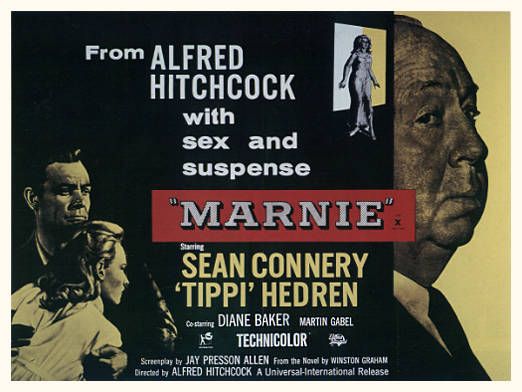

Marnie is a 1964 American psychological thriller directed by Alfred Hitchcock, with a screenplay by Jay Presson Allen, adapted from Winston Graham’s 1961 novel of the same name. The film stars Tippi Hedren as the enigmatic Marnie and Sean Connery as the man determined to unravel her secrets.

Margaret “Marnie” Edgar, operating under the alias Marion Holland, absconds with nearly $10,000 stolen from the company safe of her employer, Sidney Strutt, the head of a tax consulting firm. Marnie had charmed her way into the position without providing references, relying on her beauty and cunning. Meanwhile, Mark Rutland, a wealthy widower and owner of a Philadelphia publishing company, visits Strutt on business. During their meeting, Mark learns about the theft and realizes he recognizes Marnie from a previous encounter at Strutt’s office.

Marnie travels to Virginia, where she boards her beloved horse, Forio, providing a rare glimpse into her softer, more vulnerable side. She then visits her emotionally distant and invalid mother, Bernice, in Baltimore, whom she supports financially. Despite her outward composure, Marnie is plagued by recurring nightmares and suffers from a deep, unexplained aversion to the color red, which consistently triggers episodes of panic and hysteria. These psychological disturbances hint at a buried trauma from her past.

Several months later, Marnie—now using the alias Mary Taylor—applies for a position at Mark Rutland’s publishing firm. Recognizing her immediately, Mark hires her despite the lack of references, telling a colleague that he is merely an “interested spectator.” While working overtime one weekend, Marnie suffers a panic attack during a thunderstorm, revealing her vulnerability. Mark consoles her, and their relationship takes a romantic turn as he kisses her.

However, true to her pattern, Marnie soon steals money from the company and flees. Mark, having anticipated her behavior, tracks her to the stable where she keeps her horse, Forio. Instead of turning her in, he blackmails her into marrying him, hoping to unravel the mystery behind her behavior and help her heal. Their sudden marriage draws the suspicion of Lil, the jealous sister of Mark’s late wife, Estelle, who harbors feelings for Mark. Lil becomes increasingly uneasy when she discovers Mark has been spending large sums of money since marrying Marnie.

During their honeymoon cruise, Marnie continues to resist Mark’s advances, revealing a deep-seated repulsion toward physical intimacy. Initially, Mark tries to respect her boundaries and win her affection gently. However, after several nights of emotional distance, their relationship reaches a breaking point. During a heated quarrel over her detachment, Mark forces himself on her, an act that is not shown but heavily implied, while Marnie becomes emotionally frozen, unable to resist or respond. The next morning, overwhelmed by trauma and despair, she attempts to drown herself in the ship’s swimming pool, but Mark rescues her.

Back home, Lil—who has been growing increasingly suspicious—overhears Marnie on a phone call and discovers that Marnie’s mother is still alive, contrary to what Marnie had claimed. Lil discreetly informs Mark, prompting him to hire a private investigator to look into Marnie’s background. Meanwhile, Lil overhears Mark telling Marnie that he has paid off Sidney Strutt, her previous employer, to keep quiet about her theft.

Scheming to expose Marnie, Lil invites the Strutts to a party at the Rutland mansion. Strutt recognizes Marnie, but Mark coerces him into silence. Later, Marnie confesses to having committed additional thefts in the past. Determined to protect her and uncover the truth behind her behavior, Mark begins reimbursing her victims, persuading them to drop any charges.

In an attempt to comfort her, Mark brings Forio to their estate, delighting Marnie and offering her a rare moment of peace. However, during a fox hunt, the sight of a red riding coat worn by one of the hunters triggers another of Marnie’s violent psychological episodes. Forio bolts in panic, fails a jump, and crashes to the ground, severely injuring his legs. The horse lies screaming in pain, helpless. In a state of shock and anguish, Marnie runs to a nearby house, obtains a gun, and, with trembling hands, euthanizes Forio to end his suffering—a heart-wrenching act that underscores the depths of her emotional trauma.

Devastated and numb, Marnie returns home. There, she finds the key to Mark’s office, and in a trance-like state, she enters and opens the company safe. Yet this time, something is different: despite the open opportunity, she cannot bring herself to steal the money. When Mark arrives and quietly encourages her to take it, as a test of whether she’s truly changed. Marnie remains frozen, unable to repeat her old patterns. It becomes clear that something within her has shifted.

