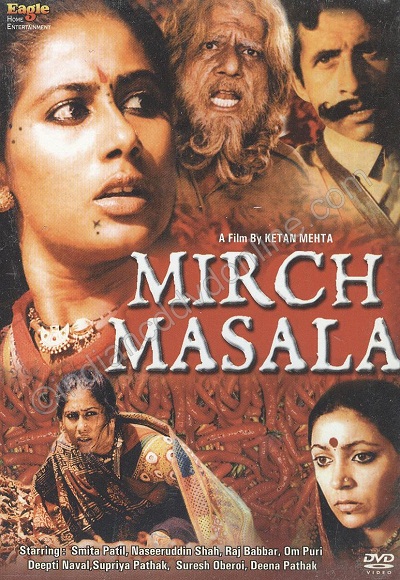

Mirch Masala (Hot Spice) is a 1987 Hindi thriller film directed by Ketan Mehta.

In the early 1940s, an arrogant Subedar (Naseeruddin Shah) (local tax collector in colonial India) and his henchmen ride into a village, scaring a group of women fetching water. Sonbai (Smita Patil) alone stands her ground and politely asks them not to let horses into the village’s potable water source.

Subedar settles into his camp and the Mukhi (the chieftain) of the village visits him to pay respect. Subedar’s gramophone is an object of fascination for the men of the village. Mukhi’s frequent absence from home is resented by his wife. The schoolmaster (Benjamin Gilani), tries to get her to enrol her only daughter in the school. When she does, other women ridicule her. Mukhi pulls his daughter out and beats his wife for disobeying him. While the men of the film are given status, the women are given identity. The lovely Supriya Pathak plays Radha, who, in spite of her father’s beatings, dares to romance above status. The mukhi’s younger brother (Mohan Gokhale) is in love with Radha, but dares not mention it. When their liaison is found out, the girl’s father beats her and tries get the mukhi to agree to a marriage. The mukhi rejects the proposal as unsuitable.

The subedar’s men routinely loot the village for food, livestock and supplies. When mukhi brings a woman to him, he is disappointed that she is not Sonbai. He persists in wooing Sonbai, but when his demands turn forceful, she slaps him across the face. The moment takes the wind out of the subedar’s sails, but Sonbai recovers first, realising she has set danger afoot and runs away. He wants to have his way with her, but she humiliates him, runs and takes shelter masala karkhana (spice factory where red chillies are ground into powder). Abu Mian (Om Puri), the wizened old Muslim gatekeeper and factory guard shuts the factory doors keeping the soldiers out. The subedar attempts to get the gates open through the factory owner and the mukhi fail. Abu Mian refuses to compromise on his job of providing security to the factory employees. This angers the Subhedar, and he asks the town Mukhiya, to get Sonbai to him, or else he will destroy his town. The terrified Mukhiya and the rest of the townspeople decide to turn over Sonbai to the Subhedar, so that he can leave them in one piece, on the condition that they do not molest any more women. The Subhedhar is angered at this show of defiance, and refuses to agree to any conditions. The villagers and the Mukhiya must now decide whether to hand over Sonhai to him, or let him get her and destroy their village, and molest their wives, daughters, and sisters.

Subedar’s threats of destroying the village prompt the mukhi to convene the village panchayat. The villagers hold Sonbai responsible for inciting the subedar and decide that she should yield to him. The schoolmaster points out that once they give in for one, there will be nothing to stop the subedar from demanding others, even perhaps the mukhi‘s own wife. Mukhi thrashes him and throws him out. Mukhi reports back to the subedar that they will hand over Sonbai on the condition that the subedar will not make further demands of this nature. The subedar laughs off this condition and has the schoolmaster tied up to a post.

The mukhi brings pressure on Sonbai, but she stands firm. Within the factory, the women who once supported Sonbai now turn upon her. They fear that if she does not yield, the subedar may send his men to indiscriminately molest the womenfolk. Sonbai nearly relents, but is stopped by Abu Mian. She resolves to stand firm. Abu Mian chides the mukhi and the villagers; they may lord it over their wives at home, but are not man enough to face the subedar.

