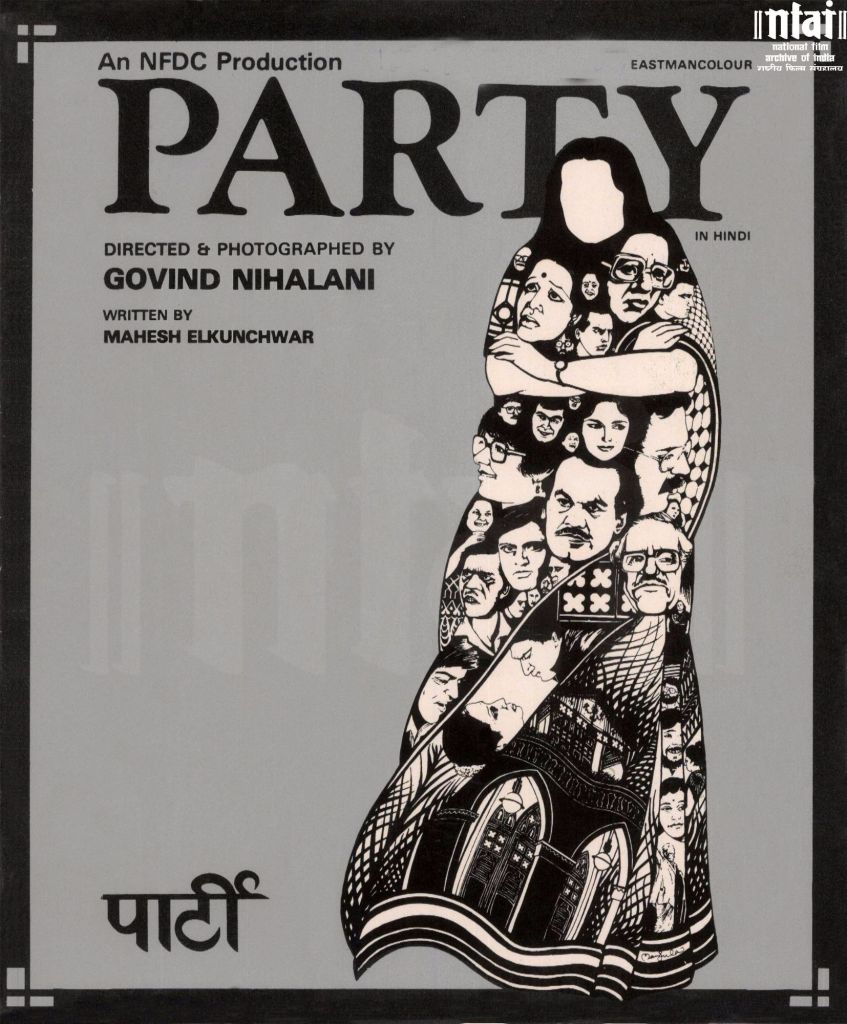

Party (1984) is a remarkable film that offers a critique of the urban intellectual class. It’s often praised for its intelligent script, strong performances, and its exploration of complex social and political themes. Directed by Govind Nihalani, the film’s ensemble cast, including Vijaya Mehta, Manohar Singh, Om Puri, Naseeruddin Shah, and Rohini Hattangadi, all contribute to its impactful narrative.

Party is a prime example of the socially conscious cinema that the National Film Development Corporation of India (NFDC). By focusing on a single gathering, the film creates an intimate yet scathing portrait of the intellectual elite—people who claim to care about political and social issues but remain insulated from the struggles of the common people. Nihalani’s direction ensures that the characters’ pretensions unravel gradually, exposing their contradictions in a way that feels both organic and deeply unsettling.

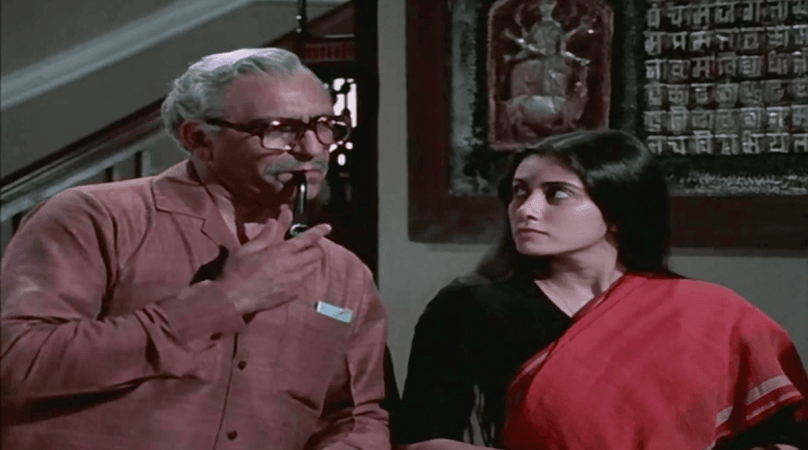

Nihalani’s decision to set Party in a single evening at Damyanti Rane’s (Vijaya Mehta) house is a brilliant choice, as it gives the film a sense of immediacy and intensity. The real-time unfolding of events allows the tension to build gradually, highlighting the characters’ vulnerabilities and their moral contradictions. The microcosm of the intellectual elite at the party represents not just the specific circle but also the broader urban intellectual class in India, their self-awareness, and their often misplaced sense of superiority.

Damyanti’s party becomes a space where the guests’ facades crack, revealing their deeper insecurities and contradictions. Diwakar Barve (Manohar Singh), in particular, serves as a key figure of this critique. Though celebrated as a playwright, his detachment from the pressing issues around him—especially the social and political realities—forces viewers to reflect on the gap between artistic renown and societal engagement. His character exposes how some intellectuals, despite their public stature, can become blind to the needs of the real world.

