Kummatty (1979), directed by the Malayalam filmmaker G. Aravindan, is considered a landmark in Indian children’s cinema. Ramunni, Master Ashok and Vilasini Reema were cast in the film.

Film based on a folktale from the Malabar region of Kerala, Kummatty tells the story of a pied-piper-like magician who possesses the uncanny ability to transform children into animals. The director seems to anticipate curiosity and skepticism mirroring it in the children themselves.

The film opens with the sun rising over the mountains, unveiling the brownish green landscape and fresh skies of a quiet hamlet, while a man’s song gently plays in the background. Aravindan captures rural life with lyrical beauty serene, idyllic, and tinged with innocence, playfulness, and subtle tension. The peaceful routines of the young boy, Chindan, are gradually contrasted with the mysterious, almost mythical presence of Kummatty, whose arrival shifts the tone from the ordinary to the enchanted.

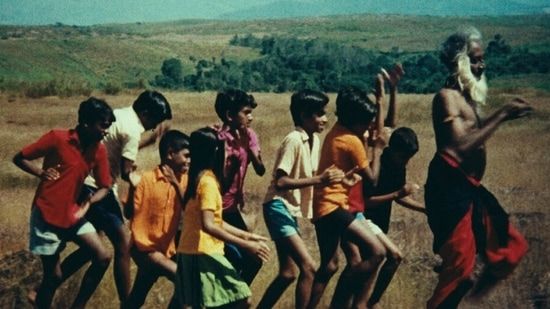

The children are utterly enchanted by Kummatty. When he appears midway through the school day, they abandon their classrooms without hesitation, flocking to him in pure delight. They form a circle around him as he sings his timeless songs, again and again. Kummatty has no home, no family. He is a wanderer, who sleeps under an old tree, cooks modest meals over a small pot, and carries his few belongings in a sack. His presence, while magical, is fleeting. When he announces that it is time for him to leave, the children plead with him to stay. He offers them one final magic trick, a parting gift that seems innocent at first he casts a spell that transforms each child into the animal represented by the mask they wear. A monkey, a cow, an elephant each transformation is playful, and joyous. Chindan, transformed into a dog, is overjoyed, bounding with excitement through the open fields. But when Kummatty begins to reverse the spell, Chindan is nowhere to be found. In that missed moment, Aravindan’s film takes a sudden, surprising turn shifting from gentle folklore to something deeper and more mysterious, as Chindan’s fate becomes the emotional and philosophical heart of the story.

Still trapped in the body of a dog, Chindan walks into captivity, lured by the affection of a girl who takes him home as a pet, only to be chained, bathed alongside the household dog, and treated not as a child but as an object. Unable to accept this new life, he escapes and returns to his village, where in a profoundly touching moment, his mother instantly recognizes him despite his animal form and treats him with the same love and care, feeding him from the same plate as before. For a year, he lives in this suspended state between enchantment and reality until one day Kummatty returns. The moment the dog runs to him, Kummatty immediately recognizes Chindan and lifts the spell, transforming him back into a boy.

The final scene, where Chindan releases a parrot into the open sky, becomes a powerful metaphor for liberation and renewal. Just as he has been freed from his physical and spiritual confinement, the bird’s flight symbolizes the reclaiming of identity and the unbounded possibilities of life. The earlier image of the caged bird contrasts strikingly with this moment, highlighting a journey from restriction to release. As the birds soar in different directions, the film gently affirms the beauty of freedom, the resilience of the human spirit, and the quiet, mythic wonder that defines Kummatty’s poetic and profoundly hopeful conclusion.

Aravindan constructs a poetic cinematic landscape in which illusion and reality coexist, transforming the ordinary through collective imagination and quiet magic. Grounded initially in the rhythms of rural life its fields, classrooms, myths, and social rituals the film gently draws viewers into a dreamlike state where belief becomes second nature. Without relying on special effects or spectacle, Aravindan achieves timeless enchantment through a restrained, lyrical aesthetic that invites both children and adults into a shared suspension of disbelief. As Chindan’s transformation unfolds, so too does a deeper narrative about captivity and freedom, class and compassion, speaking subtly yet powerfully to broader human truths.

