The Mirror is a 1997 is a remarkable Iranian film directed by Jafar Panahi, centered around Mina (Mina Mohammad Khani), a first-grade schoolgirl in Tehran.

The Mirror begins much like many other Iranian films about children. As school ends, a young girl about seven years old is shown waiting for her mother to pick her up. When her mother doesn’t arrive, the story seems simple: the girl’s journey home on her own.

The opening scene captures the everyday chaos of Tehran. Teachers are shown guiding their young students across a busy street. The children, clearly warned to fear traffic, run across nervously. From the opposite side of the road, the camera captures a flood of honking cars, screeching brakes, and noisy engines—a loud, chaotic world that dwarfs the small figures of the children.

Mina, a first-grade schoolgirl, stands alone outside her school. When it becomes clear that her mother isn’t coming, she bravely decides to make her way home by herself. With the help of strangers one who helps her cross the road, another who gives her a ride on a scooter to a bus stop she makes her way to a bus terminus. But she soon discovers it’s the wrong one. As she continues to navigate the city, Mina becomes increasingly lost and anxious, her confusion and fear growing with each step.

While Mina rides the bus, her path briefly crosses with three women: an elderly woman speaking of past patriarchal control, a young woman silently navigating present gender restrictions, and a girl having her future read, told she will be “no less than a son.” These moments reflect the past, present, and future of Iranian womanhood—all seen through the innocent, searching eyes of a child finding her own way home.

An elderly woman recalls a life of quiet resignation, while a young girl on the bus boldly exchanges glances with a man, defying gender norms. Middle-aged women discuss divorce, reflecting societal judgment. Later, Mina—no longer acting—silently listens in a cab as women debate gender roles, firmly demanding equality. When she refuses to act and chooses to find her way home alone, she symbolizes a new generation: independent, assertive, and unwilling to be confined. The film becomes a powerful portrait of Iranian women’s evolving identity and resilience.

The Mirror not only reflects Iranian society but also turns inward, examining how stories and identities are shaped and reshaped. Like a mirror reversing images, the film reinterprets the roles of women, showing a shift from silence to self-expression, from dependence to agency. It captures a moment of change, highlighting the rise of a new, independent generation.

Wearing her uniform and headscarf, with one arm in a cast, Mina moves through a city full of contradictions—meeting people who are kind, indifferent, or dismissive. Her journey quietly mirrors the complexity of urban life and the evolving identity of Iranian girls growing up in it.

The Mirror, just as the viewer has settled into the gentle rhythm of Mina’s journey, the film takes a sudden and surprising turn. The young actress stops, pulls off her costume, looks directly into the camera, and declares she no longer wants to act in the film. In that moment, the illusion of the story is shattered the fourth wall breaks.

The style of the film changes instantly. The once-smooth camera becomes shaky and hand-held. The picture turns grainy, colours shift, and the focus is off. We now see what raw, unpolished filming really looks like. Panahi and his crew appear on screen, trying to persuade Mina to continue, but she refuses. Since she’s still wearing a mic, the crew decides to keep filming as she tries to make her way home for real.

Though the film eventually returns to smoother shots and planned framing, the situation has changed. Mina is no longer acting, and the crew struggles to follow her. At times, she vanishes into crowds or hops into random taxis. The camera often loses her, showing only noisy traffic or empty streets. Even the sound drops when her mic is accidentally turned off. What started as a story about a lost girl becomes a playful yet thought-provoking look at the boundary between fiction and reality.

In the second half of the film, fiction and reality begin to blur. The “real” Mina isn’t a lost first-grader anymore she’s actually a second-grader who more or less knows her way home. Yet the difference between the character and the actress is slight, and we’re never entirely sure what’s real. Panahi seems to be playing with the conventions of child-focused neo-realist cinema, asking us to think about how much of what we see is shaped or constructed.

When Mina looks directly into the camera and someone off-screen shouts, “Mina, don’t look into the camera!”, the illusion of realism breaks. She then declares she no longer wants to act and just wants to go home. From that moment, the film blurs fiction and reality, following Mina not as a character, but as herself.

By the end, Mina quietly returns the hidden microphone and walks away, leaving the audience questioning what was real, what was staged, and where the boundary between the two truly lies.

Even if the scenes are crafted, the cityscape of Tehran still feels vivid and authentic. We witness everyday moments that reflect deeper social realities: a young couple on a bus can only exchange glances from separate gendered sections; an elderly woman complains of being ignored by her family; other women talk about their troubled marriages. Meanwhile, the men seem absorbed by a radio broadcast of a football match between Iran and South Korea. There are no clear heroes or villains—just ordinary people navigating life in a complex, often challenging urban world.

Panahi’s film may blur fiction and fact, but it captures something very real about Tehran and its people.

The turning point in The Mirror comes when Mina refuses to play Bahareh, rejecting the role of a passive, helpless girl “made to wear a scarf” and “cry all the time.” In doing so, she takes control of her identity and the film itself. From that moment, Panahi steps back, and Mina becomes the director of her own journey—a powerful metaphor for emerging female agency in Iran.

This shift transforms the film from scripted realism to cinéma vérité, blurring fiction and reality. The Mirror lives up to its name—not only reflecting life but reversing it. Mina becomes the opposite of the old woman: no longer silent or resigned, but strong and self-directed. Her journey rewrites the image of Iranian womanhood, showing not just what is, but what can be.

