Diksha (1991), directed by Arun Kaul, is an evocative film based on the Kannada novel Ghatashraddha by U. R. Ananthamurthy. The film explores themes of tradition, societal norms, and moral dilemmas in a rigid Brahminical society.

Diksha is set in the early 1930s and presents a powerful exploration of the clash between orthodox traditions and human frailties. The story is centered around a Brahmin guru (Panditji), his young widowed daughter, his head disciple, and a low-caste man named Koga, who dreams of mastering the sacred scriptures, despite his social standing.

The narrative takes a dramatic turn when, in a moment of vulnerability during the guru’s absence, the widowed daughter succumbs to her desires and engages in a forbidden relationship. When she becomes pregnant, the societal pressures and strict Brahminical norms force her to seek an abortion after her lover refuses to acknowledge his responsibility. The shame and stigma attached to her actions create a profound crisis within the tightly knit community.

The widow’s transgression leads to her being ostracized and subjected to harsh punishment in accordance with the rigid customs of the time. As the guru returns, he is caught in a moral quandary—torn between the honor of upholding the traditions that define his standing and the compassion he feels for his daughter. Koga’s story, meanwhile, represents the struggle of the marginalized who, despite their talents and desires, are denied entry into the intellectual and spiritual spheres controlled by the upper castes.

The film critiques the rigid caste system and oppressive social norms that govern the lives of women and lower-caste individuals. It questions the inflexible nature of societal rules, particularly in the context of gender and caste, and reflects on the human cost of adhering to such structures. Diksha poignantly portrays how one woman’s tragic mistake triggers a broader examination of morality, compassion, and the boundaries of tradition.

Diksha intricately portrays the conflict between tradition and morality through the figure of Panditji, a scholar bound by the rigid customs of the Brahminical order. The widow’s pregnancy forces Panditji into a moral dilemma—whether to follow the severe societal rules that demand her excommunication through ghatashraddha, a symbolic “death” within the Brahmin tradition, or to act with compassion toward his daughter. The film captures the deep-rooted orthodoxy that governs the lives of women, widows, and marginalized communities within this setting.

Panditji’s internal struggle symbolizes the broader conflict faced by those in positions of authority within oppressive structures. As a father and a scholar, he is torn between his duty to tradition and his own moral compass, which urges him to show compassion to his daughter despite her actions. This tension reflects the larger theme of the film: the burden of upholding societal expectations while grappling with the consequences they impose on individuals, particularly those without power or status.

Diksha beautifully captures the film’s exploration of the rigid and oppressive Brahminical social order. The characters, particularly the young widow and Koga, serve as symbols of those marginalized by caste and gender hierarchies. Their struggles highlight the inhumanity embedded within tradition, where adherence to religious customs often overrides the need for empathy and fairness.

Panditji’s adopted son indeed plays a crucial role in the narrative, embodying the tension between tradition and change. His observations of the injustice around him reflect the younger generation’s ability to either challenge or uphold these age-old norms. This conflict adds depth to the film’s message, questioning whether society can evolve without sacrificing compassion or if tradition must always come at the expense of humanity.

Diksha emphasizes its powerful critique of traditional practices, especially through the tragic climax involving Panditji’s heart-wrenching decision to declare his daughter ghatashraddha. This ritualistic excommunication highlights the film’s stark portrayal of how rigid social customs can destroy lives, severing familial and social bonds in the name of upholding tradition. Panditji’s act, performed with the full weight of societal pressure, demonstrates the brutal consequences of prioritizing dogma over compassion.

The film’s nuanced depiction of the aftermath—where the seemingly righteous act of tradition sparks a silent rebellion—further deepens its moral complexity. The head disciple’s disillusionment represents a generational conflict, as he grapples with the clash between the values he was taught and the reality of their application. Nanni’s return to his parents, likely filled with newfound skepticism, subtly questions the sustainability of a system that punishes instead of protects.

Koga’s rejection of Brahminical promises is especially poignant, symbolizing the growing defiance against a social structure that marginalizes and dehumanizes. His rejection is not just personal but serves as a broader critique of a tradition that fails to grant dignity and equality to all. Diksha’s realism and delicate handling of these themes allow it to advocate for a more humane balance between justice and societal expectations, asking viewers to reflect on the moral cost of adhering to oppressive customs.

