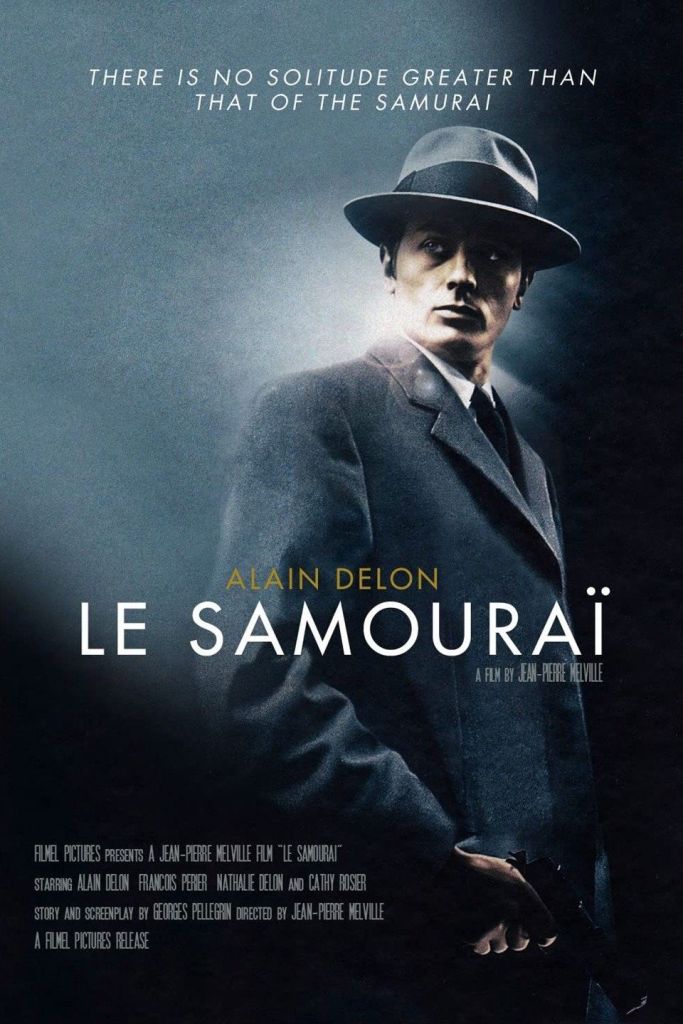

Le Samouraï (1967) is a neo-noir crime thriller directed by Jean-Pierre Melville and features Alain Delon in the lead role, supported by François Périer, Nathalie Delon, and Cathy Rosier.

Set in Paris, the film follows Jef Costello (played by Delon), a meticulous and solitary hitman. After completing a contract killing, Jef finds himself betrayed by his employers and becomes the target of both his former clients and the police, led by a determined commissioner (Périer). The film explores themes of loyalty, isolation, and moral ambiguity, with its minimalist aesthetic and detached tone contributing to its iconic status in the crime thriller genre. The film’s plot revolves around Jef’s efficient but solitary life, his carefully crafted alibis, and the betrayal he faces after carrying out a contract killing.

As the story unfolds, Jef is identified by the nightclub pianist, Valérie, but she chooses not to reveal his identity. This act of discretion raises suspicion, especially since Jef’s unknown employers attempt to kill him instead of paying him for the hit. His interactions with both Valérie and the police commissioner (the commissaire) illustrate the cat-and-mouse dynamic of the film, where Jef is both the hunter and the hunted. The police surveillance, the symbolic small bird in his apartment, and his ultimate decision to return to the nightclub despite the looming threat contribute to the film’s noir themes of alienation and inevitability.

The climax occurs when Jef, prepared for his own downfall, approaches Valérie in full view of witnesses and police. He makes no effort to hide his identity, and although he points his gun at Valérie, his weapon is revealed to be unloaded after he is fatally shot by the police. This ending encapsulates the film’s philosophical undertones, with Jef’s actions reflecting a resigned sense of fatalism, ultimately leading to a self-imposed end.

Review of Le Samouraï highlights Jean-Pierre Melville’s mastery in using minimalism to create suspense and a haunting atmosphere. The film’s opening scene, Jef Costello lighting a cigarette in a sparse apartment, immediately draws the viewer into a cold, detached world. Without speaking, Melville conveys mood and character through light, shadow, and deliberate movements, underscoring Jef’s methodical nature.

