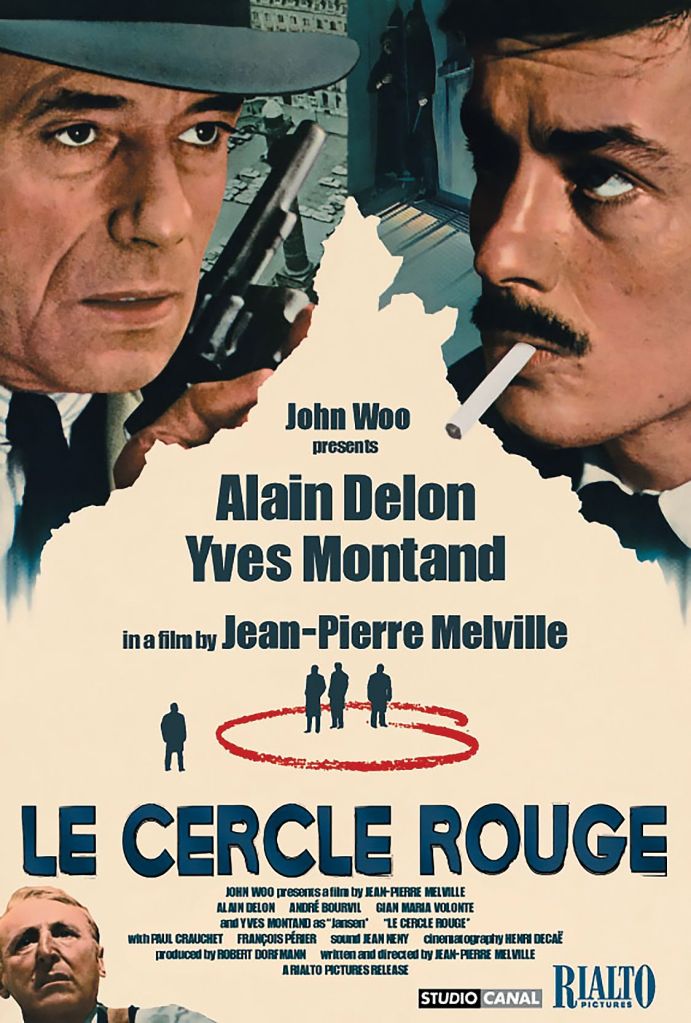

Le Cercle Rouge (“The Red Circle”) is a 1970 crime film set mostly in Paris. It was directed and screenplay by Jean-Pierre Melville and stars Alain Delon, Bourvil, Gian Maria Volonte, Francois Perier and Yves Montand. It is known for its climactic heist sequence which is about half an hour in length and has almost no dialogue. Film based on after leaving prison, master thief Corey crosses paths with a notorious escapee and an alcoholic former policeman. The trio proceed to plot an elaborate heist.

The film opens, in Marseille, a prisoner named Corey (Delon) is released early for good behaviour. Shortly before he leaves, a prison warden tips him off about a prestigious jewellery shop that he could rob in Paris. Corey goes to the house of Rico, a former associate who has let him down and with whom his former girlfriend now lives, and forcefully removes money and a handgun from Rico’s safe. Then he goes to a billiard hall, where two of Rico’s men find him. After killing one, knocking the other out and taking his gun, Corey buys a large American car and, hiding both handguns in the boot, starts for Paris. On the way up, listening to jazz and news on the radio, he encounters a police roadblock.

The same morning another prisoner, Vogel (Volonte), who was being taken on a train from Marseille to Paris for interrogation by the well-respected Commissaire Mattei (Andre Bourvil), manages to escape in open country. Vogel is pursued by and eludes Mattei, who orders roadblocks to be set and supervises the manhunt. Meanwhile, Corey, who has understood what this huge police activity is about, stops at a roadside grill in the epicentre of the manhunt, leaving his car boot unlocked. Vogel crosses a stream to send dogs off his scent, reaches the grill, and hides in the boot of Corey’s car.

Corey, who has seen him and had been waiting for this, drives off into an open field and tells Vogel he can get out because he is safe. After a tense confrontation where Vogel waves one of Corey’s guns, he realizes that Corey has just been released from prison that morning and is trying to save him. The two drive off with Vogel back in the boot. Shortly after, a car with two of Rico’s men catches up and forces Corey off the road. They take him into the woods, take his money, and are about to kill him when Vogel, emerging from the boot with the guns, shoots both dead.