Determined to uncover the roots of Marnie’s trauma, Mark takes her to Baltimore to confront her mother, Bernice, during a raging thunderstorm—a symbolic echo of Marnie’s repressed memories. As tensions rise, the truth is finally laid bare: Bernice had once worked as a prostitute, and on a stormy night during Marnie’s early childhood, one of her clients had tried to comfort a frightened Marnie during the thunderstorm.

Mistaking the man’s intentions and believing he was trying to molest her daughter, Bernice attacked him. In the ensuing struggle, she fell and injured her leg, the wound that would leave her permanently disabled. In a moment of terror and confusion, young Marnie struck the man on the head with a fireplace poker, fatally wounding him. The traumatic scene—his blood (the source of her aversion to red), the thunder (her fear of storms), and the context of sexual tension became buried deep within her subconscious.

To protect her daughter, Bernice claimed responsibility for the man’s death, telling the authorities she had killed him and praying that Marnie would suppress the memory forever. But the psychological scars remained, shaping Marnie’s life of theft, lies, and emotional detachment.

Now, with the truth finally exposed and understood, Marnie breaks down and asks Mark for help. As dawn breaks over the storm, the two leave the house, holding each other closely, a glimmer of hope in their embrace as Marnie begins to face the possibility of healing.

Sean Connery plays the character Mark Rutland, a wealthy, intelligent, and emotionally complex widower who becomes fascinated. He serves as both a romantic lead and a psychological detective. His character drives much of the film’s plot, not just through romance or conflict, but through his insistence on uncovering the truth behind Marnie’s behavior—no matter the emotional cost.

Connery walks a fine line between being concerned lover and domineering husband. Connery handles this with seriousness and avoids melodrama, giving Mark psychological complexity rather than outright villainy. As Mark uncovers Marnie’s trauma, Connery’s performance becomes gentler and more empathetic. His calm demeanor helps balance the emotionally intense revelations.

Tippi Hedren plays role of Marnie Edgar, delivering a complex, emotionally intense performance that anchors the film’s psychological themes. Hedren had to navigate a broad emotional spectrum—fear, rage, vulnerability, detachment, and trauma. She depicts Marnie’s icy exterior and wounded interior with a compelling duality. Her face often masks a storm beneath the surface. Tippi Hedren’s role in Marnie stands as a milestone in psychological character study. She played a woman whose life is dictated by suppressed trauma, fear, and control.

The cinematography of Marnie, Robert Burks, is a significant component of the film’s psychological and emotional impact. Burks brought a distinct visual language to Marnie, one that supported the film’s exploration of trauma, repression, and psychological disintegration.

Marnie is famous for its symbolic use of color, especially red, which represents Marnie’s trauma. Burks used color saturation and lighting effects to intensify red when it appeared onscreen, such as in flowers, clothing, or blood, to visually cue Marnie’s panic or breakdowns. Hitchcock even instructed that the red be hand-painted onto certain frames in post-production for stronger emotional impact.

Many scenes, including horseback riding and cityscapes, were filmed using rear projection, giving the film an intentionally artificial look.

Burks used low-key lighting in many indoor scenes, particularly in Marnie’s mother’s house or during emotional confrontations to emphasize mystery, repression, and unease. Subtle use of shadows mirrors the emotional distance and fractured inner world of the characters.

The camera often tracks Marnie closely, mimicking a sense of surveillance or entrapment. Burks used slow zooms or tight close-ups to isolate Marnie visually, reinforcing her emotional isolation. High-angle shots are used sparingly but effectively to convey her vulnerability—especially in scenes like the thefts or the horse accident.

The cinematography in Marnie reflects Hitchcock’s shift into more overt psychoanalytic territory, and Burks visualized that with a bold, theatrical touch. The storm sequences, safe-cracking scenes, and Forio’s death are heightened by a combination of stylized lighting and emotionally charged framing that pulls viewers into Marnie’s fractured psyche.

George Tomasini editing was instrumental in shaping the rhythm, suspense, and psychological depth that define Hitchcock’s style. He helped structure the film’s non-linear psychological arc, integrating flashbacks, dreams, and subjective experiences with clarity and tension. He paced scenes like the safe thefts, storm breakdowns, and repressed memory flashback with restraint and increasing intensity. The slow, deliberate pace in parts of Marnie mirrors Marnie’s internal struggle and fragmentation, creating a dreamlike, almost surreal rhythm.

Bernard Herrmann‘s composition for Marnie is lush, haunting, and deeply emotional, matching the psychological intensity of the story. It uses rich strings, melancholic themes, and tense, dissonant passages to mirror Marnie’s trauma, repression, and evolving inner conflict. Unlike Psycho, where he used only strings for a harsh, stabbing effect, Marnie‘s score is more romantic and somber, underscoring the psychological undercurrents rather than the horror. The music builds empathy for Marnie, enhancing the film’s emotional impact even as her actions remain morally ambiguous.

Hitchcock’s direction in Marnie remains a masterclass in psychological filmmaking, blending stylized visuals with profound emotional resonance. It marked the cool, enigmatic female archetype — would take center stage in one of his films. He reportedly called Marnie a “close-to-the-heart” project, even more personal than some of his more commercially successful works.

Photos courtesy Google. Excerpts taken from Google.