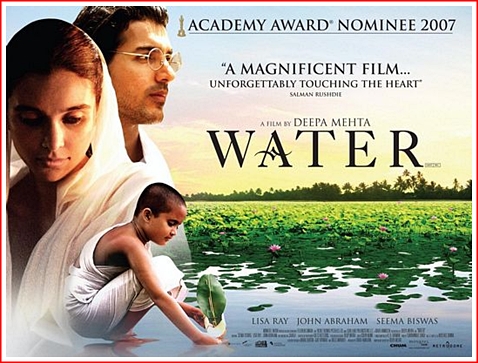

Water is a film written and directed by Deepa Mehta, with screenplay by Anurag Kashyap. It is set in 1938 and explores the lives of widows at an ashram in Varanasi, India.

In the film, Chuyia (Sarala), an adorable eight-year-old, has just been widowed. Her marriage, which she doesn’t even remember, was arranged by her family for financial reasons. But no matter what her circumstances, Hindu law says she must now leave society, and so her parents take her to a decrepit ashram where widows of all ages live together. The little girl’s hair is clipped, and she is dressed in a white robe. She sleeps on a thin mat in a room with older and infirm women whose lonely lives have been spent in renunciation. They sing religious hymns every day.

But the feisty, precocious, disbelieving Chuyia (Sarala) soon turns the house upside down with her rebellious spark. She begins to have a profound affect on the other women who live there, in particular the devout Shakuntala (Seema Biswas) and the beautiful Kalyani (Lisa Ray) who has been forced into prostitution by the domineering head widow, Madhumati (Manorama).

Shakuntala is perhaps the most enigmatic of the women. Attractive, witty and sharp, she is also one of the few widows who can read. She exudes enough anger that even Madhumati leaves her alone. Shakuntala is caught between being a God-fearing, devout Hindu, and her hatred of being a widow. She seeks the counsel of Sadananda (Kulbhushan Kharbanda), a priest, who makes her aware of her unjust and unholy situation. She becomes attached to Chuyia upon her arrival at the ashram.

Chuyia is convinced that her stay is a temporary one and that her mother will come to take her away but quickly adapts to her new life. She befriends Kalyani, and witnesses Kalyani’s budding romance with Narayan (John Abraham), a charming upper-class follower of Mahatma Gandhi. Despite her initial reluctance, Kalyani eventually buys into his dream of marriage and a new life in Calcutta. She agrees to go away with him.

Her plan is disrupted when Chuyia accidentally reveals their affair to Madhumati. Enraged at losing a source of income and afraid of the social disgrace, Madhumati locks Kalyani up. Much to everyone’s surprise, the God-fearing Shakuntala lets Kalyani out to go meet Narayan, who ferries her across the river to take her to his home. However, when Kalyani recognizes Narayan’s bungalow, she realizes that Narayan is the son of one of the men whom she has been pimped out to. In shock, she demands that he take her back. Narayan confronts his father, learning the reason for Kalyani’s actions. Disgusted, he decides to walk out on his father and join Mahatma Gandhi. He arrives at the ashram to take Kalyani with him, only to find that Kalyani has drowned herself.

Madhumati sends Chuyia away to be prostituted as a replacement for Kalyani. Shakuntala finds out and tries to prevent the worst, but she is too late. When Shakuntala finds Chuyia, Chuyia is deeply traumatized and catatonic. Cradling Chuyia, Shakuntala spends the night on the shores of the river. Walking through town with Chuyia in her arms, she hears talk of Gandhi speaking at the train station, ready to leave town. She follows the crowd to receive his blessing. As the train departs, in an act of desperation Shakuntala runs alongside the train, asking people to take Chuyia with them. She spots Narayan on the train and hands Chuyia over to him. The train departs, carrying Chuyia away while leaving the teary-eyed Shakuntala behind.

“Water” is the third film in a trilogy about India by Deepha Mehta. She is not popular with Indian religious conservatives, and indeed after the sets for “Water” were destroyed and her life threatened, she had to move the entire production to Sri Lanka. That she is a woman and deals with political and religious controversy makes her a marked woman.

