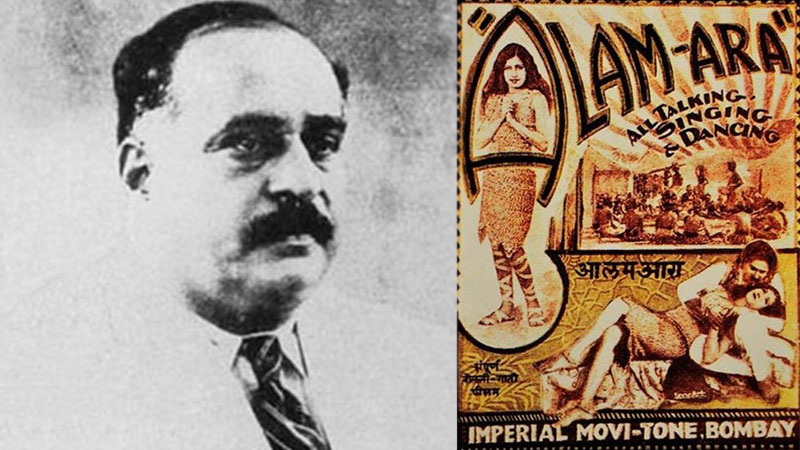

Alam Ara (Ornament of the World) was the first Indian historical fantasy and sound talkie made in 1931 directed by Ardeshir Irani. The film, not only broke the dominance of silent films, which were being made till then, but it also introduced the concept of music and playback in Indian cinema- something that continues to be the highlight of Indian films till date.

After watching Harry A. Pollad’s 1929 American romantic drama part-talkie Show Boat at Excelsior Theatre in Bombay (present-day Mumbai), Ardeshir Irani was inspired to make his next project a sound film which he would direct and produce. Although having no experience creating this type of film, he determined to make it and decided to not follow any precedential sound films. The project was subsequently titled Alam Ara and produced by Irani for Imperial Film Company (IFC), an entertainment studio he co-founded with the tent showman Abdulally Esoofally in 1926. The story was adapted from the Bombay-based dramatist Joseph David’s Parsi play of the same name, while the screenplay was done by Irani. The dialogue was written in Hindustani, a mix of Hindi and Urdu.

The story revolves around the King of Kumarpur and his two wives, Dilbahar and Navbahar, both childless. Soon, a fakir (Muhammad Wazir Khan) tells Navbahaar she will give birth to a boy but she must find a necklace tied around a fish’s neck—which will appear once at the lake of the palace — if she wants her son not to die on his 18th birthday. The boy is named Qamar (Master Vithal). Beside that, Dilbahaar has an affair with the palace’s senapati (Prithviraj Kapoor), Adil. The king finds out about this, and Dilbahaar tells him it was Adil who seduced her first. Therefore, the king arrests him and evicts his pregnant wife, Mehar Nigar, from the palace; Nigar gives birth to Alam Ara (Zubeida) and dies when a shikari tells her about her husband. The shikari later adopts Ara.

Dilbahaar is jealous of Navbahaar and knows about her agreement with the fakir. When the necklace appears on Qamar’s 18th birthday, she secretly replaces it with a fake one, which makes Qamar die. His family, however, does not bury his body and starts looking for the fakir to find what was wrong. As a result, Qamar lives again every night when Dilbahaar removes the necklace from her neck and later dies when she wears it in the morning. Apart from that, Ara knows about her innocent father’s suffering, vowing to release him from jail. On her visits to the place one night, Ara sees the alive Qamar and falls for him. Everyone in the palace subsequently knows about Dilbahaar’s foul play and finally gets the real necklace, with Adil being released. The film ends with Qamar and Alam Ara living happily together.

