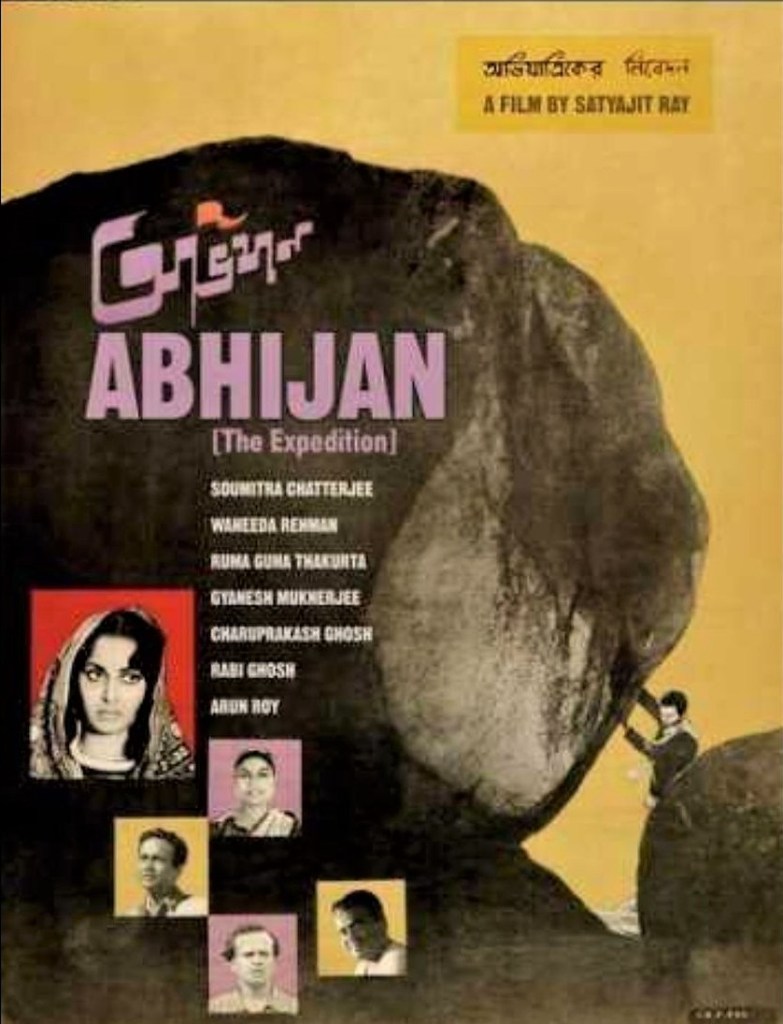

Abhijan (The Expedition) is a 1962 Indian Bengali-language film directed by Satyajit Ray.

The film tells the story of Narsingh, a young Rajput taxi driver living and working in Bengal. Narsingh owns a 1930 Chrysler sedan, which he uses to ferry passengers between two villages. His passion for the car is equalled — and perhaps surpassed — by that of his assistant-cum-handyman Rama, who protects the car with heart, soul and spirit. Narsingh is going through a bad phase in life, as his wife has run away with another man. A Kshatriya by caste, and a descendant of the bloodline of none other than Maharana Pratap himself, he cannot tolerate indignity, insult or defeat of any kind. To add to his woes, an impulsive bout of rash driving has left him in the bad books of the district’s traffic inspector, who has not only cancelled his licence, but thrown him out of his office as well, after insulting him. Disillusioned and dejected, Narsingh decides to return to his hometown in the neighbouring district, but on the way back, he picks up a stranded middle-aged Marwari businessman named Sukharam and his companion — a young woman named Gulabi. When Sukharam offers to help Narsingh set up a taxi service in his village, the Rajput thinks he can find a way to reclaim the lost respect in his life. Little does he know that Sukharam has plans to use his car for smuggling opium, or that the rustic and comely widow Gulabi is being sold by the businessman to the flesh trade. Also appearing in the story is a Christian man named Joseph who used to be a family friend, his young and educated sister Neeli who Narsingh finds himself drawn to, and her crippled lover. In the end, Narsingh finds himself standing at the crossroads, where a single decision can lead him either to a life of dignity, or to one of prosperity.