The subedar orders his soldiers to charge the factory, and they smash down the door. Abu Mian manages to shoot one of the soldiers, but he is shot dead immediately after. The subedar enters the factory and tries to grab Sonbai. The women of the factory mount a sudden and surprising defense. They attack the subedar with bagfuls of lal mirch masala (fresh ground red chilli powder) in teams of two. The film ends with the subedar on his knees, screaming in pain as the chilli burns his face and eyes.

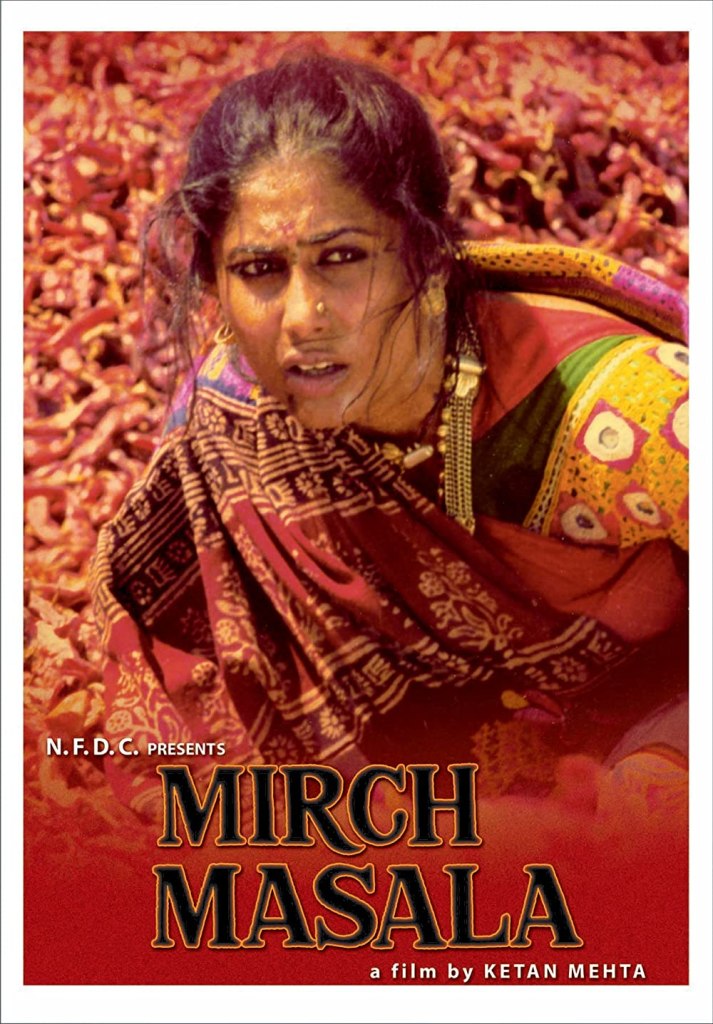

Intercut with shots of their noisy pursuit are striking pictures of Sonbai in flight. Hair askew, the wind snatching at her garments, she is a barefooted, wild creature desperately seeking a haven. Somewhat camouflaged in the colours of her clothes, Sonbai darts and dodges behind pyramids of red chillies roasting on the burning land. Breathless, she finally bursts into the masala karkhana, where women of her kind work in safety. Rajat Dholakia’s music is dramatic and the urgency of action is spectacularly captured by Jehangir Choudhary’s camera.

Sonbai’s counterpart is played by Deepti Naval. Naval competently plays against type. Deepti Naval’s character is confined to a life behind walls and windows. Her valiant attempts to break out of a stifled existence is what makes her worthy of admiration. At first, see her as the dutiful but distracted wife of the macho Mukhi (Suresh Oberoi), who rejects her bed. She takes a stand, locking him out of their house and saying she will let him enter only when he learns to treat it like a home. As a woman who is somewhat educated (she is named after Saraswati, the goddess of learning) and inspired by the masterji of the village, she now dares to challenge the established order and takes her young daughter to school. This initiative has violent consequences. Her husband storms into the school, scoops up his daughter and returning home, flings the child into his wife’s arms. Another act of disobedience, he threatens, and he will break his wife’s legs. He is almost as bad as his word. When the fearless Saraswati tries to summon up a sisterhood of solidarity for Sonbai, he drags his wife by her hair, pulls her into their verandah, and after a few resounding slaps, locks her indoors, setting an example for others whose wives had had the temerity to join Saraswati in her mission. The audience’s last view of Saraswati shows her tearlessly battering against the cement grilled prison she still has to call home.

