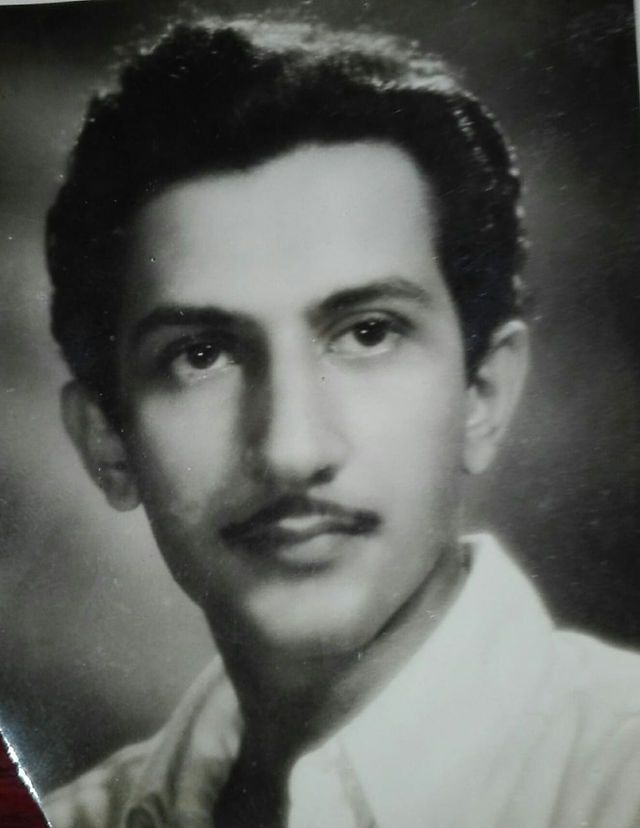

Jal Mistry, born in Bombay in 1923, worked in Indian films as a cinematographer between 1949 and 1998. Jal, known for his low-key high-contrast lighting, shot over 60 films and bagged four Filmfare Awards during his career. Known for his exceptional visual storytelling, he frequently collaborated with director Chetan Anand and the iconic Navketan Films.

Jal Mistry’s passion for cinema and photography was deeply rooted in his upbringing. He and his elder brother, Fali Mistry, another towering figure in the black-and-white era of Hindi cinema, were greatly influenced by their family’s involvement in the world of film and photography. Their father, Dhunjishaw Mistry, played a pivotal role by providing access to a vast collection of books and magazines, both local and international, that opened the brothers’ eyes to the larger world of cinema at a young age. Additionally, their uncle’s ownership of India’s first distribution outlet for Ilford Films in Bombay further fueled their interest in the technical aspects of cinematography.

From early on, the Mistry brothers were inspired by the innovative lighting techniques used in Hollywood and European films, particularly the use of backlighting and low-key contrast lighting to create mood and atmosphere. Jal Mistry, in interviews, fondly recalled how he would watch Hollywood classics at home, taking screenshots of scenes he admired, and then enlarging them to study the lighting in intricate detail.

One film that had a lasting impact on him was John Ford’s How Green Was My Valley (1941), a drama set in the Welsh mining fields, celebrated for its exquisite cinematography by Arthur C. Miller. Mistry described this film as being “engraved in his mind,” reflecting how deeply it influenced his own approach to lighting and visual composition.

The early exposure to such cinematic masterpieces, coupled with his dedication to studying lighting and imagery, helped Jal Mistry develop the refined, emotive visual style that later defined his work in Indian cinema.

In Raj Kapoor Speaks, Ritu Nanda recounts the pivotal moment that launched Jal Mistry’s career as an independent cinematographer with Barsaat (1949). Kapoor, inspired by Greg Toland’s groundbreaking use of the wide-angle lens in Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane (1941), wanted to incorporate similar techniques in Barsaat.

Mistry had already begun building a foundation in the film industry, having started as an apprentice at Siri Sound Studios in Mumbai. His opportunity to work on Barsaat came after a chance meeting with Raj Kapoor at Famous Cine Laboratories, where Mistry had completed shooting another film as a clash cameraman. Jal Mistry’s journey as a cinematographer took a defining turn when Raj Kapoor, after watching Mistry’s rush prints, was so impressed that he offered him the chance to shoot Barsaat. Mistry’s willingness to experiment with the techniques Kapoor admired, along with his talent, earned him the assignment, marking the beginning of a notable career in Indian cinema.

