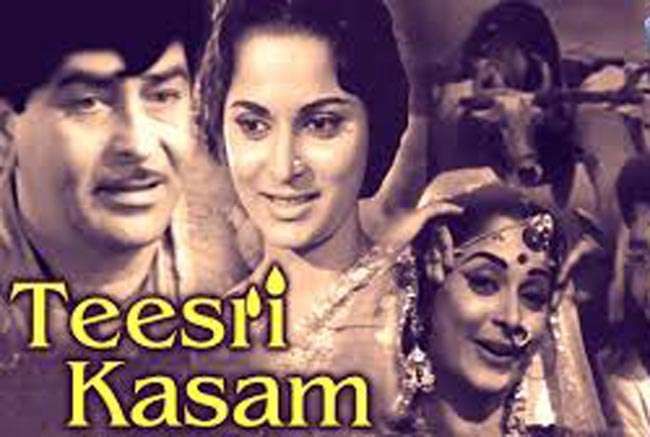

Teesri Kasam (The Third Vow) is a 1966 Hindi language drama film directed by Basu Bhattachrya and produced by lyricist Shailendra. The film is based on Phanishwar Nath’s short story Mare Gaye Gulfam. Shailendra acquired the rights to the story and began filming the film in 1962. The film stars Raj Kapoor and Waheeda Rehman. The duo Shankar – Jaikishan composed the film’s score. The film’s Cinematography was done by Subrata Mitra, dialogues were written by Phanishwarnath Renu and the screenplay is by Nabendu Ghosh.

Hiraman (Raj Kapoor) is a rustic villager, a bullock cart driver, from a remote village. He has traditional and conservative values. While smuggling illegal goods on his bullock cart and narrowly escaping the police, He takes a vow ( pehli kasam) to never again carry illegal goods.

While transporting bamboo for a timber trader, Hiraman’s load upsets the horses of two men. The two men then beat up Hiraman. After this, He takes a second vow (doosri kasam) to never again carry bamboo in his cart.

One night he is asked to carry a woman passenger to a fair forty miles away. She is Hirabai (Waheeda Rehman), a Nautanki performer going to perform at the fair. As they travel together, Hiraman’s innocence and simplicity charm Hirabai who is also moved by the songs he sings to pass the time. Hiraman tells her in song the legend of Mahua, a beautiful motherless girl who fell in love with a stranger but is later sold to a trader by her stepmother. Hirabai coaxes Hiraman to spend a few days at the fair and see her dance. At the Nautanki, Hiraman gets into a fight with a drunkard who makes an insulting comment about Hirabai. Hirabai angrily asks him what right does he have to fight on her behalf. Hurt, Hiraman stays away from the show. Hirabai calls him to her tent and apologises to him. Hiraman asks her to leave this profession where people talk ill of her. His concern touches Hirabai’s heart as she realizes he looks upon her just as is she were a respectable woman.

Becoming unhappy with her situation, she refuses the local zamindar’s overtures. The zamindar tries to force himself on her but she fights him off. Hirabai decides to leave the Nautanki company for her presence will threaten the livelihood of others in the troupe as the zamindar will not leave them alone unless she gives in to him. But she cannot live a lie with Hiraman. She sends for him to say goodbye. At the train station she tells him she is going back to her old company. She tells a hurt Hiraman that like Mahua she already has been sold. As she departs and Hiraman returns to his cart he takes a third vow never to carry a woman from a Nautanki Company again.

It is one of Indian cinema’s tragic ironies that a sensitive and poetic film like Teesri Kasam sank without a trace, indirectly leading to its producer lyricist Shailendra’s death due to stress of financial problems. The irony is even more so as today the film is recognised as one of the all-time great films of Indian cinema. In the climactic sequence, as Hirabai’s train departs and the parting becomes real, Hasrat Jaipuri’s words float over Mitra’s lyrical images of separation — “Sapne jagaa ke tune kahe ko de di judaai, Kahe ko duniya banaayi”

Teesri Kasam is also perhaps director Basu Bhattacharya’s best and most accessible film. He had worked under Bimal Roy earlier and it shows in the film. The rhythm of the film is lyrical and ever so gentle and rarely has rural ethos been captured so beautifully on the Indian screen. The film, refraining from conventional drama, flows like the song of Mahua in the film (Duniya Bananewale) – beautiful, eternal and moving.

The blossoming of the bond between Hiraman and Hirabai through their journey together is warm, wistful and charming and is extremely delicately handled. What draws the nautanki dancer to the rustic cart driver is his simple philosophy of life and his natural aesthetic sense which he expresses through his moving songs. Only as the final parting appears imminent, does the intensity strike. In a key scene of the film Hirabai laments that she could play the part of Laila but could never become Laila herself as she justifies her decision to continue her life as a nautanki performer. Love and Marriage are not for her.

The first time the audience gets a glimpse of Waheeda Rehman in Teesri Kasam, a character on screen exclaims, “Arre, ye to pari hai.” Hiraman, a bullock cart driver played by Raj Kapoor, was actually speaking about his passenger Hirabai. But his exclamation might as well have been a comment on Rehman’s presence in Indian films. ‘A fairy’, as he calls her, is a graceful and powerful metaphor in popular imagination. The basic premise of the story is the bond that Hiraman and Hirabai form during a 30-hour journey in the northern belt and over subsequent days.

The story is the fact that the end of the relationship between Hiraman and Hirabai appears inevitable from the start. To quote Star and Style’s review of the film, “The way the cart driver and nautanki dancer meet, talk and discover each other and themselves at the same time and the manner in which they part are like a poem on celluloid with a thread of pain running through it.”

As Hiraman prepares to go back distraught after his final parting with Hirabai, and is about to hit his bullocks in a fit of anger, he overhears her voice saying, “Don’t hit them!” Earlier, when he was transporting her to the fair and tried to hit the bullocks, she had stopped him with the same words. Now as he looks back, the train in which Hirabai has left in the extreme far background framed through the fluttering curtains of his bullock cart in the foreground. It is an incredible image and brings to the fore beautifully magical cinema can be.

Raj Kapoor and Waheeda Rehman literally live their roles in the film. Raj Kapoor more than compensates with his performance as the naive country bumpkin. Waheeda Rehman responds with perhaps the best performance of her career. The film offers her a great opportunity to showcase both her great histrionic ability and dancing talent and it goes without saying she excels in both. It is a remarkable, perceptive performance.

The film is beautifully shot by Subrata Mitra enhancing the lyrical feel of the film. The frames and compositions are evocative, poetic and rich in tonal quality and represent some of the finest black and white camerawork done in Indian cinema. The lyrics by Shailendra and Hasrat Jaipuri retain the rural ambiance of the film and are simple yet profound.

Rarely does one see a mainstream film where music is so well integrated into the film. Shanker-Jaikishen have given an outstanding musical score in the film – simple melodies rooted in folk music. The music is much enhanced with the use of flutes, traditional string and percussion instruments. Sajanre Jhoot Mat Bolo, Sajanwa Bairi Ho Gaye Hamar, Duniya Bananewale all rendered by Mukesh and Pan Khaye Saiyan Humaro sung by Asha Bhosle stand out. It is interesting to see that in keeping with the realistic and human look of the film, Hiraman is just one of the revellers in the song Chalat Musafir and not the lead singer as is the case normally in our films.

Shailendra the greatest Hindi lyricist of all time produced this film. The film won the National Film Award for Best Feature Film..

Photos courtesy Google. Excerpts taken from Google.