Sonbai racing past a bush of wild, prickly cactus plants is a powerful scene highlighting its throbbing mood and thrilling tension. In the final sequence, a crowd of emasculated men stare open-mouthed as the harrumphing subedar breaks into the chilli factory. With menacing chuckles, he advances towards Sonbai, for whom he has lusted all along. Sonbai looks at him squarely, her hand reaching for a sickle. Suddenly and utterly united, the women of the factory rush towards the predator, blinding him with fiery red chilli powder. The unwitting catalyst of an uprising long overdue, Sonbai stands swathed in red fumes. She is now the triumphant mascot of oppressed women who have won their day.

The film carefully highlights the notion how men must protect ‘their’ women, and protecting women is a sign of ‘masculinity’. A villager comments how men who decide to give away Sonbai probably wore bangles. Eventually, the same bangle-ghaghara-choli-clad women cause the end of the cruel Subedar. Chowkidar Abu Miya also says how he’s the only man in the village for he is the only one protecting these women and questions if there is no other ‘man’ around. Beimaan hone se namak haraam hona behtar hai.’ Abu Miya’s virtue and bravado embodies the wall that stands between right and wrong. And Puri’s magnificent portrayal goes well beyond the good Muslim stereotype.

The idea of a convenient religion is also portrayed interestingly when the Pandit tries to convince Sonbai to go to the Subedar saying that sex and pleasure are just ‘moh-maaya’. The same Pandit would’ve otherwise said sex is sinful and even if it is just in one dialogue, the hypocrisy of religion comes out beautifully.

The actions of two women at two ends of the economic and social spectrum speak for all women in between. The women are real, with real struggles, passions, and pleasures. Even while being held hostage, they find pleasure by playing with chilli and laugh their way through it. In its bright red hue, the best takeaway from Mirch Masala in these extremely cynical times would be that problems are not the only feminine reality, we also know pleasure, strength and hope. Mirch Masala gets it right in so many ways with its clarity of the differences of experience of women of different social locations.

Mehta’s realistic rural ambiance contributes to Mirch Masala‘s lasting charm. And Chowdhury’s amber-toned portrait of Sonbai in her domestic space is a dazzling case in point. Spice, substance, Smita Patil: A a picture is truly worth a thousand words. Realistic rural ambiance contributes to Mirch Masala‘s lasting charm. And Chowdhury’s amber-toned portrait of Sonbai in her domestic space is a dazzling case in point. Horse riding men treading on and trampling about a field of delicate looking chilli — there’s something telling about Mirch Masala‘s opening frame in how it depicts the authority and susceptibility. Sonbai racing past a bush of wild, prickly cactus plants is a powerful scene highlighting its throbbing mood and thrilling tension. On the centenary of Indian cinema in April 2013, Forbes included Smita Patil’s performance in the film on its list, “25 Greatest Acting Performances of Indian Cinema”.

Spun in rustic earthy colours, ground in folklore and pounded with melodrama, Mirch Masala is a tale of spiced vengeance. Golden rays of Gujarat’s morning sun welcoming the women workers at the gate of the masala factory, it’s an affectionately shot visual of a site oblivious to the bloody action it will witness a few hours later. Chowdhury’s wizardry in moody portraits is a joy to behold. And when Smita Patil and her haunting eyes play muse, the upshot is breathtakingly good. The lovely Supriya Pathak has a minor but integral part to play. Her impulses — in romance and rebellion — are the high points of Mirch Masala. A steely Deepti Naval leading a small-scale protest of neighbourhood ladies, as they clang plates and spoons to voice their anger over Sonbai’s harassment makes for a profound statement in Mirch Masala.

Mirch Masala was one of Mehta’s notable efforts, and won him the Best Film Award at Hawaii. 15th Moscow International Film Festival film Nominated Golden Prize.

Photo courtesy Google. Experts taken from Google..