Mistry, who had been honing his craft, confidently accepted the opportunity, marking the beginning of his illustrious career as a lead cinematographer.

Barsaat, a film that explored the various shades of love, became iconic not only for its emotional depth but also for its visual storytelling. The Encyclopaedia of Hindi Cinema praises Mistry’s work, noting his skillful blending of indoor and outdoor shots, creating seamless transitions that contributed to the film’s aesthetic. Particularly noteworthy were his indoor sets, which were lit so meticulously that they convincingly created the illusion of outdoor spaces.

One of the most famous scenes in Barsaat is the climactic moment where Prem Nath’s character lights the funeral pyre of his lover. Film archivist P. K. Nair drew a parallel between this scene and the funeral sequence in George Stevens’ Shane (1953), praising its powerful expressionism. In this emotionally charged moment, Mistry used a low-angle close-up of Prem Nath’s grief-stricken face, illuminated by the flames, to capture the character’s profound sorrow. This shot stands out for its raw intensity and is often regarded as one of the most memorable visual moments in Indian cinema.

Mistry’s work on Barsaat not only helped elevate the film but also cemented his status as a master of visual storytelling, particularly through his innovative use of lighting and angles to evoke deep emotions. The success of Barsaat not only established Mistry as a cinematographer of repute but also helped solidify Kapoor’s standing as a filmmaker who embraced innovation and artistic experimentation.

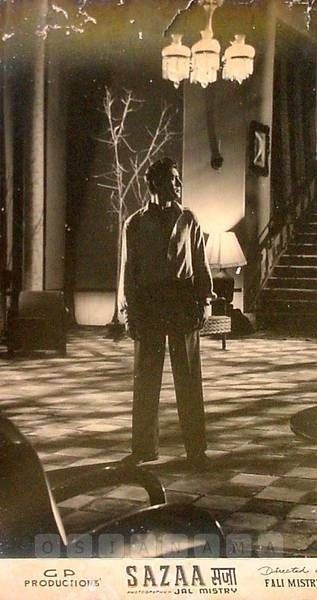

Jal Mistry’s mastery over lighting and composition, influenced by his early exposure to Hollywood and European cinema, can be distinctly observed in his black-and-white films, particularly in Sazaa (1951), directed by his elder brother Fali Mistry. The opening scene of Sazaa is a remarkable example of Jal’s aesthetic sensibility and his ability to evoke mood and tension through visual storytelling.

In this scene, the camera moves into a grand, opulent living room of a bungalow, but what makes it unforgettable is Jal’s use of light and shadow. The room is animated into an eerie, unsettling form by the swaying shadow of a giant chandelier caught in the wind, casting dark, distorted shapes across the walls. This haunting atmosphere, created through careful lighting and dynamic camera movement, sets a foreboding tone even before any dramatic event unfolds.

A few moments later, the tension is broken by a piercing scream, but by that time, Jal’s cinematography has already conveyed a sense of impending doom. His dreamlike visuals, layered with shadows and depth, inform the audience of the underlying tension and fear long before the narrative explicitly does. This scene in Sazaa demonstrates Jal Mistry’s ability to use light and shadow as narrative tools, immersing viewers in an atmospheric, almost surreal experience.

The visual style Jal honed in films like Sazaa speaks to his understanding of cinematography as not just a technical craft but an art form capable of influencing emotions and storytelling through subtle, yet powerful imagery.

