Govindan Aravindan was a multifaceted Indian artist film director, screenwriter, musician, cartoonist, and painter widely regarded as one of the pioneers of parallel cinema in Malayalam.

G. Aravindan was the son of noted comedy writer M. N. Govindan Nair. Aravindan was also employed as an officer in the Rubber Board, where he became associated with artist Devan, playwright Thikkodiyan, and writer Pattathuvila Karunakaran. The influence of this circle can be seen in his early cinematic works, particularly in the spiritual undertones, which drew inspiration from satirist Sanjayan and the mystical visual style of painter K. C. S. Paniker.

He studied at University College, Trivandrum. Before entering the film industry, he had already made a name for himself as a cartoonist. He began his professional career as a cartoonist with the journal Mathrubhumi, gaining prominence in the early 1960s with his popular cartoon series Cheriya Manushyarum Valiya Lokavum. The series, centered on the characters Ramu and Guruji, cleverly blended political and social satire through their everyday encounters. After the series ended in 1973, Aravindan continued to contribute cartoons to various journals, though less frequently.

Aravindan’s directorial debut, Uttarayanam (1974), emerged as a collaborative effort with his creative circle produced by Pattathuvila Karunakaran and written by Thikkodiyan. The film, rooted in the spirit of Aravindan’s earlier cartoon series Cheriya Manushyarum Valiya Lokavum (“Small World and Big People”), critiques opportunism and hypocrisy against the backdrop of India’s independence movement. It follows the story of Ravi, an unemployed youth navigating a series of revealing encounters during his job search. As Ravi reflects on the sacrifices of freedom fighters stories he has heard from his paralyzed father he meets Gopalan Muthalaly, a former Quit India leader who has since become a corrupt contractor. Uttarayanam received widespread critical acclaim and won several accolades, including five Kerala State Film Awards, establishing Aravindan as a bold new voice in Malayalam cinema.

Aravindan’s second film, Kanchana Sita (1972), is a bold and meditative adaptation of C. N. Sreekantan Nair’s play of the same name a reinterpretation of the Ramayana’s Uttara Kanda. Widely credited with helping shape the new wave of independent filmmaking in Malayalam cinema, the film departs radically from traditional mythological portrayals. Set at the moment when Rama banishes Sita to appease his subjects, Aravindan’s version is deeply philosophical, infusing Samkhya-Yoga concepts especially the Prakriti–Purusha duality to explore the emotional and spiritual tensions within the epic’s characters.

From a feminist lens, Kanchana Sita stands apart by humanizing mythological figures like Rama and Lakshmana, presenting them with emotional fragility and moral complexity rather than divine infallibility. In a strikingly original move, Aravindan cast members of the Rama Chenchu tribe who consider themselves descendants of the mythic Rama as the leads. Shot in the remote tribal regions of Andhra Pradesh, this choice sparked controversy, with upper-caste Hindu groups accusing Aravindan of blasphemy. Unfazed, he defended the decision, citing the Chenchus’ classical features, rooted cultural presence, and naturalistic performances as integral to the film’s vision.

Aravindan’s next film, Thampu (1978), marked a turn toward stark realism, portraying the hardships and emotional struggles of a traveling circus troupe. Shot in black and white with a direct, documentary style approach, the film emphasized observational storytelling over dramatic structure. Its minimalist aesthetic and poignant depiction of transient lives earned Aravindan widespread acclaim. He was awarded Best Director at both the National Film Awards and the Kerala State Film Awards, further cementing his reputation as a visionary of parallel cinema.

Aravindan’s 1979 films Kummatty and Esthappan explore entirely different narrative terrains, each reflecting his experimental approach to storytelling. Kummatty, inspired by Malabar folklore, revolves around a Pied Piper-like figure part magician, part bogeyman who enchants village children before vanishing as mysteriously as he appeared. The film weaves myth with reality, crafting a magical realist tapestry deeply rooted in oral traditions.

In contrast, Esthappan draws allegorical parallels with the life of Christ, centering on its titular character whose cryptic actions and elusive presence intrigue and unsettle his coastal community. Through Esthappan’s story, Aravindan probes themes of faith, collective memory, and the construction of myth within a distinctly local and spiritual context.

Aravindan’s next film, Pokkuveyil (1981), delved into the indefinability of the human mind. The film was created without a conventional script; legend has it that its visuals were composed based on musical notations by renowned flautist Hariprasad Chaurasia, who also composed the score. The film follows a sensitive young artist whose world gradually unravels his father dies, his radical friend disappears, his athlete friend is paralyzed in an accident, and the woman he loves is taken away by her family. The protagonist, portrayed by poet Balachandran Chullikkadu, drifts into isolation, mirroring the film’s meditative and impressionistic tone.

Chidambaram (1985) marked a pivotal moment in Aravindan’s career, showcasing his continued evolution as a filmmaker of profound sensitivity and restraint. Adapted from a short story by C. V. Sreeraman and produced under his own banner, Suryakanthi, the film unfolds against the tranquil backdrop of a cattle farm nestled in the hilly borderlands between Kerala and Tamil Nadu. Within this serene setting, Aravindan explores the intricate dynamics of human relationships particularly between men and women while delving into deeper themes of guilt, desire, betrayal, and the possibility of redemption.

Featuring a powerful cast that includes Bharath Gopi, Smita Patil, Sreenivasan, and Mohan Das, Chidambaram is grounded in a naturalistic performance style that heightens its emotional and moral complexity. The film’s layered storytelling, meditative pacing, and quiet intensity earned widespread acclaim, and it is widely regarded as one of Aravindan’s most mature and introspective works an embodiment of his uniquely contemplative cinematic voice.