Panahi’s The Mirror is more than a child’s journey home—it’s a clever reflection on cinema, truth, and control. Through Mina’s eyes, the film questions the limits of storytelling and challenges the filmmaker’s authority.

Mina begins as a vulnerable girl navigating chaotic Tehran. But when she breaks the fourth wall and quits acting, she shifts from character to person, reclaiming her autonomy. The film becomes a meditation on performance and reality, asking whether any cinematic truth is ever truly free from artifice.

The Mirror becomes especially compelling at the point where Mina refuses to continue acting and removes her cast. This moment marks a key shift: the filmmaking process itself becomes part of the film. The camera is no longer a passive observer it enters the action, making us intensely aware of its presence. In doing so, the film opens up a space that is both conceptual and real. This is a hallmark of Panahi’s cinema: a thoughtful engagement with the boundaries between fiction and reality, actor and character, sound and image. The tension and gaps between these elements aren’t hidden they’re brought to the surface and grounded in a specific time and place.

In the second half of The Mirror, there’s an exhilarating seven minute stretch where the gap between image and sound becomes strikingly clear. The camera loses sight of Mina, yet still hear her footsteps. Meanwhile, the images on screen unfold in silence, without any corresponding sound. This disjunction draws attention to the constructed nature of cinema reminding us that what we see and hear are often separate, stitched together by technology and illusion. It’s a powerful moment where form itself speaks, revealing the artifice behind the image.

Panahi seems gentle, he represents the same patriarchal system he’s critiquing, continuing the film simply because he started it. As the narrative breaks down into fragments, Mina’s refusal to be seen often hidden or walking away grows more powerful. Tearing off her mic and closing the door on the camera, she rejects both role and representation. Her rebellion may not be fully conscious, but it is deeply sincere.

Cinematography by Farzad Jadat and editing by Jafar Panahi, The Mirror blends simplicity with sophistication. It begins as a quiet, observational drama and transforms into a self-reflexive commentary on the illusion of realism in cinema. Through this layered structure, Panahi challenges viewers to reconsider what they believe is “real” on screen.

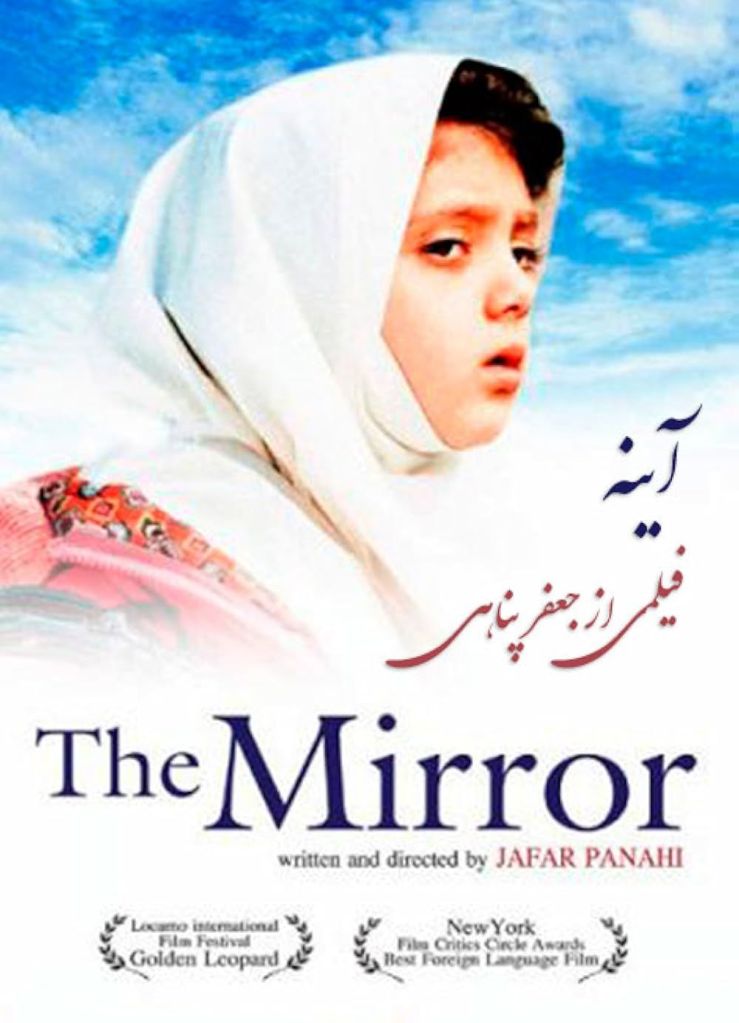

The Mirror received significant international acclaim for its innovative storytelling and bold cinematic experimentation. It won the Golden Leopard at the Locarno International Film Festival, one of Europe’s most prestigious honors. At the Istanbul International Film Festival, Jafar Panahi was awarded the Golden Tulip, recognizing his exceptional direction. The film also earned Panahi the Silver Screen Award for Best Asian Director at the Singapore International Film Festival, further cementing his status as a leading voice in world cinema. Additionally, The Mirror was nominated for the Golden Spike at the Valladolid International Film Festival in Spain, underscoring its global resonance and artistic significance.

Photos courtesy Google. Excerpts taken from Google.