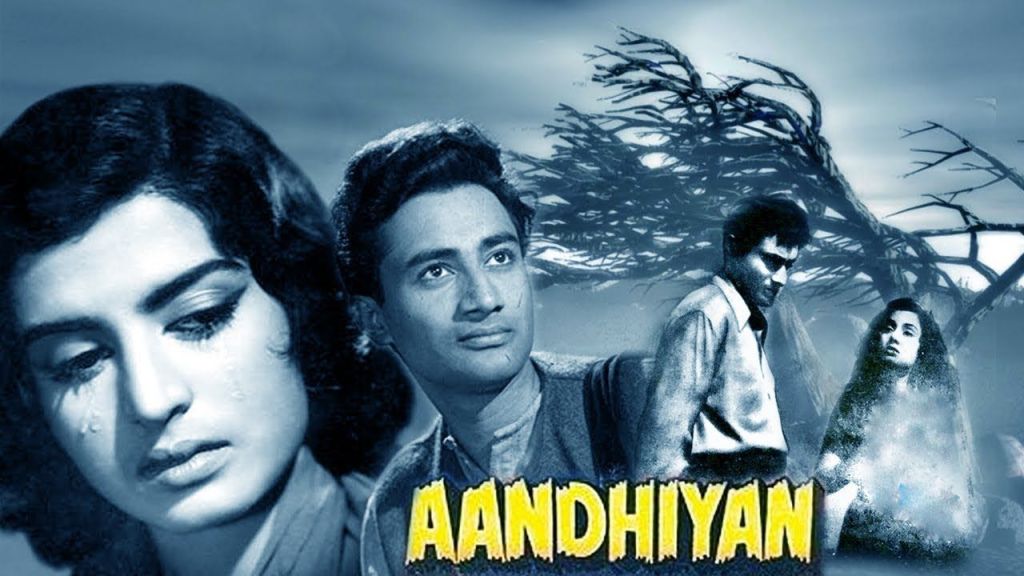

Actress Nimmi, who starred in the 1952 film Aandhiyan, directed by Chetan Anand and shot by Jal Mistry, recalled the dedication of the director and cinematographer in an interview. She described how they patiently waited for seven days to capture the perfect red sky before shooting the crucial storm sequence. This attention to detail and commitment to visual authenticity was a hallmark of their collaboration, showcasing their willingness to allow nature and lighting to dictate the scene rather than rushing the production.

In Aandhiyan, the storm sequence was pivotal to the film’s atmosphere and emotional impact, and both Anand and Mistry were determined to ensure it was shot under ideal conditions. The red sky they waited for wasn’t just a backdrop; it was a key element in the dramatic build-up, enhancing the sense of foreboding and intensity.

Writer-researcher Debashree Mukherjee also delves into the film’s production in her book A Material World: Notes On An Interview. She quotes Ram Tipnis, an actor and make-up artist, highlighting how such meticulous care in the shooting process reflected the broader commitment of filmmakers like Anand and Mistry to their craft. They weren’t just concerned with technical perfection but also with capturing the emotional and atmospheric nuances that would deepen the audience’s experience of the story.

This anecdote about Aandhiyan exemplifies the kind of dedication and artistic vision that made Jal Mistry a celebrated cinematographer. His ability to harness natural elements, like the sky, to elevate the emotional depth of a scene was a key feature of his style, often resulting in unforgettable visual moments in his films.

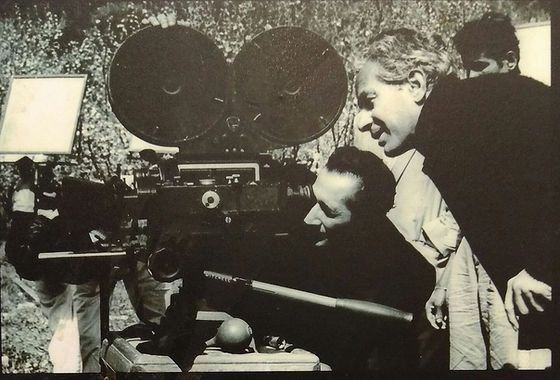

Jal Mistry’s collaboration with director Chetan Anand and Navketan Films led to some of his most innovative and visually captivating works, with Aakhri Khat (1966) standing out as a particularly bold and experimental film. This film marked the debut of Rajesh Khanna and was centered around the deeply emotional story of a toddler, Bunty Behl, lost in the bustling city of Bombay. Chetan Anand’s decision to abandon a traditional shooting script for the scenes involving the toddler was unconventional and risky, allowing the young child to move freely through real locations, such as busy roads and railway tracks in Mahim. Jal Mistry’s task was to capture these spontaneous and unplanned moments, using a handheld camera to follow the child’s movements in an almost documentary-like style.

This approach contributed to the film’s semi-documentary aesthetic, emphasizing the realism and rawness of the story. Mistry’s handheld camera work added an organic, intimate feel to the film, making the audience experience the chaos and vulnerability of the child’s perspective in the overwhelming cityscape.

