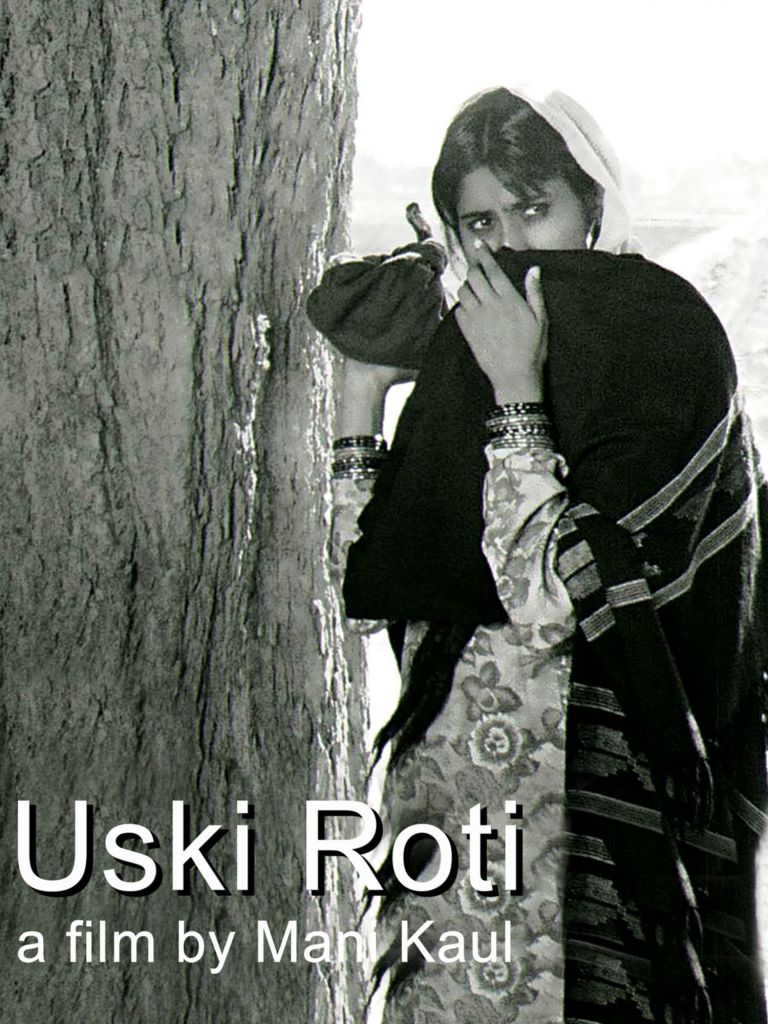

Uski Roti is a 1969 Hindi film directed by Mani Kaul in his feature film debut. Based on a short story by Mohan Rakesh, who also wrote the film’s dialogue, the film is a landmark of the Indian New Wave movement.

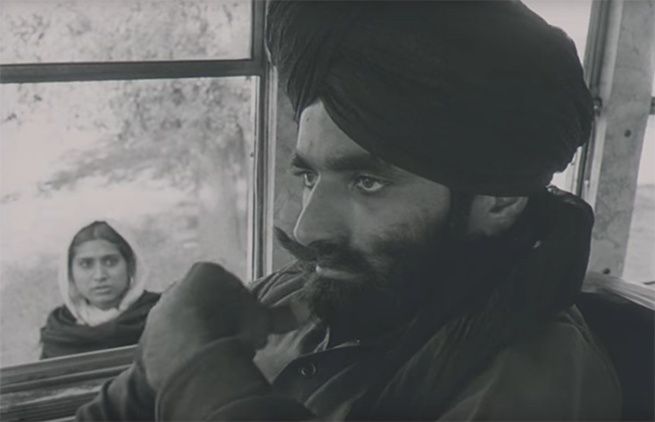

The film follows the life of a bus driver, Sucha Singh (Gurdeep Singh), and his wife, Balo (Garima). Every day, Balo walks miles to fetch bread for her truck driver husband and waits by the roadside, hoping for a brief, wordless moment when his truck passes through their village. Bound by routine and silent devotion, she clings to this ritual even as her marriage begins to crumble. Her husband, distant and distracted, spends his time with friends and a mistress, while she quietly bears the weight of suspicion and sorrow.

As Balo’s concern for her younger sister deepens, so does her emotional burden. One day, when her sister faces the unwanted advances of a man in the village, Balo rushes to help her. This delay causes her to miss the brief, silent moment she shares each day with her husband, Sucha Singh, as he passes by in his truck. Angry at her absence, he drives off without taking the food she brought and declares he will return home only when he chooses.

Uski Roti ends with Balo’s silent, sorrowful gaze a moment of quiet defiance that encapsulates her emotional isolation. The film’s slow pace, ambient sound, and fragmented imagery evoke the stagnant rhythm of rural life. Balo’s tension stems from her emotionally distant husband, Sucha Singh, a bus driver more invested in cards and his mistress than in their marriage. Their bond is depicted through silence, gestures, and absence, with no backstory to soften its bleakness. Stark contrasts between Balo’s luminous countryside and Sucha Singh’s shadowy inn underscore their emotional divide, as his restless motion contrasts her still, enduring presence.

Uski Roti unfolds in silence and stillness, exposing the quiet pain of isolation and the fragility of human relationships shaped by emotional and physical distance. Told through a disjointed, non-linear structure, the film reflects the inner turmoil of its characters, especially Balo and her indifferent husband, Sucha Singh. His emotional absence and her patient routine define a marriage devoid of connection. Balo’s nighttime journey and eventual return only to find her sister assaulted underscore the film’s bleak portrait of female suffering and the cyclical nature of patriarchal neglect. Denying resolution, the film ends as it unfolds: in ambiguity, silence, and resignation.

The film was shot on location in a village in Punjab. Uski Roti marked a radical departure from the conventions of narrative cinema, dispensing with traditional plot structure and forgoing established film actors. Dialogue is sparse and delivered in undramatic monotones, evoking the style of Robert Bresson, a major influence on director Mani Kaul. The film unfolds through silence, mood, and imagery rather than action or dialogue.

Cinematographer K. K. Mahajan uses the camera to linger on faces, hands, and textured exteriors—mud walls, a windswept highway, a guava orchard—crafting a visual language of stillness and fragmentation. The emphasis on hands is especially Bressonian, echoing a tactile intimacy central to the film’s aesthetic. As critic Derek Malcolm observed, “The film is not an orthodox narrative, dealing instead with silence, mood and imagery.”

Kaul sought to explore what was inherently cinematic in adapting a written script, minimizing gestures to match the film’s rigorously structured form. He employed two distinct lenses to reflect Balo’s physical and mental worlds: a 28mm wide-angle for deep-focus spatial depth, and a 135mm telephoto that reduced focus to a narrow slice of the frame. As the film progresses, this visual schema is gradually reversed, marking Uski Roti as one of Indian cinema’s most meticulously composed works. The film’s spatial design recalls the large canvases of Amrita Sher-Gil, while its soundtrack isolates everyday sounds to parallel the fragmented imagery.

In a 1994 interview, Kaul reflected on his intent: “When I made A Day’s Bread, I wanted to completely destroy any semblance of a realistic development, so that I could construct the film almost in the manner of a painter.”

Cinematographer K. K. Mahajan was awarded the National Film Award for Best Cinematography, while Mani Kaul received the 1970 Filmfare Critics Award for Best Movie, recognizing Uski Roti as a landmark in Indian parallel cinema.

Photos courtesy Google. Excerpts taken from Google.