Taxi (also known as Taxi Tehran) is a 2015 Iranian docufiction film written, produced, edited, and directed by and starring Jafar Panahi. Despite being banned from filmmaking and travel by the Iranian government in 2010, Panahi secretly made this film by placing a camera inside a taxi he drives around Tehran, capturing conversations with various passengers.

In Taxi, director Jafar Panahi turns a regular taxi ride through Tehran into a way to explore life in Iran. Pretending to be a taxi driver, he picks up different passengers, each with their own stories and views. He doesn’t take any money from them because he’s not really driving for work, he just wants to listen and understand people. The taxi becomes a small world where we see different sides of Iranian society.

The film’s first encounter sets the tone for the social and moral discussions that follow. Panahi picks up a man and then a woman who are headed in the same direction. As they begin to talk, their conversation quickly turns into a debate about crime and punishment in Iran.

The man, who later hints that he works as a hired mugger, strongly supports the use of capital punishment. He believes that hanging criminals under Sharia law would scare people into behaving properly. To him, fear is the best way to control crime.

The woman, however, disagrees. She takes a more compassionate and thoughtful view, arguing that the government should look deeper into why people commit crimes, especially poverty and social inequality. This early scene introduces one of the film’s key themes: the clash between harsh punishment and human empathy in the face of real-life struggles.

Next, Panahi picks up Omid, a small-sized but lively DVD seller who deals in banned international films. His cheerful and clever nature is similar to a media seller in Mohammad Rasoulof’s Head Wind (2008). Omid recognizes Panahi and reminds him that, like Panahi, he is also helping to spread culture by secretly giving people access to films they can’t see otherwise.

Panahi then picks up a seriously injured man who was in a motorcycle accident, along with his worried wife. On the way to the hospital, the man, fearing he might die, urgently asks for his last will to be recorded on a phone. He wants to make sure his wife inherits his possessions, since under current law, everything would otherwise go to his brothers, leaving his wife with very little. This emotional scene highlights both the fragility of life and the legal inequalities faced by women in Iran.

Next, Panahi picks up two middle-aged women carrying a bowl of goldfish. They believe, out of superstition, that they must release the fish into Ali’s Spring in South Tehran before noon, or else something bad will happen to them. Their urgency and belief in this ritual add a touch of humor and absurdity to the film. While this scene may not point to a specific social issue, it reflects the blend of faith, tradition, and everyday anxiety that shapes some people’s lives and the kind of quirky encounters taxi drivers often experience.

Panahi picks up his niece, Hana, from school. On the ride home, she excitedly shares her school assignment to make a short film using her cell phone camera. However, her teacher has given strict guidelines to make the film “distributable,” meaning it must follow government rules. These include: respecting the Islamic dress code, no male-female contact, no realism, no violence, no neckties or Iranian names for heroes, and no mention of political or economic issues. While Panahi knows these restrictions well, he lets Hana talk about them with childlike honesty, subtly exposing the limits placed on creativity in Iran.

Panahi meets his old neighbor, Arash, who shows him CCTV footage of a recent robbery where he was mugged by masked men. Although Arash wants to talk about the incident, he’s hesitant to report the thieves. He secretly recognized them and knows they are poor and desperate. Arash fears that if they are caught and prosecuted, they might face execution. This moment highlights the moral dilemma between seeking justice and showing mercy in a harsh legal system.

Meanwhile, Hana ends up filming a moment that might be seen as siahnamayi herself. She captures a boy picking up money that fell from a newly married couple. At first, he refuses to return it, showing a lack of honesty. This simple scene reflects the kind of real-life situation that might be considered too negative under censorship rules, even though it’s a true and meaningful observation.

Panahi’s last passenger is Nasrin Sotoudeh, a well-known human rights lawyer and his old friend. She’s on her way to visit Ghoncheh Ghavami, jailed for trying to attend a men’s volleyball match—echoing Panahi’s film Offside. Sotoudeh explains that Ghavami has begun a hunger strike after 100 days in solitary confinement, reminding Panahi that both of them had also used hunger strikes during their unjust imprisonment.

Sotoudeh’s own story reflects her courage, she was arrested in 2010, sentenced to 11 years, and banned from practicing law for defending human rights cases. After spending three years in prison, she was released in 2013. Her brief appearance in Taxi reinforces the film’s powerful message about resistance, justice, and free expression under repression.

Before leaving, she gives Panahi a rose as a symbol of support and encouragement for filmmakers like him who continue working despite restrictions.

After dropping off Nasrin Sotoudeh, Panahi drives to Ali’s Spring to return the forgotten purse to the woman with the goldfish bowl. In the film’s tense final scene, which lasts over four minutes, Panahi and his niece Hana leave the taxi to look for her. While they’re gone, a man—likely a Basiji thug (linked to Iran’s paramilitary forces)—approaches the empty cab, enters, and destroys the dashboard camera, clearly searching for the recorded footage.

However, he fails to find the flash drive, which Panahi had wisely taken with him. This subtle but powerful ending underscores the constant threat of surveillance and censorship in Iran, while also celebrating Panahi’s quiet defiance and clever resistance.

Just as this good deed is completed, the mood shifts. A pair of unknown men possibly thieves or government agents, suddenly break into the taxi and ransack it. Before viewers can understand what happens next, the film abruptly cuts off. This sudden ending serves as a powerful reminder of the constant threat Panahi faces for his defiance, and the fragile balance between hope and repression in Iran.

Taxi not only tells personal stories but also reflects the broader social issues in today’s world. In the film, Jafar Panahi plays a taxi driver navigating the streets of Tehran, picking up a variety of passengers, each with their own unique backgrounds and views. Through their conversations, the film quietly explores topics like justice, poverty, censorship, and human rights.

