Antarjali Jatra is a poignant 1987 Bengali film directed by Goutam Ghose and based on a novel by Kamal Kumar Majumdar, is a powerful portrayal of the oppressive and dehumanizing traditions that plagued 19th-century Indian society.

The story focuses on Seetaram, an elderly Brahmin whose death ritual is manipulated to secure religious merit and social prestige. The narrative spotlights the inhumane practice of sati, outlawed yet still clandestinely practiced under the guise of ritualistic purity and familial greed.

Yashobati, the young bride coerced into this grim marriage, embodies the tragic fate of women in a society steeped in patriarchal and casteist norms. The film is deeply critical of how religious dogma and societal pressure can lead to moral compromises and devastating consequences for vulnerable individuals.

Yashobati, thus trapped in a life-threatening union, is taken to live with her dying husband at the cremation ground. There, she awaits the death of her elderly “groom” and her own expected fate as a sacrificial widow, embodying the tragic weight of societal and religious customs. The film poignantly underscores the exploitation and moral decay of practices that oppress women, raising questions about tradition, human dignity, and the fight against systemic injustice.

The story takes a dramatic turn as the harsh patriarchal system orchestrates a flawless setup to ensure the ritual is followed, except for one unexpected obstacle: Baiju, a drunk yet compassionate chandala who resides on the cremation ground. He perceives the entire act as deeply unjust and becomes determined to prevent the ritual’s tragic conclusion. Baiju tries to convince Yashobati to escape, but shackled by the oppressive chains of tradition, she refuses, resigned to her fate.

The narrative reaches a critical moment one night when Baiju, driven by his moral outrage, attempts to kill Seetaram to end the cruel setup. Yashobati intervenes, embodying the loyal wife, and tries to stop him. Their confrontation on the muddy banks of the Ganga becomes intense and emotional, culminating in an unexpected moment of intimacy that shifts their struggle into lovemaking. As they are engulfed by the swelling waters of the river, both Seetaram and Yashobati are swept away, symbolically erasing the boundaries of societal norms and the oppressive fate imposed on them. This conclusion underscores the power of natural forces and human emotion against the rigidity of patriarchal traditions.

Yashobati, the young bride in Antarjali Jatra, is a central figure symbolizing the innocence and powerlessness of women in a rigidly patriarchal society. Forced into a marriage with a dying man, Seetaram, her fate highlights the grim reality of how women were often treated as sacrificial objects for the supposed greater good of their families’ social and spiritual aspirations.

Despite being a young girl with dreams and potential, Yashobati is stripped of her autonomy when her impoverished Brahmin father agrees to the marriage, seduced by the promise of financial relief. Her character serves as a vessel through which the film explores themes of exploitation, gender inequality, and the brutality of religious and social traditions.

Yashobati’s plight, brought to life through poignant storytelling and heartfelt performance, evokes empathy and outrage. Her role underscores the emotional and physical toll of practices like sati, emphasizing the stark contrast between societal ideals of honor and the individual suffering they often masked. Yashobati, raises profound questions about morality, duty, and the true cost of upholding tradition at the expense of human life.

Goutam Ghose, the filmmaker behind Antarjali Jatra, contextualized the film within a period of significant societal upheaval and renewal. The setting, the 19th-century Bengal Renaissance, was a time when long-established customs and practices within Hindu society began to face intense scrutiny and reform. Ghose pointed out that while these customs had been rooted in antiquity, they often thrived on misinterpretations of religious texts, as the majority of Brahmins were either illiterate or only newly literate. This lack of widespread, accurate understanding made Hindu scriptures vulnerable to distortion and misuse. Ghose’s attention to period detail vividly bring to life the harrowing reality of rural Bengal, showcasing human suffering under the weight of archaic customs. The film is both a poignant critique of ritualistic exploitation and a somber reminder of the historical and cultural battles against such practices.

Satidaha, or sati, the practice of burning Brahmin widows on their husbands’ funeral pyres. While this ritual was defended as a sacred act by conservative elements within society, it was increasingly challenged as a barbaric and oppressive practice, known to the Western world as suttee.

The cinematography of Antarjali Jatra is indeed one of its most compelling aspects. Goutam Ghose masterfully uses long, contemplative shots that capture the stark reality of life along the muddy banks of the Ganga. These visuals evoke both a sense of raw authenticity and an atmosphere of deep introspection. The framing alternates between revealing the harsh, unembellished truth of the setting and creating a brooding, almost poetic tone that lingers with the viewer. This cinematographic approach enhances the emotional weight of the story, emphasizing the isolation and desolation faced by the characters.

The film’s performances are equally noteworthy, adding depth to its complex narrative. Shatrughan Sinha stands out for his portrayal of Baiju, a role that starkly contrasts with his usual Bollywood persona. Known for his flamboyant and intense roles in mainstream cinema, Sinha’s performance in Antarjali Jatra is subtle, layered, and deeply empathetic. His portrayal of a compassionate chandala grappling with the injustices around him showcases his versatility as an actor and brings a sense of humanity to the film. Overall, the strong performances and evocative cinematography combine to make Antarjali Jatra a powerful, visually and emotionally resonant film.

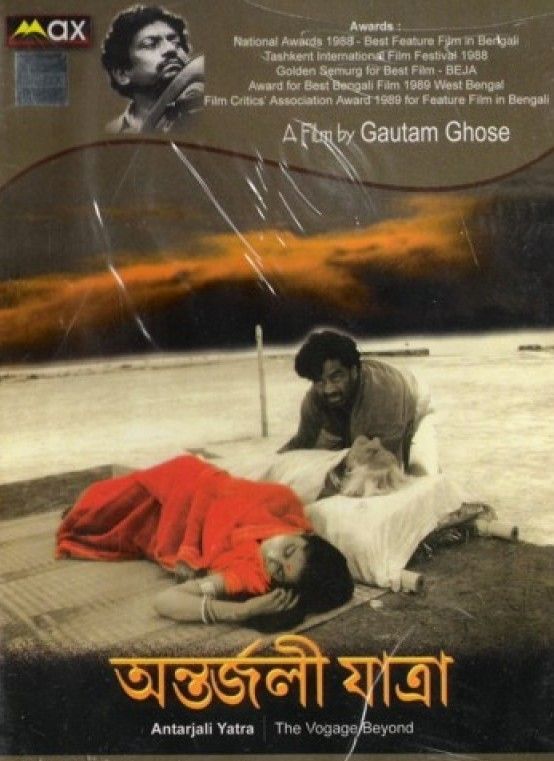

Antarjali Jatra (The Ultimate Journey) received significant recognition for its powerful storytelling and thematic depth. It won the National Film Award for Best Feature Film in Bengali in 1988, celebrating its artistic and cultural significance in Indian cinema.

The film was also screened in the Un Certain Regard section at the 1988 Cannes Film Festival, showcasing it to an international audience and highlighting its impact on a global scale. Additionally, Antarjali Jatra was honored with the Grand Prix at the Tashkent Film Festival in 1988, further solidifying its status as an important work that resonated with audiences and critics both in India and abroad.

Photos courtesy Google. Excerpts taken from Google.