Zubeida was cast in the title role after Irani’s frequent collaborator. Irani wanted a “more commercially-viable” actor, an opportunity taken by Master Vithal—one of the most successful filmmakers of Indian silent cinema. When Vithal decided to star in the film, he ended his ongoing contract with Saradhi Stidios, at which he started his career, and it made him face legal issues as the studio believed he had a breach of contract. With help from his lawyer Muhammad Ali Jinnah, he won the case and moved to IFC to play the male lead of Alam Ara.

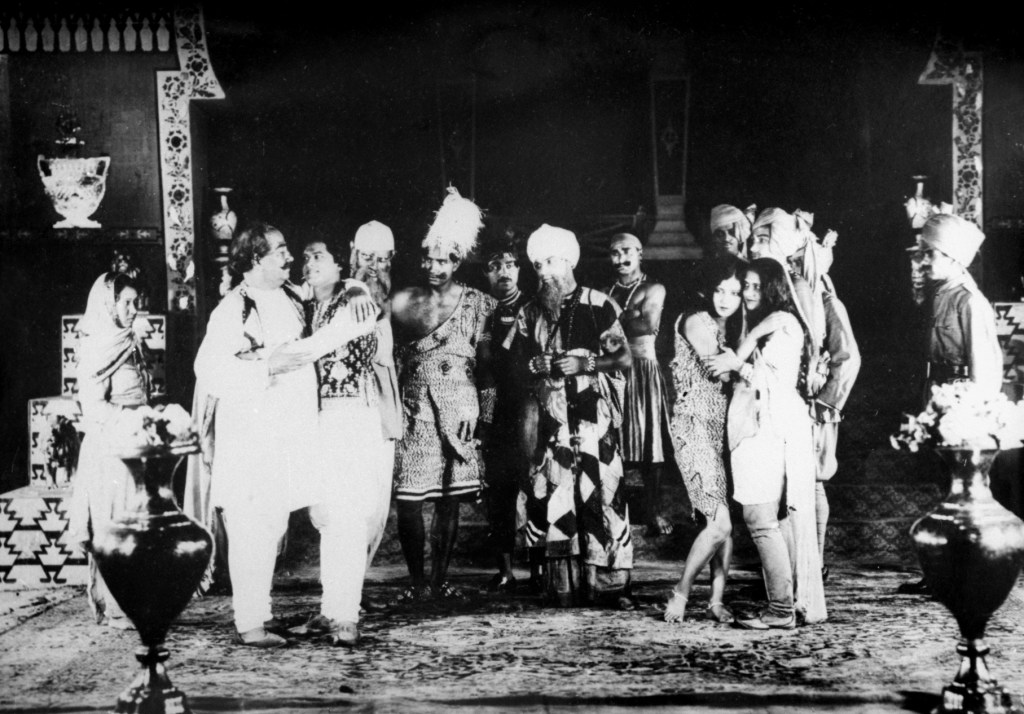

Principal photography was completed by Adi M. Irani at Jyoti Studios in Bombay within four months, using equipment that was bought from Bell & Howell. As the studio was located near a railway track, the film was shot mostly during the nighttime—between 1:00 am and 4:00 am—to avoid noise from the active trains, which according to Ardeshir Irani would pass every several minutes. Microphones were placed at concealed locations around the actors.

