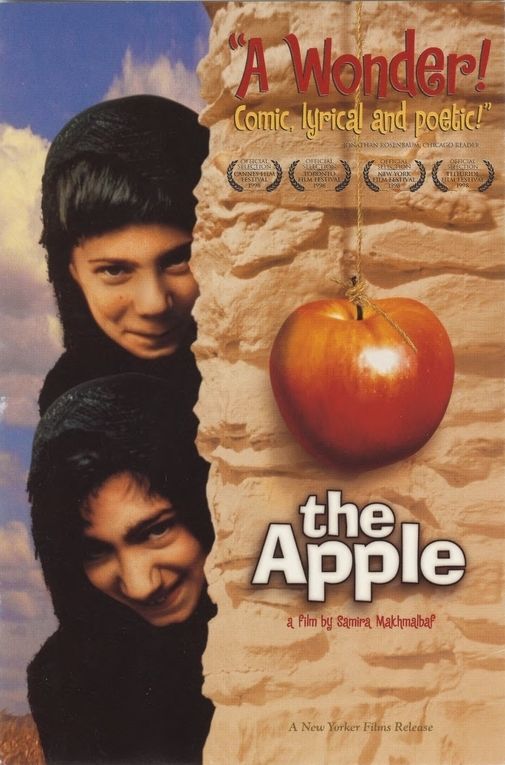

The Apple is a 1998 Iranian film that marked the directorial debut of Samira Makhmalbaf, the daughter of well-known Iranian filmmaker Mohsen Makhmalbaf. The film is based on a true story and is unique because it features the real people involved in the events, rather than professional actors. This gives the film a documentary-like feel, blending fiction and reality.

The Apple tells the true story of the Naderi family in Tehran, 12-year-old twin sisters, Massoumeh and Zahra have been confined to their home since birth by their overprotective father and blind mother. The father defends his actions, claiming, “My daughters are like flowers. They may wither with the sun.” However, when a concerned social worker intervenes, a quiet battle begins between tradition and change, as the world outside starts to beckon the girls toward freedom.

The twin girls are kept away from modern life and shown as quiet victims of many kinds of control. Zahra and Massoumeh Naderi are locked behind a metal-barred door, with no contact with other people. This has left them unable to walk or talk like other children. But they do speak to each other and to their parents, sharing a private world of girlhood that belongs only to them. The film gives a rare and powerful view of two girls growing up not by telling a sweet or dreamy story, but by showing their real experience. Unlike many American films that make childhood look perfect, The Apple is honest and raw. It shows their life of being trapped, how strong they are, and how they slowly begin to wake up to the world.

The story becomes even more moving because the mother, who is always in the background, is blind and wears a full chador. The parents’ choice to keep their daughters inside for twelve years is questioned when neighbors complain to social services. A social worker visits and tries to convince the family to let the girls go outside and see the world. The film looks at the conflict between the parents’ traditional beliefs and modern ideas about freedom. The father is afraid his daughters will meet boys, which he sees as a threat. Nearby, boys are shown playing, and when their ball falls into the girls’ courtyard, it becomes a powerful symbol of the outside world they are missing. What makes it even more touching is that the real family plays themselves in the film, re-creating their own story.

Although the film starts with real events, it goes beyond just showing facts. It explores the emotions and thoughts of the family. The parents speak about what they believe, but the twin girls stay mostly silent. Instead of words, we understand their feelings through their small actions, looks, and reactions. This quiet and caring style gives their experience a deep and lasting emotional impact.

The neighbors think the father is being cruel and controlling. In an important talk with the social worker, he says he is only trying to protect his daughters from the outside world—especially from men. His thinking is shaped by fear and strict traditional beliefs. But instead of showing him as just a bad person, director Samira Makhmalbaf takes a more thoughtful view. She doesn’t excuse what he does, but she tries to understand it. The film shows the reasons behind his actions and makes the audience think about the cultural and social pressures that influence him.

Before freeing the girls, the social worker gives each of them a mirror and a comb to share simple objects that carry quiet yet powerful symbolism. The mirrors, in particular, are more than practical tools; they symbolize self-awareness, personal identity, and the emergence of individuality. For the twins, who have spent most of their lives isolated from the outside world, these items mark the beginning of seeing themselves not just physically, but as separate, autonomous beings.