All the scenes are shown from inside the taxi using dashboard-mounted cameras and mobile phone cameras held by some characters. This limited but creative setup makes the film feel intimate and real, almost like a documentary. Despite these constraints, the film feels rich and engaging.

Surprisingly, the entire film—from shooting to editing—was completed in just fifteen days. This fast and efficient production shows Panahi’s resourcefulness and deep commitment to making films, even under heavy government restrictions and with very limited resources.

Jafar Panahi played several major roles in Taxi, making it a truly personal and independent project. As director, he crafted the film’s unique style—using the setting of a taxi ride to explore everyday conversations that reveal deeper social and political issues. His direction makes the film feel natural and spontaneous, even though it was carefully thought out.

As the producer, Panahi worked completely outside the state-run film system, which was essential since he was officially banned from making films. This independence gave him full creative freedom, allowing him to tell the story he wanted without censorship.

He also came up with the story and structure. Though it feels improvised, the film was subtly planned, with each conversation serving a purpose. Panahi used real-looking situations and characters to reflect Iranian society, blurring the line between documentary and fiction.

Panahi also stars in the film, playing himself as a taxi driver. His quiet presence, listening more than speaking, makes space for the stories of his passengers while also subtly expressing his own resistance and empathy.

Through all these roles, Jafar Panahi made Taxi not just a film, but an act of creative defiance, highlighting the power of storytelling even under heavy restrictions.

Banned from making movies by the Iranian government, Jafar Panahi poses as a taxi driver and makes a movie about social challenges in Iran. His two earlier films during the ban were shot in secret one inside his apartment (This Is Not a Film) and the other in a private home (Closed Curtain). But with Taxi, Panahi took a bold step by filming openly on the streets of Tehran, using the setting of a taxi to avoid drawing too much attention.

After the film was announced to premiere at the Berlin International Film Festival, Panahi released a powerful statement reaffirming his commitment to filmmaking. He declared that no restrictions could stop him from creating, saying, “Nothing can prevent me from making films since when being pushed to the ultimate corners I connect with my inner-self and, in such private spaces, despite all limitations, the necessity to create becomes even more of an urge.” His words reflect both resilience and the deep personal need to express himself through cinema, no matter the risks.

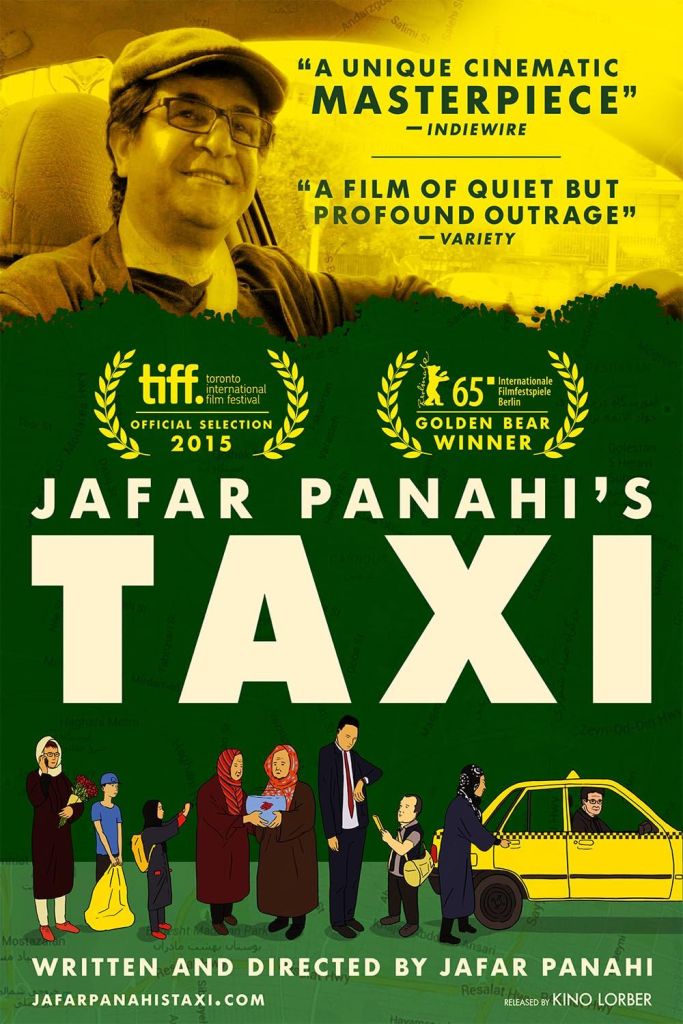

The film Taxi premiered in competition at the 65th Berlin International Film Festival on February 6, 2015. Despite Jafar Panahi’s ban from filmmaking and international travel, the film received widespread acclaim and went on to win the Golden Bear, the festival’s top prize. Since Panahi couldn’t attend due to his ban, his young niece, Hana Saeidi, who also appears in the film, accepted the award on his behalf.

The film received strong critical acclaim. The website’s critical consensus reads: “Jafar Panahi’s Taxi offers another round of trenchant societal commentary from a director whose entire filmography stands as a daring act of dissent.” This highlights how Panahi continues to challenge authority through his films.

Berlin International Film Festival Jury President Darren Aronofsky praised the film, calling it “a love letter to cinema… filled with love for his art, his community, his country, and his audience.” His words reflect the emotional and artistic depth of Taxi, as well as Panahi’s courage and dedication to filmmaking despite severe restrictions.

Photos courtesy Google. Excerpts taken from Google.