Jef is a hitman who lives by a rigid, almost samurai-like code of conduct. His interactions—whether hot-wiring a car, meeting with the mechanic to receive a gun, or executing his meticulous alibis—are portrayed with quiet precision. Alain Delon’s performance is defined by his poker-faced detachment, embodying a character who is both professional and existentially isolated. His character exudes an impenetrable stillness, and as the reviewer notes, even his beauty becomes irrelevant under this impassive mask.

The film is notable for how Melville eschews conventional action sequences in favor of character-driven tension. Instead of constant physical action, the suspense comes from watching Jef navigate a complex web of betrayal, suspicion, and surveillance. Melville revels in process, showing how Jef is hunted by both the police and the underworld while he silently pursues his own form of justice. The scene where he’s tailed by undercover cops in the Paris Metro is a perfect example of the film’s ability to build tension through quiet, deliberate actions rather than explosive set pieces.

One of the most fascinating aspects of Le Samouraï is its exploration of Jef’s interactions with the two women in his life—Jane, who provides him an alibi, and Valérie, the nightclub pianist who spares him in the lineup. Both women reflect Jef’s existential detachment, complicating the usual femme fatale trope of film noir by showing that they are as elusive and emotionally distant as Jef himself.

The review also touches on Melville’s use of subtle humor, such as the bird in Jef’s apartment, whose chirps are recorded on the police’s bugging device, adding a wry touch to an otherwise stark setting. The barren room, save for cigarettes and water bottles, underscores Jef’s disciplined, almost ascetic existence.

Finally, Melville’s control over the film’s visual and thematic elements culminates in a conclusion where Jef’s actions speak louder than words. He returns to the nightclub, accepts his fate, and stages his own demise, adhering to a code that’s never explicitly stated but deeply felt. The film’s restraint, from its color palette to its dialogue, solidifies Le Samouraï as a masterclass in minimalist filmmaking, where silence and suggestion carry the emotional and narrative weight.

Melville’s explanation about his approach to filmmaking emphasizes his deliberate choice to detach his films from specific time periods and reject realism. By avoiding contemporary trends, like miniskirts or hatless men, he creates a timeless, almost dreamlike atmosphere. His films, such as Le Samouraï, operate within a space that blends reality with fantasy. Melville believes that films should transcend mere documentation of life, instead leaning into the “fantastic” to evoke deeper, more universal emotions and ideas. His “transposition” from realism to fantasy allows audiences to experience this shift subtly, creating an immersive, almost hypnotic experience that avoids the constraints of a specific era or rigid realism.

This description portrays the samurai as a figure both timeless and out of place, blending the ethos of an ancient warrior with the aesthetics of modern noir. By wearing a fedora and trench coat, his appearance contrasts sharply with his traditional role, suggesting he exists in a world that no longer values his code of honor. He clings to meticulous rituals—the positioning of his hat, the cadence of his voice—echoing the precision and grace of an artist. He becomes a symbol of dignity and poise amid a world filled with compromise, evoking the same transcendent qualities found in poets like Cocteau’s Orpheus, whose every action feels deliberate and eternal. His “essence” lies not just in his skill as a killer but in his ability to transform the mundane into something nearly poetic, defined by rhythm, elegance, and discipline.

In his 1997 review of Le Samouraï, later featured in his The Great Movies collection, Roger Ebert awarded the film a perfect four out of four stars. Ebert praised director Jean-Pierre Melville for his ability to captivate the audience with minimalistic yet powerful filmmaking. He likened Melville’s technique to that of a painter or musician, noting how he creates a “spell” through the use of cold, muted light and colors, primarily grays and blues. These visual elements, combined with carefully chosen actions that replace dialogue, immediately immerse the viewer in the film’s atmosphere, showcasing Melville’s mastery in creating an evocative, mood-driven narrative.

Le Samouraï: Death in White Gloves is an essay by David Thomson featured in the Criterion Collection. In this essay, Thomson delves into the film’s intricate blending of style and substance, emphasizing its portrayal of a cold, calculated world where the hitman protagonist, Jef Costello, moves with precision and grace. The “white gloves” symbolize the meticulous nature of both the character and the film itself, highlighting Jean-Pierre Melville’s attention to detail, control of atmosphere, and the minimalist aesthetic that gives Le Samouraï its timeless quality.

Photos courtesy Google. Excerpts taken from Google.