Director Samira Makhmalbaf explained the choice by saying, “Everybody uses mirrors, but women more than men. Women look in the mirror and find themselves.” In this context, the mirrors are more than tools for grooming—they become instruments of self-recognition. For the twins, they represent a chance to begin seeing themselves as individuals, not merely as daughters hidden away from the world. It’s a gentle yet powerful gesture, marking the first step toward self-discovery, freedom, and the formation of a personal identity that had long been denied to them.

Some of the most touching moments in The Apple are the scenes where the girls interact with other children. These moments highlight how different their lives have been. They meet a boy selling ice cream, watch neighbors’ boys climb the wall to get their ball, follow a boy into the city using a jug on a string, and later learn to play with other girls played by their real-life cousins. These scenes show the girls’ first steps into the modern world of childhood, re-enacted as a kind of remembered reality. As Reza Sadh notes, children often bring spontaneity to films by simply being themselves in everyday settings.

However, the girls are soon returned to their parents with a clear warning: they must not be locked up again. Despite this, the father once more confines the twins. When the social worker played by Azizeh Mohamadi finds them imprisoned again, she frees the girls and, in a striking reversal, locks the father inside the house.

The film also reveals that the twins had long harbored a quiet curiosity about the world beyond their confinement. Even before their release, they showed subtle signs of hope and imagination pressing their handprints on a wall inside the house or reaching out to water a plant just beyond their grasp. These small acts hint at a deep longing for connection and growth, making their first steps into the outside world all the more poignant and meaningful.

In The Apple, Zahra Naderi plays one of the twin daughters who have been locked inside their home for 12 years. Along with her sister Massoumeh, Zahra experiences the outside world for the first time when authorities intervene. Her role reflects the emotional and developmental impact of isolation, as she slowly learns to interact, speak, and explore freedom.

Ghorbanali Naderi, their real-life father, plays himself in the film. He is portrayed as the man who, out of fear and misguided beliefs, keeps his daughters imprisoned, convinced that he is protecting them. His character raises important questions about control, parental responsibility, and social neglect.

John Mount praises Samira Makhmalbaf’s kind and balanced approach, saying she avoids blaming anyone directly. Although the social worker frees the girls, they are not ready for the sudden change. Mount writes that seeing the twins stumble out “like liberated battery hens” shows how confused and unready they are for the outside world. It’s a powerful image of their fear and vulnerability.

The shift from video to 35mm film, along with poetic shots and a title sequence styled as a petition, marks a move from a news-like tone to a more cinematic one. While based on real events, The Apple goes deeper, exploring the emotions of the family. The parents speak for themselves, but the silent daughters must be understood through their gestures and expressions.

The film is a powerful and quietly emotional exploration of freedom, control, and the transition from isolation to independence made all the more impactful by the use of real people playing themselves.

The Apple was directed by Samira Makhmalbaf, who was only 17 years old when she made the film. As the director, she was in charge of the film’s artistic vision—how the story was told through images, performances, and camera work.

The screenplay was a collaboration between Samira and her father, Mohsen Makhmalbaf, a well-known Iranian filmmaker. Mohsen supported and mentored Samira in her early career, helping shape her storytelling skills. Together, they created a screenplay that blended real-life events with thoughtful, symbolic storytelling. While Samira brought a fresh and youthful perspective, Mohsen provided experience and guidance, making The Apple a powerful debut that explores complex issues with simplicity and depth.

The Apple received widespread international acclaim, earning several prestigious awards. At the 1999 Independent Cinema Festival in Argentina, it won the Audience’s Prize, the Critic’s Prize, and the Jury’s Special Prize. The film also received the Jury’s Special Prize at both the 1998 São Paulo Film Festival in Brazil and the Thessaloniki Film Festival in Greece. At the 1998 Locarno Film Festival in Switzerland, it was honored with the International Critics Prize, and in the same year, it received the Sutherland Trophy at the London Film Festival in the UK.

The film was screened in the Un Certain Regard section at the 1998 Cannes Film Festival, a category known for showcasing innovative and daring works by emerging filmmakers.

Photos courtesy Google. Excerpts taken from Google.