Diksha‘s final act astutely captures the tension between tradition and personal morality that defines the film. Panditji’s decision to sacrifice his daughter’s well-being for the sake of upholding societal norms underscores the dehumanizing effects of blind adherence to orthodoxy. His internal struggle represents the tragic conflict faced by individuals caught between their personal emotions and their roles as enforcers of tradition.

The reactions of those around him—those who leave or reject the system—highlight the potential for individual defiance to challenge entrenched practices. This quiet rebellion suggests that while oppressive traditions are often upheld by collective forces, their legitimacy can begin to crumble when individuals choose to question and reject them. Diksha thus raises important questions about the moral responsibility of those in positions of authority, and whether tradition should be upheld at the cost of humanity and compassion.

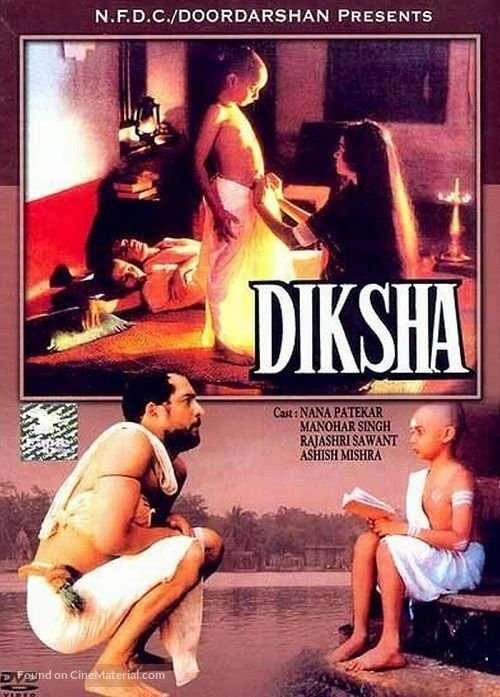

The performances in Diksha highlights how the cast brings emotional depth to the film’s exploration of tradition versus personal morality. Nana Patekar and Manohar Singh, in particular, deliver nuanced portrayals that embody the conflict between individual emotions and societal expectations. Singh’s depiction of Panditji, a guardian of tradition who must navigate the devastating consequences of his daughter’s perceived dishonor, is a powerful portrayal of a man torn between his role and his personal anguish.

Vinay Kashyap and KK Raina, as disciples in the gurukul, further enrich the narrative by representing the younger generation’s growing awareness of the hypocrisy and injustice within the Brahminical system. Their reactions to the events around them underscore the quiet questioning of orthodoxy, as they observe the toll that blind adherence to tradition takes on individuals.

Set against the backdrop of pre-independent South India in a deeply traditional Brahmin society, the film’s setting within a gurukul amplifies its themes, as an institution meant to impart wisdom becomes a space where rigid customs prevail over compassion.

Diksha (1991) received widespread critical acclaim, winning several prestigious awards for its thought-provoking narrative and strong performances. It was awarded the 1992 National Film Award for Best Feature Film in Hindi, recognizing its excellence in storytelling and its depiction of societal issues within a traditional Brahminical context. The film also won the 1992 Filmfare Critics Award for Best Movie, highlighting its artistic merit and sensitive handling of complex themes like caste and gender oppression.

Diksha is based on U. R. Ananthamurthy’s novel Ghatashraddha, which had previously been adapted into a 1977 Kannada movie Ghatashraddha. That version had also been highly acclaimed, winning the 1977 National Film Award for Best Feature Film, making both adaptations powerful reflections on Brahmin society and its impact on individuals.

The 1991 adaptation of Diksha gained international recognition as well, participating in the International Film Festival of India in 1993. It went on to win several international awards, including:

- The Annonay International Film Festival Award in France, 1992.

- The Prix Du Public (Audience Award).

- The Best Feature Film in Hindi by the Madhya Pradesh Development Corporation, 1992.

Photos courtesy Google. Excerpts taken from Google.