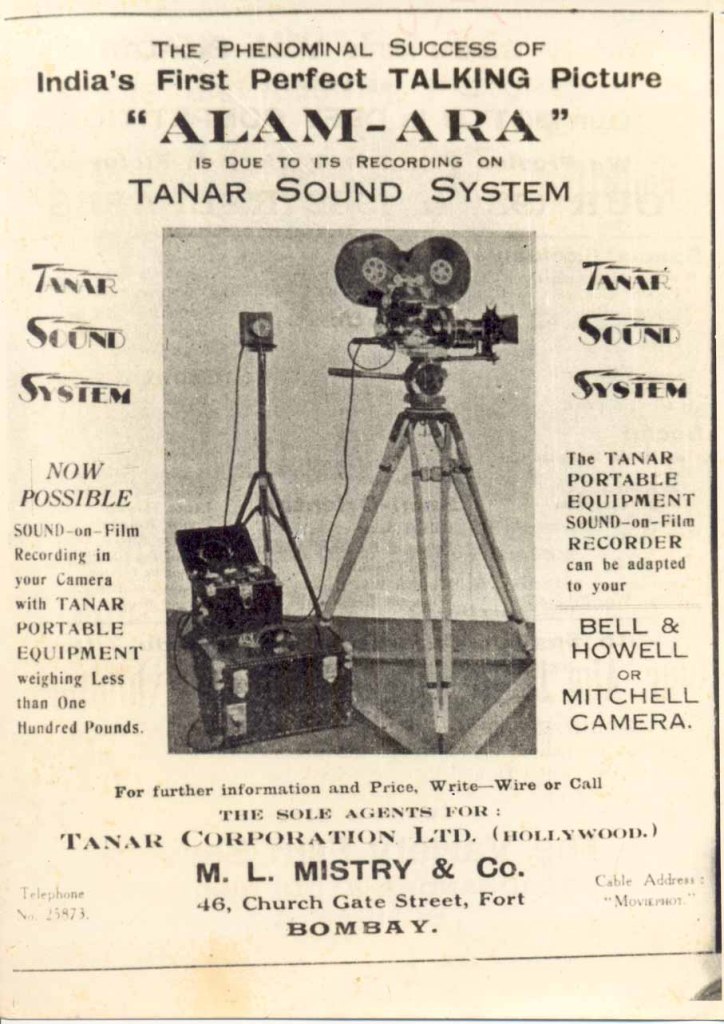

Irani and Rustom Bharucha, a lawyer and the manager of his other production company, Imperial Studios, worked as sound technicians for the film. Ardeshir Irani told an interviewer that he had picked up the basics of sound recording from a “Mr Deming, a foreign expert, who had come to Bombay (now Mumbai) to assemble the machine for us”. Mr Deming charged the producers 100 rupees per day – “a large sum for those days which we could ill afford, so I took upon myself to record the film” with the help of others, he said. Irani could not fulfill his demand and later finished it by himself and Bharucha. They used Tanar, a single-system recording by which sound is recorded at the same time of shooting. Firozshah Mistry and B. Irani served as the music director. After filming ended, Alam Ara was edited by Ezra Mir and its final reel length was 10,500 ft (3,200 m).

The soundtrack to Alam Ara was released by Saregama, and has a total of seven songs: “De De Khuda Ke Naam Pe Pyaare”, “Badla Dilwayega Yaar Ab Tu Sitamgaroon Se”, “Rootha Hai Aasmaan”, “Teri Kateelee Nigaahon Ne Mara”, “De Dil Ko Aaram Aey Saaki Gulfaam”, “Bhar Bhar Ke Jaam Pila Ja”, and “Daras Bin Morey Hain Tarse Nayna Pyare”. “De De Khuda Ke Naam Pe Pyaare”, sung by Muhammad Wazir Khan, became popular at the time of its release and was acknowledged as the first song of Hindi cinema. Zubeida performed mostly the rest of the songs. Since there were no boom mikes to record sound, microphones were placed in “incredible spaces” around actors – who spoke in Urdu and Hindi – in a way that they were hidden from the camera. Musicians climbed on or hid behind trees and played their instruments for the soundtrack and songs. Most importantly, the film featured Wazir Mohammed Khan, playing an ageing mendicant, who sang the first Indian film song.

