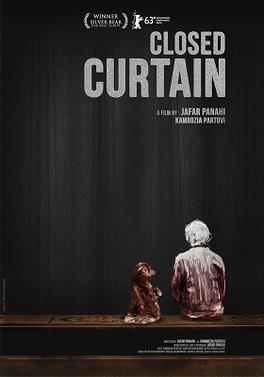

Closed Curtain is a 2013 Iranian docufiction film by Jafar Panahi and Kambuzia Partovi.

An unnamed screenwriter (Kambozia Partovi) arrives at a secluded three-story villa on the Caspian Sea. He secretly brings along his pet dog named “Boy”. Dogs are considered unclean under Islamic rule and the writer intends to hide “Boy” from authorities as he tries to get some writing done. The writer shaves his head to disguise his identity and covers all the windows in the villa with black, opaque material.

One night during a thunderstorm Melika (Maryam Moqadam) and her brother Reza (Hadi Saeedi) break into the villa. They tell the writer that they have fled from an illegal beach party in which alcohol was consumed and are hiding from the police. The writer demands that they leave, but Reza states that his sister is suicidal and then leaves Melika there while he looks for a car.

The presence of Melika begins to unsettle the writer. Melika speaks to the writer cryptically and theatrically, often lying and demanding to know about personal details from the writer’s life. The writer becomes increasingly paranoid and begins to suspect Melika of being a police spy. Melika wants to open the curtains against the writers protests. Melika suddenly vanishes and the writer is left alone. When he hears the back patio door smashed open, the writer and “Boy” hide and listen to the sounds of the house being ransacked by thieves.

The film abruptly changes and becomes more surrealistic when film director Jafar Panahi and other film crew members appear in the villa, with the entire film up to that point having been fictitious. Panahi is seen in everyday situations, such as eating, talking to workers who repair the patio window and interacting with friends. Characters from earlier in the film begin to haunt Panahi, especially Melika. Melika leaves the villa and goes into the water. Panahi follows her there, but the film is suddenly rewound and he finds himself in the villa again. On a cell phone he looks at pictures of filming in the house, showing the writer as he first meets Melika and Reza. At the end of the film Panahi leaves the villa as Melika looks on.

Closed Curtain opens with an extended static shot observed through the metal security bars of a coastal villa’s window. As we’ll discover, this non-to-subtle metaphor for Panahi’s controversial imprisonment is just one of many heavy-handed devices used throughout the film.

A man enters the house and quickly begins to close all the curtains before returning to his packed suitcase. He unzips it to reveal a small dog hidden inside. The reason for this clandestine canine smuggling is because Islamic law forbids the ownership of dogs, as they’re deemed to be ‘unclean’. The man continues to conceal his and his dog’s arrival by blacking out the windows, shaving his hair and building a litter tray for his four-legged companion. However, their elegant hideout loses its peaceful serenity when a man and a woman find their way in. The woman is rather peculiar, but then so too is this incredibly secretive man, leaving to the audience to decipher who or what they are.

Considering the incredible limitations faced by Panahi, it feels harsh to criticise this jarringly self-indulgent drama. Closed Curtain remains engrossing throughout, its contemplative opening and cryptic second act combining subtle expressionism with an exceptionally adorable, film-stealing canine performance. However, the moment Panahi (playing himself) silently enters the fray like an ill-advised cameo, the film’s self-reverential aesthetic tips the scales, turning a heavy-handed, yet enjoyable metaphor for his creative repression into an overblown and jarringly personal odyssey. It’s just all a little too contrived for a director that’s been detained for making subtle political subversive films. Panahi’s follow up is a heartfelt and deeply personal film from a director whose hardships, whilst well-documented, remain incredibly disheartening.

Closed Curtain was announced as being selected to screen in competition of the 63rd Berlin International Film Festival on on Januaryb11, 2013. Festival director Dieter Kosslick is a long time supporter of Panahi and said that he “asked the Iranian government, the president and the culture minister, to allow Jafar Panahi to attend the world premiere of his film at the Berlinale.” The film premiered at the festival on February 12, 2013, where Panahi won the Silver Bear for Best Script.

In response to the Best Script Award Javad Shamaqdari, the head of the Iranian Students News Agency, stated “We have protested to the Berlin Film Festival. Its officials should amend their behavior because in cultural and cinematic exchange, this is not correct” and added “Everyone knows that a license is needed to make films in our country and send them abroad but there are a small number who make films and send them out without a license. This is an offense … but so far the Islamic Republic has been patient with such behavior.” In response to the ISNA’s complaint, the Berlin Film Festival released the statement “We would very much regret if the screening will have any legal consequences for the filmmakers.” On February 28, 2013, Iranian authorities confiscated the passports of Partovi and Moqadam. This prevented them from traveling outside of Iran to promote the film abroad or at film festivals, such as the 37th Hong Kong International Film Festival where it was scheduled to screen on April 2, 2013.

Hanns-Georg Rodek of Die Welt said that the film was “simultaneously a film about courage and cowardice in the repression and simultaneously allegorical and concrete” and that Melika was the “embodiment of free thought”. Deborah Young of The Hollywood Reporter praised the film’s cinematography and lighting despite its low budget and said that the film was “not an easy film to relate to – in fact it deliberately short-circuits any emotional response from the audience– and will have to rely largely on Panahi’s reputation to get off the ground in foreign art venues.” Eric Kohn of IndieWire gave the film an A− rating, but called it “less a finished movie than a cry for help, its enigmatic trajectory allows viewers to empathize with Panahi exclusively through his ideas.”

Photo courtesy Google. Experts taken from Google.