The interaction between Chindan and the old woman sweeping the temple floors captures how Kummatty blends childhood mischief with the eerie undertones of folklore. Chindan’s playful whisper of “Kummatty” hints at the myth’s grip on the village imagination. As the boys follow men discussing a woman’s illness, they begin to witness the blurred line between myth and reality. The ritualistic healing scene, where a doctor attempts to extract “negative energy,” deepens the film’s mystical mood, revealing a world where superstition and everyday life are inseparable, and where children slowly awaken to its complexities.

The scene where Chindan teases the old woman by whispering “Kummatty” captures the film’s blend of childhood playfulness and the village’s deeper, mythic fears. This innocent act hints at the powerful presence of folklore in everyday life. As Chindan and his friend follow men discussing a woman’s illness, they begin to glimpse the adult world’s mysteries. The ritualistic healing that follows, with a doctor extracting “negative energy,” further blurs the line between reality and superstition, revealing a community shaped by belief systems that transcend logic.

The film, through its rich symbolism and blend of fantasy with realism, explores the concept of childhood transformation, both magical and emotional, and the consequences of curiosity, innocence, and even the harshness of reality.

As a director, G. Aravindan didn’t use music merely as an embellishment, but as a narrative voice. The compositions by M.G. Radhakrishnan and Kavalam Narayana Panicker were likely conceived in deep conversation with the visual and thematic elements of the film. The composers to capture the earthiness of the Malabar landscape using folk rhythms, natural sounds, and melodic simplicity. Aravindan would use these musical motifs not just to announce Kummatty’s presence, but to define him mysterious but not threatening, magical yet grounded in human warmth.

The music in Kummatty is not decorative it is part of the film’s spiritual essence. As a director, the music subtly reinforces the themes of transformation, freedom, nature, and the loss and return of innocence. This collaboration with the composers is less about instructing and more about tuning into the film’s spirit. A director’s point of view, music in Kummatty becomes a silent character, a bridge between the real and the mythical, between the seen and the felt.

The cinematography of Kummatty by Shaji N. Karun is not just a technical achievement it’s a poetic extension of the film’s soul. Karun paints the village not as a backdrop but as a breathing, living character. The brownish greens, sunrises, and misty fields feel elemental enhancing the story’s folklore quality. His use of natural light and diffused colors reflect Aravindan’s contemplative style: slow, immersive, and meditative.

Kummatty is seen from Chindan’s point of view, his curiosity, fear, and wonder. Karun’s camera crouches low, follows with distance, or frames Chindan in the wide expanse of nature, emphasizing how small yet vibrant a child’s world can be. Kummatty transforms the children into animals, there’s no special effects spectacle only visual suggestion. The camera’s restraint becomes more powerful than CGI. Soft focus, rhythmic pans, and juxtaposition of faces and masks convey transformation as a mystical experience, not an illusion.

Kummatty, edited by Ramesan Anand, flows with a lyrical and dreamlike rhythm that complements Aravindan’s vision, enhancing the film’s seamless blend of realism and fantasy.

The brilliance of Kummatty caught the attention of legendary American filmmaker Martin Scorsese, who played a key role in the film’s restoration through the Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project, a program he founded in 2007 to preserve and showcase global cinematic treasures. In collaboration with the Film Heritage Foundation and Italy’s Cineteca di Bologna, the project brought renewed life to Aravindan’s visionary work. Sharing a still from the film on his Instagram, Scorsese praised Kummatty as “a sweet and engaging story” and “visually stunning,” strongly recommending it as “a must see,” thus reaffirming the film’s place in the world cinema canon.

Aravindan and Shaji N. Karun achieve this union, visual storytelling that evokes emotion through patience, silence, and sensory immersion making Kummatty feel less like a film and more like a fable remembered from childhood.

Photos courtesy Google. Excerpts taken from Google.