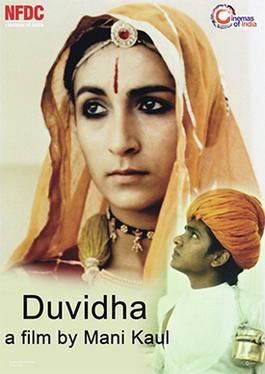

Duvidha (1973) is a seminal Hindi film directed by Mani Kaul, adapted from a short story by Rajasthani author Vijaydan Detha. It marks Kaul’s third feature and his first film in colour, and is widely regarded as one of his most accomplished works.

Set in rural Rajasthan, the film tells the tale of a merchant’s son (Ravi Menon) who returns home with his new bride (Raisa Padamsee), only to be sent away again on family business. On their wedding day, a ghost residing in a banyan tree becomes enchanted by the bride’s beauty and is overcome with desire for her. During the oxcart journey to the groom’s family home, the groom informs his young wife that he must soon leave for a distant town to seek his fortune a journey that will take five years. He further declares that there is no point in consummating the marriage before his return.

After his departure, the ghost sees an opportunity. He assumes the groom’s appearance, returns to the family home, and offers a convincing excuse to the groom’s father for his sudden reappearance. The bride, unaware of the ghost’s true identity, accepts him as her husband.

In his absence, a ghost, captivated by the young bride’s arrival, falls in love with her. Assuming her husband’s form, the ghost lives with her, and she eventually bears his child. The dilemma intensifies when the real husband returns, leading to a quiet yet unsettling confrontation of reality, identity, and desire. A local shepherd ultimately traps the ghost in a bag, bringing the folktale to its folkloric conclusion.

When the groom informs his bride of his plan to leave for five years, she doesn’t protest but is visibly stunned. As he departs, he urges her to “uphold the honor of the house” and resist temptation. When the ghost appears in the groom’s form, he could easily deceive her but instead, in a gesture of love and integrity, he confesses the truth. In a surprising act of agency, the bride accepts him as her husband and consummates the relationship, setting off major dramatic consequences. Duvidha (meaning Dilemma) becomes a powerful story of the bride’s silent choice represents a bold, radical defiance of patriarchal norms.

Raisa Padamsee, as Lacchi, conveys the inner turmoil of a young bride through expression alone she never speaks, yet says everything with her face and gestures. Duvidha can be seen differently depending on perspective: a story of betrayal for the husband, or of duty and mistaken identity for the wife. As a folktale, it hints at how women’s desires were once silenced and rewritten as moral warnings. The film emphasizes the wife’s silence—she listens, is lectured, yet acts on her will. Her quiet defiance challenges social norms that shame female desire.

While she stays silent and hidden behind her veil on screen, her voice-over reveals her true feelings. In one moment, she says, “To parents, a daughter is like a weed that must be uprooted,” showing the emotional and social pressure women face. Married at sixteen, Lachhi is left alone in her husband’s home while he goes away, and it is only through her inner voice that hear her sadness, longing, and quiet strength.

Mani Kaul’s Duvidha employs a slow, meditative structure to explore the bride’s inner world through parallel and conflicting timelines. With minimal dialogue, the film relies on voice-over, composed visuals, and silence to convey emotion. Kaul’s aesthetic boldness is evident in his use of close-ups, stylized framing, and symbolic elements like the bride’s layered veils, which act as emotional filters. A key moment, where the groom denies her request to pick fruit, captures the central tension between her natural desire and his rigid concern for social status.

The scene where the bride embraces the ghost captures romantic ecstasy with subtlety and stillness. Kaul’s visual style emphasizes gestures, fabric, and silence over action or dialogue, while bold editing and a layered soundtrack tie the fragmented imagery together.

Duvidha captures the tension between social conformity and inner conscience, culminating in powerful moments when the bride, once veiled and downcast, finally meets the camera’s gaze directly. Kaul’s refined aesthetic his attention to landscape, costume, and ritual transforms into a vehicle for radical subjectivity. His style urges viewers not to mistake silence for consent, a bowed head for submission, or outward tradition for a lack of inner resistance.

The cinematography of Duvidha, by Navroze Contractor, plays a vital role in shaping the film’s painterly, dreamlike quality. Inspired by Kangra and Basohli miniature paintings, Contractor used static shots, natural light, and long takes to mirror the film’s meditative pace. His visuals emphasize mood and psychological depth over action, aligning with Kaul’s experimental approach. Especially through the bride’s inner world, the film becomes a study in visual emotion. Contractor’s elegant, innovative work makes Duvidha a landmark not only in Indian parallel cinema but also in cinematic artistry.

The music, performed by Rajasthani folk musicians Ramzan Hammu, Latif, and Saki Khan, adds authenticity and depth to the film’s haunting atmosphere.

Critically acclaimed for its experimental and poetic approach, Duvidha won Mani Kaul the National Film Award for Best Direction and the Filmfare Critics Award for Best Film in 1974. The film was also screened widely across Europe, where it was celebrated for its originality and visual sophistication.

Duvidha is a film of haunting stillness and lyrical restraint where silence speaks louder than words, and each image captures a world of longing, confinement, and delicate beauty. Rooted in folklore yet floating in a timeless haze, it offers a poetic meditation on love, identity, and the quiet sorrow of a life suspended between desire and duty.

Photos courtesy Google. Excerpts taken from Google.