The film is set in 1938 during India’s road to independence with the film examining the plight of impoverished widows at a temple in Varanasi, India.

Child marriages (to older men) was still prevelant during the colonial rule of the British Raj in India. When a husband died, his wife would be forced to spend the rest of her life in an ashram, an institution for widows to make amends for the sins of her previous life that supposedly caused her husband’s death.

Chuyia an eight-year-old widow who has just lost her husband, paves the way for many changes in the lives of the once discarded and improverished widows inhabiting the ashram. The entire film had been her story. But Chuyia meets Narayan, a tall, handsome, foreign-educated follower of Gandhi, and when she brings him together with Kalyani, they fall in love. This does not lead to life happily ever after, but it does set up an ending as melodramatic as it is (sort of) victorious. We’re less interested in Kalyani’s romantic prospects, however, than with Shakuntala’s logical questioning of the underpinnings of her society.

The film sees poverty and deprivation as a condition of life, not an exception to it, and finds beauty in the souls of its characters. The unspoken subtext of “Water” is that an ancient religious law has been put to the service of family economy, greed and a general feeling that women can be thrown away. The widows in this film are treated as if they have no useful lives apart from their husbands. They are given life sentences. They are not so very different from the Irish girls who, having offended someone’s ideas of proper behavior, were locked up in the church-run “Magdalen laundries” for the rest of their lives.

Water is a co-production between Canada, India and the United States. The film was shot twice with the same (bilingual) actors, once in Hindi, once in English.

The film debuted on 8 September 2005 at the Toronto International Film Festival and opened in other theatres at the dates given below. After several controversies surrounding the film in India, the Indian censor boards cleared the film with a “U” certificate. It was released in India on 9 March 2007.

The film received high praise from Kevin Thomas, writing in the Los Angeles Times : For all her impassioned commitment as a filmmaker, Mehta never preaches but instead tells a story of intertwining strands in a wholly compelling manner. “Water,” set in the British colonial India of 1938, is as beautiful as it is harrowing, its idyllic setting beside the sacred Ganges River contrasting with the widows’ oppressive existence as outcasts. The film seethes with anger over their plight yet never judges, and possesses a lyrical, poetical quality. Just like the Ganges, life goes on flowing, no matter what. Mehta sees her people in the round, entrapped and blinded by a cruel and outmoded custom dictated by ancient religious texts but sustained more often by a family’s desire to relieve itself of the economic burden of supporting widows. As a result, she is able to inject considerable humor in her stunningly perceptive and beautifully structured narrative. “Water” emerges as a film of extraordinary richness and complexity.

Noted Author Salman Rushdie, no stranger to controversy and extremist fury himself, has noted about Deepah Mehta’s “Water” that “The film has serious, challenging things to say about the crushing of women by atrophied religious and social dogmas, but, to its great credit, it tells its story from inside its characters, rounding out the human drama of their lives, and unforgettably touching the heart.”

In an interview, Deepa Mehta stated: “Water can flow or water can be stagnant. I set the film in the 1930s but the people in the film live their lives as it was prescribed by a religious text more than 2,000 years old. Even today, people follow these texts, which is one reason why there continue to be millions of widows. To me, that is a kind of stagnant water. I think traditions shouldn’t be that rigid. They should flow like the replenishing kind of water.”

Water was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film. Winning Canada’s National Film Awards for Best Actress, (Seema Biswas) ‘Water’ went to on to win the Best Motion Picture award at the Bangkok Film Festival 2006.

Jeannette Catsoulis of The New York Times selected Water as NYT Critics’ Pick, calling it “exquisite”: “Serene on the surface yet roiling underneath, the film neatly parallels the plight of widows under Hindu fundamentalism to that of India under British colonialism.”

Water could easily be a bleak story of deprivation and loss, but in Mehta’s gentle hands, it becomes one charged with hope and optimism. “Water” is a masterpiece. It is a masterpiece of artistry, and it is a masterpiece of humanity. It is a masterpiece of determination, and it is a masterpiece of courage. Deepa Mehta has shared her love for all of humanity. It is called “Water.”

Photos courtesy Google. Experts taken from Google.