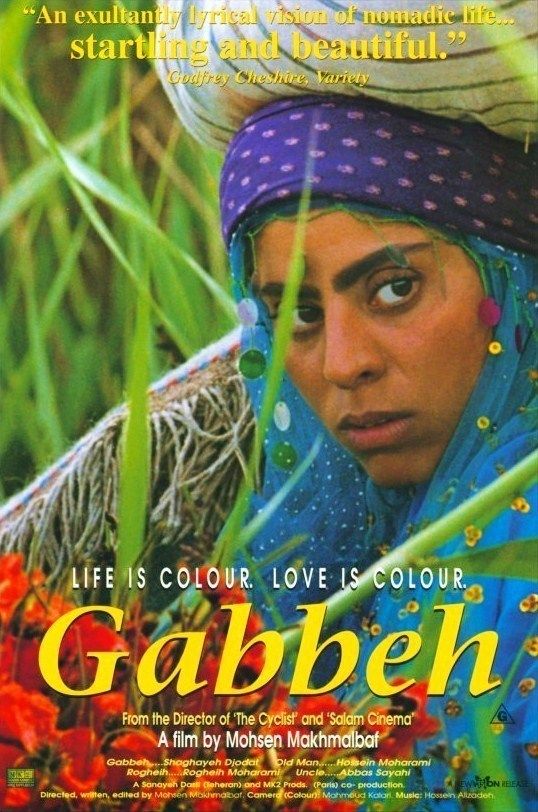

Gabbeh is a 1996 Iranian film directed by Mohsen Makhmalbaf.

The film takes its name from a type of Persian rug known as a gabbeh. It begins with an elderly couple walking toward a river, carrying their gabbeh, hoping to wash it. When they spread the rug on the ground, a young girl, called Gabbeh, magically emerges from it. The film then follows her story, introducing her family, her uncle who is searching for a bride, and, most importantly, her deep longing for a young man she hopes to marry.

The story begins with an eccentric old couple making their way down to a river to wash one of their prized possessions, a Persian rug known as a gabbeh. The old man (Hossein Moharami) is a chronic complainer, speaking in a strange sing-song tone that some may find endearing, while others might find irritating though the film eventually reveals a reason for his peculiar manner. His wife (Rogheih Moharami) is more grounded, with a quiet sense of humor, but it soon becomes apparent that her grasp on reality has gradually slipped over the years.

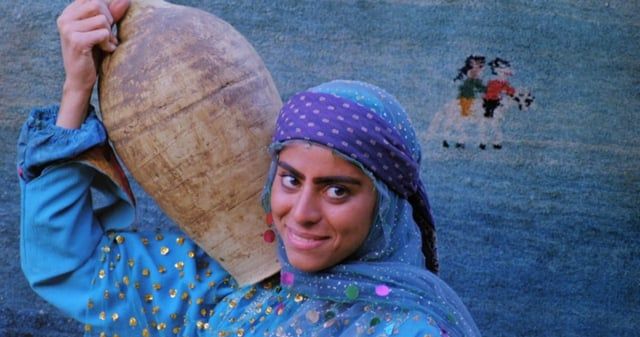

The pattern woven into their rug tells a story, and as the rug is immersed in the water, a mysterious and beautiful young woman (Shaghayeh Djodat) emerges from it. She begins to recount her own tale, which becomes intertwined with the story depicted on the rug and, eventually, with the lives of the old couple themselves. What follows are two interconnected stories told in flashback, both centered on love and the search for the ‘right’ partner.

One of the stories follows a middle aged man (Abbas Sayah), known simply as ‘Uncle’, who returns to his nomadic roots among the Qashqai tribes of Iran after failing to find love in the city. His homecoming is marked by a quiet sorrow during his absence, his mother passed away, leaving behind an unfinished rug still resting on her loom, a poignant symbol of interrupted life and unfulfilled hopes.

He dreams that he will find his future wife by a spring, singing like a canary and sure enough, he comes across a woman washing pans at a spring, singing a song she has made up herself. He’s so moved by her poem that he feels inspired to compose one of his own. It begins, “Looking is not seeing, Behind every cradle there is a grave, Behind every joy, sadness…” and ends with, “My body is like a cold, silent dungeon, But my heart is like a happy child.” She likes his poem so much that she agrees to accept him as her suitor. His sadness turns into happiness, and it seems their love story will have a joyful ending.

One of the younger girls in the family who we realize is the same mysterious girl from the gabbeh doesn’t find love so easily. She’s in love with a mysterious horseman, even though they’ve never met. She only sees him from a distance, and he follows a trail of scarves she leaves for him. At night, he howls like a wolf to let her know he’s nearby. But her father won’t let her marry until she finishes weaving the gabbeh her grandmother started. When she finally finishes it, he keeps making new excuses to stop her from marrying the horseman. Their love story starts to take a more tragic turn or so it seems.

