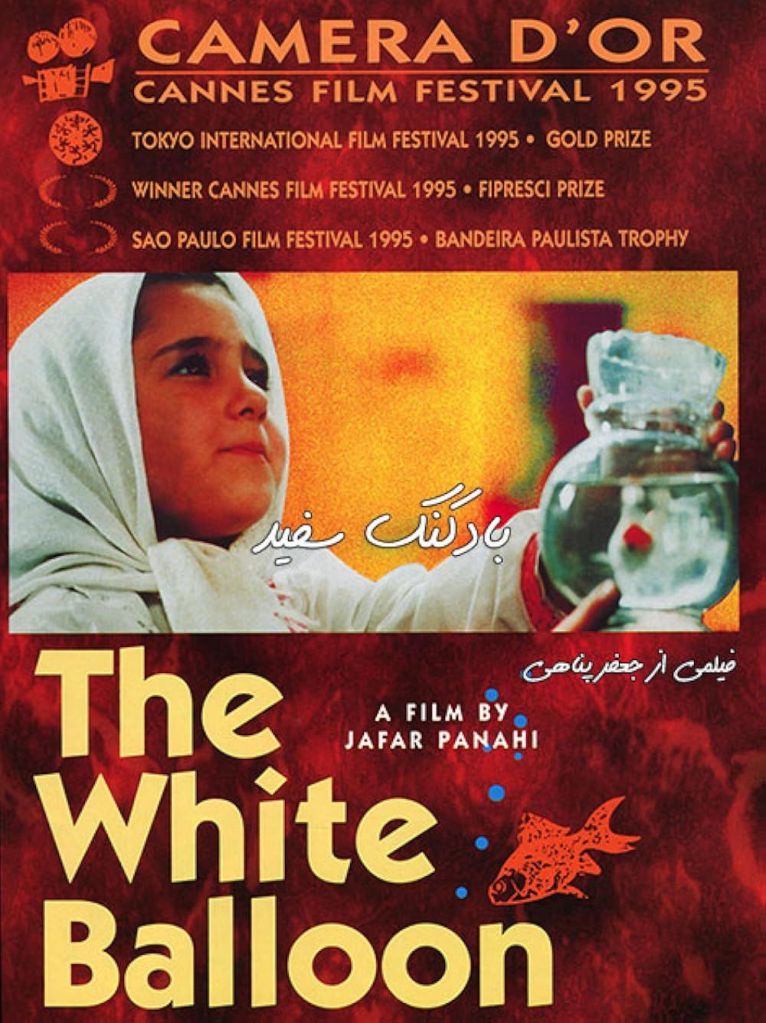

The White Balloon is a 1995 Iranian film that marked the feature-film directorial debut of Jafar Panahi, with a screenplay written by the acclaimed filmmaker Abbas Kiarostami. A gentle, humanistic story told through the eyes of a young girl, the film exemplifies the quiet, observational style that would become a hallmark of Iranian New Wave cinema.

The White Balloon, set on the eve of Nowruz, gains emotional and cultural depth from its festive context. Nowruz, Iran’s New Year celebrated on the first day of spring, is a time of renewal, family gatherings, and symbolic rituals, much like Christmas in the West. Central to the tradition is the haft sin table, which includes a goldfish as a symbol of life and vitality. Razieh’s desire for a vibrant goldfish reflects not mere whimsy but a child’s deep wish to participate meaningfully in her family’s celebration.

In The White Balloon, the use of real-time storytelling plays a crucial role in creating intimacy and urgency. Early in the film, a radio broadcast informs us that the Iranian New Year (Nowruz) will begin in 78 minutes. From this point on, the film unfolds with remarkable fidelity to diegetic time—the duration of the story in the film closely matches the actual screen time. This choice anchors the narrative in the present moment, allowing viewers to experience Razieh’s journey as it happens, almost minute by minute.

The presence of Haji Firuz clowns in the opening shot, dancing and singing in the streets, not only situates the story in a festive cultural setting, but also enhances the sense of public celebration and approaching transition. As Razieh embarks on her emotionally charged mission to buy a goldfish, the ticking clock adds subtle pressure, mirroring the countdown to the New Year and giving her seemingly small quest a heightened emotional weight.

Razieh, a determined seven-year-old girl, persistently nags her mother for a plump, colorful goldfish she spotted in the bazaar. Her longing is tied not just to aesthetic preference, but to the symbolic importance of the goldfish in the Nowruz haft sin display—a symbol of life and renewal. Her insistence reveals her deep emotional investment in participating fully in the holiday tradition.

This sequence also introduces the family dynamic. The mother, played with natural grace by Fereshteh Sadre Orafaiy, is preoccupied with Nowruz preparations and dismisses the idea of spending money on a new goldfish when their home already has a pond full of fish. Her practicality contrasts with Razieh’s emotional idealism. RaziAes older brother, and hear the gruff voice of the father, who is never seen—a directorial choice that subtly critiques patriarchal authority by keeping it offscreen yet still influential.

The setting—a modest home in a compound near a busy Tehran market—grounds the story in a realistic urban working-class environment. The sequence’s emotional arc is simple but resonant: Razieh argues, pleads, and finally wins. Her mother reluctantly hands over a 500-toman note, instructing her to spend only 100 tomans on the goldfish and return the change.

This moment marks a turning point: Razieh has achieved her first goal—permission and money—and the story now shifts toward the next phase of her adventure: venturing into the city alone to buy the goldfish. What follows will no longer be about persuasion, but about navigating obstacles, trust, and the kindness or indifference of strangers. The everyday act of shopping becomes a child’s emotional journey, richly layered with cultural meaning and quiet tension.

