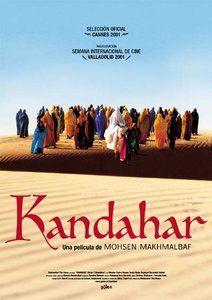

Kandahar (“Qandahar”) is a 2001 Iranian film directed by Mohsen Makhmalbaf. The story takes place in Afghanistan during the time of the Taliban rule. The original Afghan title of the film is Safar-e Ghandehar, which means “Journey to Kandahar”. It is also known by another name: The Sun Behind the Moon.

The film Kandahar is about a woman named Nafas, who is originally from Afghanistan but now lives safely in Canada. One day, she gets a sad letter from her sister, who is still in Afghanistan. The letter says that the sister is planning to kill herself during the next solar eclipse because of the pain and unfair treatment women face under the Taliban.

Nafas decides to go back to Afghanistan to try to stop her sister. She goes to Iran, wears a burqa to hide her identity, and joins a group of Afghan refugees pretending to be a wife in the group. On the way to Kandahar, they are attacked by robbers. The others turn back, but Nafas keeps going alone, risking her life to reach her sister before it’s too late.

Nafas hires a young boy named Khak, who was recently kicked out of a religious school, to help guide her. During the journey, Nafas drinks dirty water and becomes sick. Khak takes her to a village doctor for help.

The doctor turns out to be an African-American man who became a Muslim. He wears a fake beard, which he jokes is like “a man’s burqa,” because he can’t grow a real one. Worried he might get caught by the Taliban, the doctor sends Khak away and continues the journey with Nafas in a horse cart.

While traveling, he tells Nafas that he isn’t a real doctor, he never had any medical training. He also says he feels sad about how things have changed in Afghanistan under Taliban rule.

As Nafas travels through Afghanistan, she speaks into a small tape recorder to share her thoughts and experiences. She notices that while the country has developed weapons, other parts of life especially for women have been left behind.

She sees how badly war has damaged Afghan society. Children steal from dead bodies just to survive. People fight over artificial legs and arms in case they step on landmines. Even doctors aren’t allowed to properly treat women they can only examine them from behind a curtain with a small hole. Through all this, Nafas learns more about the deep suffering and unfair treatment Afghan women face every day.

When the doctor refuses to go further out of fear, Nafas continues her journey alone. She follows a man disguised in a burqa who had tricked the Red Cross into giving him artificial legs. Together, they join a wedding group heading toward Kandahar.

However, the wedding party is stopped by the Taliban for singing and playing music acts banned under their rule. The man Nafas was following is caught and taken away after being unmasked. Nafas, still in disguise, is allowed to continue with the others.

In the final scene, as the sun sets, Nafas is close to reaching Kandahar but she remains trapped by the burqa, a symbol of the oppression and silence forced upon women under Taliban rule.

In the film Kandahar, Mohsen Makhmalbaf played multiple key roles. As director, he guided the overall artistic vision, style, and storytelling of the film. Writer, he developed the screenplay, crafting the narrative based on a partly true story. Producer, he oversaw the production, managing resources, funding, and bringing the project to completion. His involvement in all three major creative roles shows how deeply personal and controlled this project was for him.

In the film, Nelofer Pazira plays Nafas, an Afghan-Canadian journalist who undertakes a dangerous journey back into Taliban-controlled Afghanistan in a desperate attempt to save her sister, who has threatened to take her own life. The role is semi-autobiographical, closely mirroring Pazira’s real-life experience of trying to return to Afghanistan in 1996 to locate a childhood friend. Director Mohsen Makhmalbaf shaped the narrative around her personal story, with Pazira essentially portraying a fictionalized version of herself. Her performance carries a quiet authenticity, blending personal memory with cinematic expression, and anchoring the film’s emotional and political weight.

Cinematographer Ebrahim Ghafouri captures the desert landscape of Kandahar as both starkly beautiful and forbidding, emphasizing the isolation of Nafas’s perilous journey. Riding in a truck with other women, her identity erased by the burqa, Nafas faces roadblocks and danger until she is guided by a young boy, Khak, whose survival instincts reflect the harsh realities of life under Taliban rule. Ghafouri’s documentary-style realism powerfully conveys both the physical and emotional devastation. Filmed mostly in Iran, with some scenes shot secretly in Afghanistan, the film blurs fiction and reality especially with real people, including Nelofer Pazira, playing versions of themselves.

As the editor, Makhmalbaf shaped the final version of the film choosing which scenes to include, how to arrange them, and how to control the pace and rhythm of the story. This editing helped keep the film focused and emotionally powerful.

Mohammad Reza Darvishi composed the film’s background music, adding emotional depth and atmosphere. His music supports the mood of different scenes, from quiet sorrow to tense moments, enhancing the viewer’s experience.

The film Kandahar premiered at the 2001 Cannes Film Festival and went on to receive significant critical acclaim. Director Mohsen Makhmalbaf was awarded the prestigious Federico Fellini Prize by UNESCO that same year. The film also won the Freedom of Expression Award from the National Board of Review in the USA (2001), and the Prize of the Ecumenical Jury at Cannes. At the Thessaloniki Film Festival in 2001, Kandahar received the FIPRESCI Prize, recognizing Makhmalbaf “for a visionary, poetic, yet unsparing revelation of human suffering in conflict-torn Afghanistan.” Additionally, in 2002, the film received the Audience Award for Best Female Voice at the Voci nell’ombra festival in Italy, honoring Sabrina Duranti for her dubbing of Nelofer Pazira in the Italian version.

Photos courtesy Google. Excerpts taken from Google.