Aravindan’s Oridathu (1986) can be seen as a thematic extension of his earlier film Thampu and his long-running satirical cartoon series Cheriya Manushyarum Valiya Lokavum (The Small Man and the Big World). Set in a rural Kerala village in the 1950s, the film centers on the disruption caused by the arrival of electricity a symbol of modernity that ironically brings more chaos than progress. Though electricity is conventionally associated with development, Aravindan’s narrative leads to the poignant conclusion that life, in some respects, was simpler and more harmonious without it.

Aravindan described this stylistic choice as deliberate: “There is an element of caricature in all the characters. A little exaggeration and a lot of humour was consciously introduced to make effective the last sequence, which is the explosion.” The film steadily builds towards this climax an explosive clash during a festival that serves as both literal and symbolic breakdown.

Oridathu features a sprawling ensemble cast and an episodic structure, eschewing a central protagonist in favor of a mosaic of characters and events. This democratic storytelling mirrors the complexity of village life, presenting a community in flux.

A conventional music score, Aravindan emphasizes ambient sounds natural, mechanical, and human to ground the story in its lived environment. The film also foregrounds Kerala’s linguistic diversity: villagers speak the pure Valluvanadan dialect of South Malabar, the government overseer uses Trivandrum Malayalam, and the fraudulent doctor employs Travancore Malayalam. These distinctions subtly underscore regional identities and class dynamics, enriching the film’s cultural texture.

Aravindan also worked on several documentaries and short films, expanding his creative pursuits beyond feature cinema. He composed music for critically acclaimed films such as Aaro Oral, Piravi, and Ore Thooval Pakshikal, showcasing his versatility as an artist. In 1989, he directed Unni, an international co-production loosely inspired by the real-life experiences of a group of American students in Kerala, who portrayed themselves in the film.

Aravindan’s final feature film, Vasthuhara (1991), marked a poignant end to his cinematic journey. Based on a short story by C. V. Sreeraman, the film explores the lives of refugees in Bengal and their struggles with displacement and identity. Vasthuhara featured celebrated actors Mohanlal and Neena Gupta in major roles and is often remembered for its sensitive portrayal of human suffering and resilience.

G. Aravindan’s work as a director left an indelible mark on Indian cinema, particularly Malayalam cinema, where he became one of the pioneers of parallel cinema. His films, known for their unorthodox narrative styles and exploration of complex human themes, such as societal issues, identity, and spirituality, are celebrated for their depth, simplicity, and socio-cultural reflections. From Uttarayanam (1974) to Vasthuhara (1991), Aravindan consistently pushed boundaries with his unique visual storytelling, using non linear narratives and minimalistic styles to explore the essence of human experience.

Aravindan’s musical contributions further enriched his films. He composed music for several projects, including Aaro Oral, Piravi, and Ore Thooval Pakshikal. His understanding of music as a storytelling tool allowed him to use sound and silence as integral elements of his cinematic expression, making his films resonate on both emotional and intellectual levels.

To honor his legacy, the Kerala Chalachitra Film Society established the Aravindan Puraskaram, an annual award for the best debutant director in Indian language cinema, celebrating emerging talents who continue to carry forward Aravindan’s commitment to innovative, thought provoking filmmaking.

In recognition of his contributions to Indian arts and cinema, the Government of India honored him with the Padma Shri, the country’s fourth highest civilian award, in 1990.

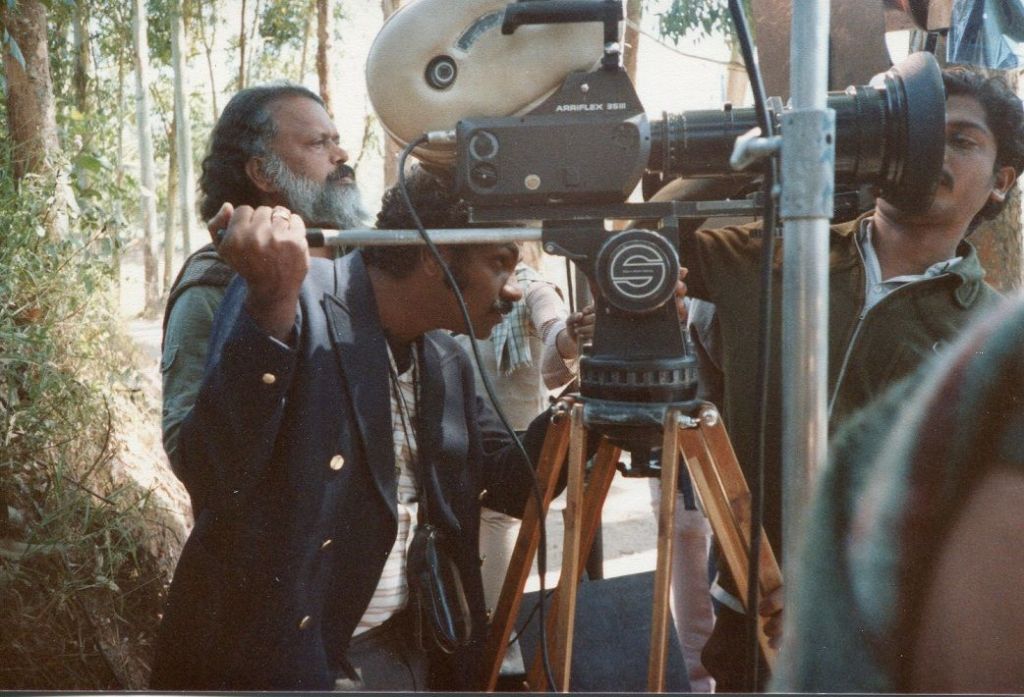

Photos courtesy Google. Excerpts taken from Google.