“The Snake Charmers”, Razieh’s journey takes a brief, emotional detour as she’s drawn to a street performance, despite her mother’s warning. Her curiosity leads to a tense moment when the snake charmers snatch her 500-toman note during their act, threatening her mission. The scene blends humor and danger, reflecting the unpredictable and often indifferent nature of the outside world through a child’s eyes. Though shaken, Razieh recovers her money and continues on, a bit more aware of how fragile her independence is. The episode’s goal—emerging intact—is achieved, but with raised emotional stakes.

In this important part of The White Balloon, Razieh finally finds the goldfish she wants, but then realizes she has lost the 500-toman note. She becomes upset again, but a kind older woman helps her retrace her steps. They manage to find the money, but it has fallen through a metal grate in front of a closed shop.

The woman asks a nearby tailor, Mr. Bachtiari, for help. He agrees but gets too busy with problems in his shop and doesn’t help Razieh. Now, even though the money is found, Razieh can’t reach it, and she doesn’t know what to do.

This scene shows how difficult the world can be for a child. People may want to help, but they are often too distracted or busy. The goal of the scene finding the money is done, but getting it back is still a problem. Razieh is so close to success, but still stuck, waiting for help.

Razieh’s older brother, Ali, finally finds her on the street. More confident and assertive than Razieh, Ali steps in and tries to convince Mr. Bachtiari to help retrieve the money from the drain. However, he too makes little progress. Mr. Bachtiari, still caught up in his own business, suggests they wait until after the Nowruz holiday, when the owner of the closed shop might return and open the grate.

While this suggestion may seem reasonable to an adult, it feels like a disaster to the children, who know they can’t go home without the money. Their parents, especially their father, are demanding, and the consequences of failure seem serious to them. With the urgency of the New Year countdown ticking away, Ali sets off to try another solution: he goes in search of the shopkeeper’s address, hoping to find someone who can unlock the grate before it’s too late.

Razieh is approached by a young army soldier from the provinces. Alone and waiting near the drain, she is clearly uncomfortable as the soldier begins to chat with her. Like many children, she has been taught not to talk to strangers, and the soldier’s intentions are left deliberately vague—he could be just lonely, curious, or even looking for an opportunity to take the money.

This scene is filled with quiet suspense. The soldier tries to gain Razieh’s trust, but she remains hesitant and fearful. Just as the situation grows more uncomfortable, Ali returns and quickly ends the conversation. The soldier leaves, and Razieh is safe once more.

Final and emotionally resonant episode of The White Balloon, Razieh and Ali spot an Afghan boy selling balloons nearby. After a brief tussle over his balloon stick, the children and the boy decide to collaborate. They hatch a simple yet clever plan: use the stick with chewing gum on the end to retrieve the 500-toman note from beneath the grate.

Ali briefly considers stealing gum from a blind street vendor, highlighting his desperation, but ultimately chooses not to. Meanwhile, the Afghan boy returns having honestly bought gum and the plan is put into action. The children successfully recover the money, marking the resolution of their long, frustrating journey.

Razieh and Ali then joyfully rush off to buy the goldfish, their mission finally fulfilled. But the film’s final, poignant image lingers not on them, but on the Afghan boy, left behind with his one remaining white balloon. Alone, quiet, and unacknowledged, his solitary figure offers a gentle but powerful reflection on class, belonging, and invisibility.

This closing shot deepens the film’s message, reminding viewers that even in moments of joy, not everyone is included in the celebration.

The charm of The White Balloon lies in its ability to elevate a child’s seemingly small world into a space of genuine drama and emotional depth. Jafar Panahi presents the story entirely from a child’s perspective, both literally and emotionally. The camera stays at Razieh’s eye level, seeing only what she sees, immersing the viewer in her anxieties, setbacks, and joys.

Aida Mohammadkhani’s portrayal of Razieh is natural, tender, and utterly convincing. Her tearful panic in the snake charmer scene and her bursts of joy upon rediscovering her money or spotting her beloved goldfish feel unfiltered and authentic likely the result of Panahi’s careful direction and his ability to draw out sincere performances from nonprofessional actors.

The supporting cast also adds to the film’s realistic feel. No one seems like they’re acting everyone, from the busy tailor to the balloon seller, feels like a real person. Panahi’s careful direction and camera work make an ordinary street in Tehran feel alive, full of both hope and danger.

Although Panahi’s style is different from the Italian neorealists, he shares their goal of showing real everyday life with honesty. Like directors De Sica or Rossellini, he doesn’t rely on big drama or spectacle. Instead, he shows the deep emotions hidden in ordinary moments. In this way, The White Balloon is more than just a sweet children’s story it’s a powerful look at childhood, where small actions feel big, and the world can be both magical and scary.

The film was praised around the world and won many important awards. Most notably, it won the Caméra d’Or at the 1995 Cannes Film Festival, given to the best first feature film. The White Balloon was also named one of the 50 best family films ever by The Guardian and was included in the British Film Institute’s list of “50 Films You Should See by the Age of 14.” These honors show the film’s wide appeal and artistic value.

The White Balloon was chosen as Iran’s official entry for Best Foreign Language Film at the 68th Academy Awards, it faced controversy. The Iranian government tried to pull the film from the Oscars, but the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences refused and kept it in the competition. In the end, the film was not nominated.

The White Balloon is still seen as a quiet masterpiece and an important start to Jafar Panahi’s career. It shows the influence of Kiarostami’s style, focusing on simple stories, real-life settings, and the emotions of children to explore bigger issues in society.

Photos courtesy Google. Excerpts taken from Google.