In contrast, the song Rut Jawan, where Bhupinder Singh performs as a jazz musician, showcased another side of Jal Mistry’s artistry. Here, Mistry employed more structured techniques, using trolley shots to enhance the fluidity of the scene and creating a visually dynamic experience. The use of low-key lighting added a moody, jazz-infused atmosphere, characteristic of Mistry’s signature style, particularly when working with indoor lighting.

Aakhri Khat was an experimental departure for Chetan Anand, and Jal Mistry’s cinematography played a crucial role in its unique cinematic language. Author-filmmaker Helio San Miguel, in World Film Locations: Mumbai, praised the film for its “non-linear narrative, semi-documentary style, bold imagery, and a jazzy soundtrack,” noting how it surpassed conventional filmmaking with its inventive form. Mistry’s ability to adapt to different visual styles, from the raw realism of handheld shots to the stylized low-key lighting in the jazz scene, made Aakhri Khat a landmark film in Indian cinema.

Mistry’s collaboration with Anand in Aakhri Khat demonstrates his versatility as a cinematographer, capable of balancing spontaneous, naturalistic moments with carefully crafted, atmospheric imagery, contributing to the film’s lasting impact.

Jal Mistry won his first Filmfare Award in 1968 for his outstanding work on Baharon Ke Sapne (1967), directed by Nasir Hussain. This intense drama focused on the themes of unemployment and the struggles of the working class, with a young Rajesh Khanna headlining the cast. Mistry’s cinematography played a pivotal role in amplifying the film’s emotional depth and its depiction of class conflict.

The film’s final sequence is one of the most memorable, both for its visual power and emotional intensity. As the workforce, driven to rage by their dire circumstances, sets a mill ablaze, the camera captures the chaotic and destructive energy of the scene. Amidst the chaos, Rajesh Khanna’s character, who is gravely injured and wrongly accused of betraying his class, makes his way towards the rioting mob. In a stunning, awe-inspiring shot, Mistry’s camera captures Khanna limping through the smoke-filled air, the burning mill casting an apocalyptic glow behind him. The shot is both visually striking and symbolically charged, with the hero calling for peace despite the flames of anger and destruction surrounding him.

This climactic scene, with its haunting imagery of smoke rising to the sky and the juxtaposition of fire and human desperation, exemplifies Jal Mistry’s ability to convey deep emotional resonance through visual storytelling. The use of light, shadow, and framing in this sequence heightens the tension and drama, making it one of the most powerful moments in Baharon Ke Sapne.

Mistry’s award-winning work on this film highlights his exceptional skill in bringing complex, emotionally charged narratives to life, solidifying his reputation as one of the finest cinematographers in Indian cinema.

Jal Mistry’s contributions to Indian cinema extended beyond his renowned work as a cinematographer; he also ventured into production, showcasing his versatility within the industry. One notable project was Bombai Ka Babu (1960), which he co-produced alongside director Raj Khosla. Starring the iconic Dev Anand, the film allowed Mistry to engage with the filmmaking process from a broader perspective, integrating his artistic vision with the production side of cinema.

By stepping into the role of producer, Mistry demonstrated that his expertise wasn’t confined to capturing images on film. His involvement in production reflected his deep understanding of the entire filmmaking process, from the conceptual stage through to execution. This multifaceted approach not only enriched his own career but also contributed to the collaborative environment of the film industry.

One of Mistry’s ingenious techniques involved using battery-operated pen lights mounted on the camera to illuminate the eyes during close-up shots. This subtle touch added depth and emotion to the performances, drawing the audience’s attention to the actors’ expressions.

He also worked as the film’s cinematographer. In the thriller that film historian Gautam Chintamani regards as the starting point of Hindi cinema’s Angry Young Man genre, Jal captures unique close-up shots of the faces of the lead stars Devanand and Suchitra Sen, emphasizing their expressive eyes.

Bombai Ka Babu is remembered for its engaging storyline and strong performances, and Mistry’s influence as a co-producer likely played a role in shaping its production values. This film stands as a testament to his adaptability and commitment to cinema, proving that his passion for storytelling and visual art extended well beyond the camera lens. Mistry’s ability to contribute to multiple facets of filmmaking further solidified his legacy as a significant figure in the history of Indian cinema.