Many of the guests seem to use their ideological stances as a means of self-validation rather than genuine commitment. They discuss oppression, injustice, and revolution, but their engagement remains theoretical, lacking real-world action. The contrast between their rhetoric and their inaction is particularly striking when compared to Amrit (Naseeruddin Shah), the absent poet-revolutionary whose presence looms over the film. His commitment to social causes, unlike the others, is not just philosophical but lived—he has chosen the difficult path of direct involvement, making him both an ideal and a rebuke to the others at the party.

Many of the guests seem to use their ideological stances as a means of self-validation rather than genuine commitment. They discuss oppression, injustice, and revolution, but their engagement remains theoretical, lacking real-world action. The contrast between their rhetoric and their inaction is particularly striking when compared to Amrit (Naseeruddin Shah), the absent poet-revolutionary whose presence looms over the film. His commitment to social causes, unlike the others, is not just philosophical but lived—he has chosen the difficult path of direct involvement, making him both an ideal and a rebuke to the others at the party.

The film’s critique extends beyond individual hypocrisy to a broader examination of India’s cultural and political climate. It questions whether intellectual discourse, when devoid of real action, holds any meaning. Through the contrast between the guests at the party and the absent Amrit, Nihalani forces the audience to confront uncomfortable truths about privilege, responsibility, and the cost of genuine activism.

Amrit, the poet turned political activist, becomes the enigmatic and almost mythical figure around which the film’s discussions revolve. His absence from the party itself is telling—his commitment to the cause of the tribals in Andhra contrasts starkly with the self-indulgence of the elite attendees. Nihalani’s choice to hold back Amrit’s appearance until the film’s violent conclusion enhances his symbolic weight, representing an alternative to the shallow, performative activism of the partygoers.

The atmosphere of the party in Party undergoes a dramatic shift with the arrival of Avinash (Om Puri), a character whose presence introduces a stark contrast to the otherwise polished and pretentious ambiance of the gathering. Avinash, a disillusioned journalist and former close friend of Amrit, brings with him a sense of raw truth and unvarnished reality that unsettles the partygoers.

Unlike the other guests, who are comfortably ensconced in their intellectual bubbles, Avinash is not afraid to confront their hypocrisy. His arrival disrupts the superficial conversations and forces the attendees to confront the deeper, unresolved issues lurking beneath the surface. Avinash’s biting cynicism and sharp observations challenge the comfortable narratives that the guests have constructed around themselves, and his intimate knowledge of Amrit’s integrity stands as a reminder of the moral decay in the room.

Avinash’s entrance acts as a catalyst for the tension that has been building throughout the evening. His harsh critiques and pointed remarks expose the emptiness of the intellectual pretensions of the partygoers, and his presence evokes the absent Amrit even more strongly, making everyone aware of their complicity in abandoning the true purpose of art and activism. The shift in atmosphere, from one of casual elitism to uncomfortable self-reflection, pushes the narrative towards its eventual devastating conclusion.

The title Party works on multiple levels, capturing both the literal gathering and the metaphorical political and ideological affiliations that shape the characters’ identities. Nihalani uses this setting to expose the contradictions within the so-called intellectual elite—people who talk about social change and political issues but remain insulated in their privileged circles.

Party stands out as one of Nihalani’s finest works precisely because of its unflinching critique of intellectual pretension. The film’s power lies in its ability to expose the characters’ moral and ideological contradictions through their own words—long, verbose conversations that initially seem sophisticated but gradually reveal their emptiness. Nihalani masterfully uses dialogue as a weapon, peeling away layers of self-righteousness to reveal a deep-seated apathy beneath.

The slow, deliberate pacing allows tension to simmer throughout the evening, making the final moments all the more jarring. The film’s climax—abrupt, violent, and deeply unsettling—acts as a brutal reminder that real struggles exist beyond drawing-room debates. It serves as a wake-up call, showing that while the guests indulge in rhetorical battles, the world outside remains unchanged, or worse, continues to suffer.

The film’s verbose dialogue, drawn from Elkunchwar’s play, allows each character to unveil their ideologies, insecurities, and betrayals through sharp exchanges. It’s a biting commentary on the intellectual elite’s disconnection from ground realities, particularly in how they romanticize causes like Amrit’s but fail to genuinely engage with them.

Nihalani’s Party remains a standout example of Indian parallel cinema, where rich performances, deep philosophical musings, and social critique blend seamlessly, challenging the audience to confront their own complacency.

A film offers a vibrant and eclectic mix of characters, each representing different walks of life, ideologies, and creative pursuits. The ensemble cast, rich with recognizable talent from 1980s Indian television and theatre, adds a nostalgic charm to the narrative. Gulan Kriplani’s portrayal of a fiery Marxist contrasts sharply with the more pragmatic or creatively burned-out characters like Shafi Inamdar’s thespian and K K Raina’s struggling poet. The presence of a bored model, a curious magazine editor, and various other fleeting but familiar faces builds an engaging atmosphere of intellectual banter, personal dilemmas, and the interplay of high and low culture.

Rohini Hattangadi won the National Film Award for Best Supporting Actress for her role in Party. In the film, Hattangadi delivers a nuanced performance, contributing to the film’s sharp critique of intellectual elitism and the moral decay of the upper echelons of society. Her portrayal added depth to the ensemble cast, making her performance stand out in a film that explores the tension between artistic ideals and societal compromise. This award marked a significant recognition of her acting prowess.

The film was selected as the official Indian entry to the 32nd International Film Festival of India, held in New Delhi, marking its significance in Indian parallel cinema.

Photos courtesy Google. Excerpts taken from Google.