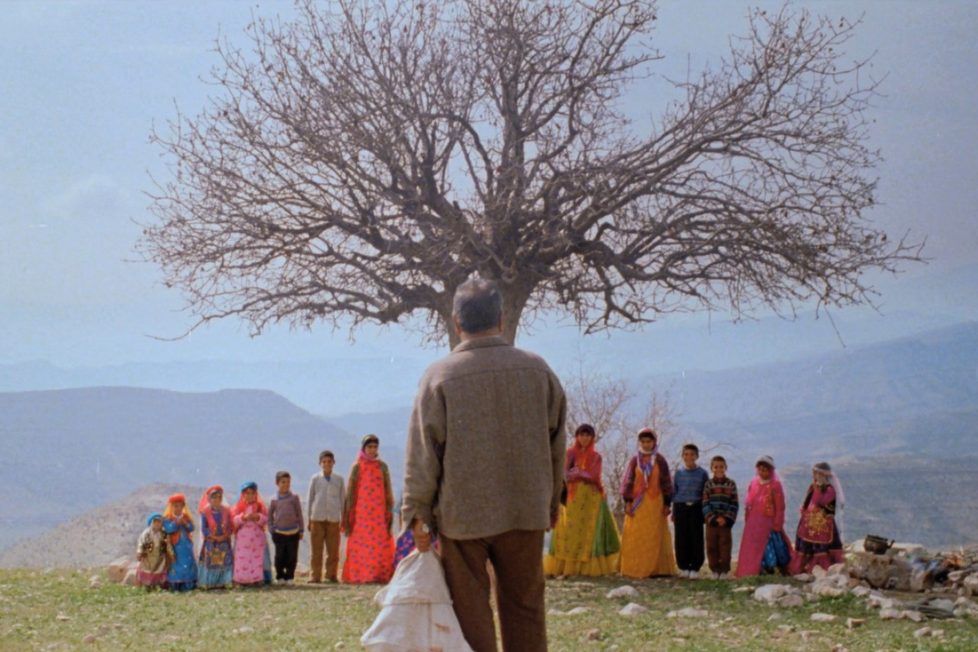

As ‘Uncle’ approaches a yurt, he hears children reciting their times tables. Inside, boys and brightly dressed girls are learning together. He interrupts to give a lesson of his own more poetic and magical. Pointing to red flowers, he suddenly holds them. Yellow blooms appear the same way. He gestures to the sky his hand turns blue. He reaches for the sun it turns golden.

Through simple cuts and montage rather than special effects, this scene creates a sense of magic that feels both meaningful and lasting. When Uncle says, “Color is life,” it sets the tone for the rest of the film and the entire trilogy. His teaching is poetic—he draws colors from the world around him: red from a meadow, yellow from a field, blue from the sky, and gold from the sun. The scene’s quiet beauty lies in its simplicity, using clever editing to transform everyday moments into something profound.

The women wear bright clothes that stand out against plain backgrounds, making each shot look like a flat tapestry, like the gabbeh rugs. In one scene, the tribe walks through soft-colored landscapes with gabbehs laid out to dry. The wool comes from the sheep, the colors from flowers and plants, and the stories from the people. These stories are woven into the rugs, turning real lives into folktales.

In Gabbeh, the young woman is a mysterious, ethereal figure who appears to step out of a gabbeh rug. She represents both a character in the rug’s story and a symbol of longing, love, and the spirit of the nomadic people. She appears to step out of a rug showing her and a horseman, and she shares a tale of love, longing, and waiting for her father’s approval to marry.

The aged man, known simply as ‘Uncle’, is a wise, poetic figure who introduces the theme of color with the line “Color is life.” He serves as a guide, both literal and metaphorical, connecting the physical beauty of nature with the deeper emotional and artistic layers of the story. Uncle’s presence helps frame the narrative as a blend of memory, myth, and tradition.

Director Makhmalbaf draws on the splendor of nature vast deserts, open skies and the human use of color to create a visually rich experience. In one memorable scene, the old uncle names different colors, and they magically appear on screen. In other scenes, wildflowers used for natural dyes connect the beauty of the landscape directly to the art of rug-making.

Gabbeh is a colorful and romantic tribute to beauty, nature, love, and art. Director Mohsen Makhmalbaf first set out to make a documentary about the Qashqai and Bakhtiari nomads of Iran, known for weaving vibrant gabbeh rugs that tell personal stories. Inspired by the striking landscapes and the meaning behind the rugs, he turned the project into a surreal love story.

Through Mahmoud Kalari’s rich cinematography, the gabbeh becomes a magical thread that weaves together past and present, fantasy and reality. The Silence and Gabbeh have been beautifully restored from the original camera negatives. The restoration teams have done an excellent job, preserving the delicate pastel tones while enhancing vivid saturation and achieving a smooth tonal gradient throughout no small feat given the challenging, sun-drenched visuals. In The Silence, a few shots have slightly washed out colors, but it feels intentional and doesn’t detract from the film’s overall visual charm.

Gabbeh is a masterclass in slow, confident visual storytelling, a film that could be understood even without subtitles. Its gentle pacing, lyrical imagery, and structure feel more like music than a traditional plot, with recurring motifs, the rhythm of weaving, and the cycle of life. Gabbehs themselves, with their soothing, childlike designs, are deeply rooted in the land and labor of nomadic life from the herder’s wool to the colors gathered by young girls in the fields. Yet few Iranians today own or even know of gabbehs, despite their rich cultural heritage. As one voice in the film reflects, a carpet is more than just wool and color it is the story of a people, and Gabbeh beautifully brings that story to life like a poetic fable.

It was screened in the Un Certain Regard section at the 1996 Cannes Film Festival. The film was also selected as Iran’s official entry for the Best Foreign Language Film at the 70th Academy Awards, although it was not nominated.

Gabbeh received critical acclaim at several international film festivals. At the 1996 Sitges Film Festival, it won both the Best Director award and the Special Critics Award. It also received the Silver Screen Award at the Singapore International Film Festival and the Best Artistic Contribution Award at the Tokyo International Film Festival. Additionally, the film was recognized by The Times (USA) as one of the ten best films of 1996, further cementing its status as a visually poetic and emotionally resonant work.

Photos courtesy Google. Excerpts taken from Google.