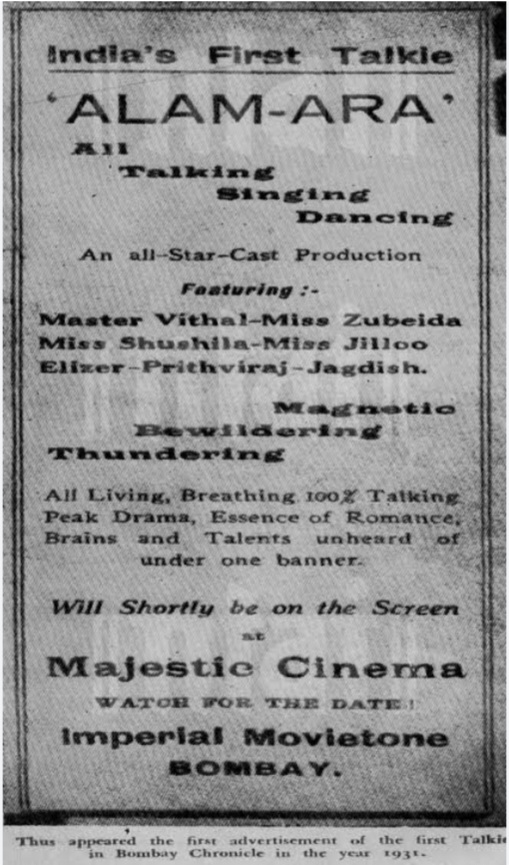

Distributed by Sagar Movietone, Alam Ara premiered at the Majestic Cinema in Bombay on 14 March 1931. It was advertised with the English tagline, ‘All living, Breathing, 100 per cent talking’ and a Hindi punchline, ‘78 murde insaan zinda ho gaye. Unko bolte dekho?’ The movie had become such a hit that police had to be called to control the crowd. The film was houseful for the next 8 weeks of its release. When the film hit the screens, the joy had reached such a fever pitch that theatres had been mobbed, riots unleashed and tickets meant for 4 annas (about 25 paise) had been bought at Rs 5 — and thus started the black advertising of film tickets. Ramesh Roy, an office boy of IFC, brought the film’s reel to the theatre. When Mayank Shekhar of the Hindustan Times interviewed him in 2006, he recalled it as “a moment in history, when the public coming out of the show wouldn’t stop talking about the film they’d seen, that also talked!” According to Daily Bhaskar, crowds of people would stand in line from 9:00 am although the first show occurred at 3:00 pm. As a solution, police were assigned to the theatre and allowed to use sticks to control the crowds and traffic. Sharmistha Gooptu, in her article published in The Times of India, reported: “Alam Ara is proving to a great attraction at the Majestic Cinema, and crowded houses have been the order of the day.” It was also the first film to be screened at Imperial Cinema in Paharganj.

Critics were appreciative, with the performance and songs got the most attention though some of whom criticised the sound recording. In addition to the successes, the film was also widely considered a major breakthrough for the Indian film industry and Ardeshir Irani’s career with its status as the country’s first sound film.

“The theatre was mobbed. Tickets were unavailable for weeks and the police was called in to control a riotous mob,” writes movie historian B.D. Garga on the discharge of Alam Ara in his e book, Artwork of Cinema.

Writing for The Rough Guide to World Music (1999), Mark Ellingham reported that the film’s success has influenced India, Sri Lanka, and Myanmar. In 2003, the scholar Shoma Chatterji hailed, “With the release of Alam Ara, Indian cinema prove two things—that films could now be made in a regional language that the local viewers could understand; and that songs and music were integral parts of the entire form and structure of the Indian film.”

Alam Ara is widely regarded as the first sound film of India. The film is also considered as a turning point of Ardeshir Irani’s career and gave him a reputation as the “father of Indian talkies”. Google made a doodle to celebrate its 80th release anniversary, featuring Vithal and Zubeida. Writer Renu Saran features the film in the book 101 Hit Films of Indian Cinema (2014). In the same year, a 2015 calendar titled “The Beginnings of Indian Cinema” was released, featuring the poster of its.

No print of Alam Ara is known to have survived, but several stills and posters are available. In 2017, the British Film Institute’s Shruti Narayanswamy declared Alam Ara as the most important lost film of India.

Photo courtesy Google. Experts taken from Google.