Ray’s favorite actor Soumitra Chatterjee plays Narsingh, a taxi driver. Narsingh is a proud and hot-tempered Rajput with a passion for his car, a vintage 1930 Chrysler. He recklessly passes the car of a powerful, local policeman and has his permit taken away. It forces him to take refuge in a small town on the borders of the states of Bengal and Bihar. He does not want to be the one who falls behind and develops a strong hatred for women and mankind in general. As a result of reckless driving, while overtaking the car which carried the district inspector, his licence is taken from him. He is utterly destroyed by it, since the cab was his life after his wife had left him for good. Deeply affected by the insult and a feeling of rootlessness, he decides to go back to the land of rajput where his true rajput lineage will be respected.

While on an aimless journey, Narsingh is picked up by Sukharam who is a local Marwari businessman with a record of smuggling and human trafficking. Sukhanram, a shady merchant, offers him a handsome fee to transport some merchandise, and soon he finds himself into trafficking in opium. The two main women characters Neeli and Gulabi form a contrast. Narsingh is attracted to Neeli, a reserved Catholic schoolteacher. She has no interest in Narsingh. The other female character is warm, demonstrative and beautiful prostitute Gulabi. Gulabi has an instinctive liking towards Narsingh. He changes, and rescues Gulabi just in time, before she was to be sold to the same lawyer who was a member of the smuggling racket he had thought of joining.

Although Abhijan is one of Ray’s more ‘commercially inclined’ films, there are some aspects of its craft which deserve high critical commendation. For one, Abhijan has perhaps some of the best editing work that is seen in a Satyajit Ray film. The cutting is top-notch, especially in the first half of the film. The setting up of the shots, the blocking, the camerawork — everything pulls you right into the scenes. Consider the iconic opening shot of the film, for instance, where Narsingh and the owner of a local garage are having a drink in a hooch store. The camera stays on the mechanic, dwelling on the pleasure he derives in taking a dig at Narsingh’s bruised pride. In a broken mirror on the wall behind him, we see half of Narsingh’s face — sullen, gloomy and shattered like the mirror itself. He sulks at all of womanhood, curses his own luck, and yet has the guts to refuse an offer of partnership with the opportunistic mechanic. To him, the most important thing, above everything else, is the blood flowing in his veins, and with the two-and-a-half-minute long single shot scene, Ray successfully convinces us of this simple fact, beautifully setting up the mood for the rest of the film.

Gulabi, on the other hand is a melancholy, demonstrative and beautiful village widow. Gulabi, beautifully played, by Waheeda Rehman pleads with Narsingh to save her from an inebriated Sukhanram by letting her stay in his room for the night, the ill-tempered driver barks at her and asks her to ‘go sit in that corner over there’. Gulabi mistakes Narsingh’s misogyny and apathy for his virtues, for here is a man who, for the first time in her life, hasn’t lusted after her. The scene is devastatingly tragic and beautiful at the same time, and Ray handles it with great sensitivity and a deep understanding of a woman’s heart. Gulabi is instinctively drawn to Narsingh. In spite of losing her dignity, she still looks at the bright side of life and has trust that Narsingh is not immoral. She is attracted to him from the beginning.

The film also marks the beginning of Satyajit Ray’s long-term association with actor Rabi Ghosh, who continued to act in several of Ray’s films, including his final one. Ghosh is absolutely spot-on in the role of Narsingh’s handyman Rama, hitting all the right notes with his impeccable comic timing, beautiful expressions and perfect body language that most actors can only dream of mastering. His allegiance to his employer is unshakable, but in a beautiful scene in which Narsingh announces that he has decided to sell the Chrysler, Rama shows, with breathtakingly beautiful flair, that his love for the car, which he has nurtured and cared for with great love and affection over the years, is even greater than his loyalty for his master.

The tension of the good and evil collapses and the old car makes another journey into nothingness but with a halo of light ahead of it, the light of love. The film gives the famous Ray flavour in its composition, flow and dialogues, and use of symbols.

The film was originally conceived by his friends. A producer friend, Bijoy Chatterjee was to direct it. He had persuaded Ray to write the script and help in pre-production of the film. As a friendly gesture Ray agreed to direct the first scene on the first day of the shoot. By end of the day Bijoy Chatterjee and friends had persuaded Ray to direct the complete film. “They lost their nerve,” Ray said. Ray, who is usually associated with gentle and contemplative films, added a fight scene to Abhijan. He later admitted the fight should have been better staged. The filming took place in 114-degrees weather with the actors wearing heavy clothes to simulate winter. So did he want more violence? “Oh, yes,” Ray said. “I’d have very much liked a John Ford-type rough-and-tumble.”

In 1962 film won President’s Silver Medal.

Photos courtesy Google. Experts taken from Google.