Corey takes Vogel to his empty flat in Paris where they start to plan the aforementioned robbery. For this they need a marksman to disable the security system by a single rifle shot and a fence to buy the goods. Meanwhile, Mattei is trying to locate the murderer of Rico’s men and still trying to recapture Vogel. To do this, he puts pressure on Santi, a nightclub owner who knows most of the underworld, but who refuses to talk.

Corey recruits Jansen, an alcoholic ex-policeman and a crack shot, together with a fence. One long night, Corey, with Vogel and the support of Jansen, successfully rob the jewellery shop. However, the fence refuses to take the goods, having been warned off by a vengeful Rico, who had been told inadvertently by the prison warden from the beginning that Corey was on the job.

Overcoming their disappointment, Jansen and Vogel suggest that Corey ask Santi to recommend a new fence. Mattei blackmails Santi to obtain information about the meeting planned that evening at his nightclub, where Corey is supposed to meet the fence. Mattei, posing as the fence, asks Corey to bring the goods to a country house.

Corey does so, taking Jansen as backup and leaving Vogel at his apartment, who has been given the red rose that Corey had received from the flower girl at Santi’s. After Corey arrives at the country house and starts showing the jewels to Mattei, Vogel appears from nowhere, presumably acting on his suspicion that Corey was not safe with this new fence, and tells Corey to run with the loot. After a brief, tense confrontation with Mattei, Vogel follows Corey. Jansen, alerted by the gunshots in the mansion’s park now filled with police, arrives to stop the pursuants. One after the other, the three men are shot dead by Mattei’s officers, who recover the jewels.

There is one cool, scene the police commissioner talks to the nightclub owner after he knows that the owner’s son, picked up in an attempt to pressure the owner, has killed himself. Jansen, the Yves Montand character, comes into the plot, and think for a moment about why he doesn’t want his share of the loot.

“Le Cercle Rouge” assumes that the crooks will be skillful at the heist, because they are good workmen. The movie is not about their jobs but about their natures.

Melville fought for the French Resistance during the war. Manohla Dargis of the Los Angeles Times, in a review of uncanny and poetic perception, writes: “It may sound far-fetched, but I wonder if his obsessive return to the same themes didn’t have something to do with a desire to restore France’s own lost honor.” The heroes of his films may win or lose, may be crooks or cops, but they are not rats.

Gliding almost without speech down the dawn streets of a wet Paris winter, these men in trench coats and fedoras perform a ballet of crime, hoping to win and fearing to die. Some are cops and some are robbers. To smoke for them is as natural as breathing. They use guns, lies, clout, greed and nerve with the skill of a magician who no longer even thinks about the cards. They share a code of honor which is not about what side of the law they are on, but about how a man must behave to win the respect of those few others who understand the code.

Jean-Pierre Melville watches them with the eye of a concerned god, in his 1970 film “Le Cercle Rouge.” His movie involves an escaped prisoner, a diamond heist, a police manhunt and mob vengeance, but it treats these elements as the magician treats his cards; the cards are insignificant, except as the medium through which he demonstrates his skills.

Melville grew up living and breathing movies, and his films show more experience of the screen than of life. “Le Cercle Rouge,” or “The Red Circle,” refers to a saying of the Buddha that men who are destined to meet will eventually meet, no matter what. Melville made up this saying, but no matter; his characters operate according to theories of behavior, so that a government minister believes all men, without exception, are bad. And a crooked nightclub owner refuses to be a police informer because it is simply not in his nature to inform.

The movie stars two of the top French stars of the time, Alain Delon and Yves Montand, as well as Gian Maria Volonte, looking younger here than in the spaghetti Westerns, and with hair. All of the actors seem directed to be cool and dispassionate, to guard their feelings, to keep their words to themselves, to realize that among men of experience almost everything can go without saying.

Corey, is a thief, but not a killer. Corey is now out for revenge. In the scene, he visits his old boss in his luxury apartment, Melville shows Corey coming out of the elevator, hands in pockets, looking for all the world like an assassin, a cool killer in a trench coat. He is a dignified man, conscious of the proprieties of society. Corey’s flaw, it seems, is the simple fact that he is a thief.

With its honorable antiheroes, coolly atmospheric cinematography, and breathtaking set pieces, film is the quintessential film by Jean-Pierre Melville—the master of ambiguous, introspective crime cinema.

It was the fifth most popular film of the year in France. The film has a 96% rating at film review website Rotten Tomatoes from 69 reviews, with the critics’ consensus stating: “Melville is at the top of his game, giving us his next-to-last entry into the world of deception, crime, and extreme suspense that made him a maestro of the French heist genre.”

Photos courtesy Google. Excerpts taken from Google.