Jal Mistry’s work on Naseeb, directed by Manmohan Desai, showcased his ability to excel under pressure. Given only ten minutes to set the lighting for the main stars due to a tight schedule, Mistry and his camera team had to efficiently light the entire set two days in advance for the party scenes. This level of preparation was crucial in ensuring that everything was ready for the shoot, allowing for a seamless filming process.

Mistry was renowned for his expertise in facial lighting, particularly in the black-and-white medium. He employed diffusers—a technique commonly used by still photographers—to achieve a soft, flattering light on the heroines’ faces. This approach effectively reduced harsh shadows and helped mask thick makeup, enhancing the overall appearance of the actresses on screen.

In Kudrat, Mistry experimented further with his lighting techniques, incorporating thin, mild gauze—delicate black chiffon fabric imported from London—and fog filters. This innovative approach allowed him to create a moody atmosphere with heightened contrast, enriching the visual storytelling and adding a layer of complexity to the film’s imagery.

Mistry’s ability to adapt and innovate within the constraints of different projects exemplifies his artistry and mastery of cinematography, solidifying his reputation as a pivotal figure in the Indian film industry.

One notable instance of Mistry’s involvement was during the extended production of Kamal Amrohi’s classic film Pakeezah (1972). Due to the absence of the principal cinematographer, Josef Wirsching, Mistry stepped in to shoot several scenes, showcasing his versatility and skill. Pakeezah is celebrated for its stunning visuals and intricate art direction, and Jal’s contributions during this pivotal film added to its overall aesthetic appeal.

Jal Mistry’s exceptional talent was recognized with four Filmfare Awards for Best Cinematography throughout his illustrious career. He received these accolades for his outstanding work in Baharon Ke Sapne (1968), Heer Raanjha (1971), Jheel Ke Us Paar (1974), and Kudrat (1982). Each of these films showcased his mastery in creating visually stunning and emotionally resonant imagery, cementing his legacy in Indian cinema.

At the age of 75, Mistry shot his final film, Jhoot Bole Kauwa Kaate. Even at this stage in his life, he expressed a desire to continue working in cinematography, emphasizing his passion for the art. He stated, “Camerawork is a fascinating art. I would like to continue even now, but with the right film.” His extensive travels abroad had broadened his perspective, leading him to reflect on the advancements and techniques he observed in international cinema. He lamented, “After travelling so much abroad, I feel that we should have all the things that they have, but where is it?” This sentiment highlights his aspiration for the Indian film industry to embrace more modern techniques and facilities, allowing for greater artistic expression.

Mistry’s dedication to his craft, combined with his visionary outlook, left a lasting impact on cinematography in Indian cinema. His ability to capture the nuances of light and shadow created a visual language that resonated with audiences, making him one of the most respected cinematographers of his time.

Jal Mistry was widely recognized in the Hindi film industry not just for his remarkable talent, but also for his meticulous approach to cinematography. Colleagues often described him as taciturn, yet his perfectionism spoke volumes about his dedication to his craft. His lighting style was so distinctive that it earned the phrase “Jal Ki Jaali” (Jal’s Net), highlighting his genius in creating intricate and beautiful visual textures.

Mistry’s commitment to achieving the perfect lighting setup was evident in his methods. In an interview with cinematographer CK Muraleedharan, he shared, “Now, once I lit up the set, it would stay so. Before the artistes would come, I would place some people as stand-ins and make it so perfect that when the artistes arrived and did the rehearsal, there would be only slight little change.” This meticulous attention to detail ensured that the lighting was flawless by the time the actors arrived, allowing for a smoother rehearsal process and ultimately enhancing the quality of the final shot.

The level of dedication Mistry brought to his work is further illustrated by a notable anecdote regarding a close-up shot of the legendary actress Nutan. It reportedly took six hours to get the lighting just right, a testament to Mistry’s patience and precision. The result, however, was worth the wait; the beauty of the shot on screen left a lasting impression on those involved.

This commitment to excellence and his artistry in lighting not only defined Jal Mistry’s career but also elevated the visual quality of the films he worked on, leaving an indelible mark on Indian cinema. His legacy as a perfectionist continues to inspire cinematographers today, emphasizing the importance of lighting in storytelling through film.

Photos courtesy Google. Excerpts taken from Google.