken from Google.