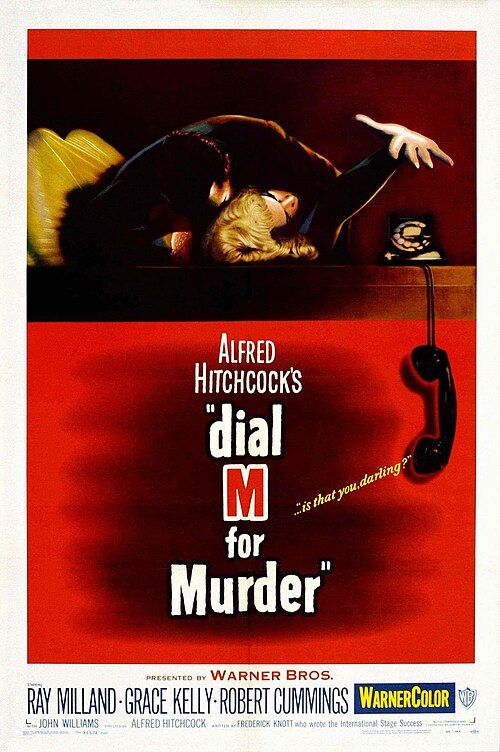

Dial M for Murder is a 1954 American crime thriller movie directed by Alfred Hitchcock. It stars Ray Milland, Grace Kelly, Robert Cummings, Anthony Dawson, and John Williams. The story comes from a play written by English writer Frederick Knott. The play first appeared on BBC Television in 1952, and then it was shown on stage in London and New York the same year.

The film begins quietly with Tony Wendice (Ray Milland) and his wife Margot (Grace Kelly) having breakfast in their ground-floor apartment. While reading the newspaper, Margot notices a news item saying that the ship Queen Mary has arrived in London, bringing with it writer Mark Halliday. This catches her attention.

Margot says nothing about the troubling news, but that evening, Mark Halliday arrives at the flat. From their greeting and easy familiarity, it’s evident they were once romantically involved, having had an affair the previous year. Margot confides in Mark that Tony has changed. She believes her husband is unaware of their past relationship and even adds that Tony gave up his tennis career for her—a claim Mark finds hard to believe, though he doesn’t challenge it.

But there’s a more immediate concern. Although Margot had burned all of Mark’s old letters after reading them, she mistakenly kept one. That lone letter was stolen, and now she’s being blackmailed. She already sent money in exchange for its return, but the letter never came back.

Their conversation is interrupted by the sound of the front door—Tony has returned home. He announces that their plans for the evening have changed: he won’t be able to join them for the theatre and dinner after all, as he needs to finish some tedious monthly reports. Still, he encourages Margot and Mark to go without him and suggests that if she calls during the intermission and he’s finished, he might still be able to join them.

Before they leave, Tony casually invites Mark to a stag party the next evening. Mark feels socially obligated to accept.

But once Margot and Mark are gone, Tony doesn’t touch any reports. Instead, he draws the curtains and makes a mysterious phone call. Posing as a man named Fisher, he contacts someone called Captain Lesley under the pretext of buying a second-hand car. Claiming a knee injury, Tony urges Lesley to come to the flat that evening to finalize the deal quickly.

When the doorbell rings, Tony grabs a cane to keep up the pretense of injury and answers the door. The visitor isn’t a car dealer but C.A. Swann, an old college acquaintance, played by Anthony Dawson. Swann, clearly down on his luck, is puzzled and wary—he never advertised a car for sale. Tony, unfazed, explains that his marriage to Margot has long been troubled. He had married her for her money, but his constant travel as a tennis pro caused them to grow apart.

Tony confesses that, while supposedly en route to a tennis championship, he secretly followed Margot and saw her meet another man in Chelsea. Though not driven by love, he was shaken—mainly by the threat to his comfortable life funded by her wealth. That day, he sat in a pub thinking of ways to kill her lover, even briefly considering murdering Margot herself.

Swann, intrigued but wary, listens as Tony reveals that he was the one who stole Margot’s letter and orchestrated the blackmail. He drops the letter in front of Swann, subtly tempting him, though Swann remains unsure where this is all headed.

Tony reveals he never wanted to buy a car—he sought Swann out because he had a plan. Swann grows uneasy, but he’s stunned when Tony proposes that he murder Margot. Swann tries to refuse and threatens to expose him, but Tony has him cornered: Swann’s fingerprints are on the stolen letter, and his criminal past makes him vulnerable. With no escape, Swann reluctantly agrees.

Tony outlines his plan: the next night, while he’s out with Mark, Margot will be home alone. He’ll hide her key under the stair carpet, and Swann is to sneak in, hide behind the curtains, and kill her when Tony calls at exactly 11 p.m. Swann must then stage it as a burglary and leave through the French doors.

Tony sees it as foolproof, with Mark providing his alibi. But trouble arises—Margot doesn’t want to stay home alone. Tony manipulates her emotionally until she agrees. After he and Mark leave, Tony discreetly places the stolen key under the carpet for Swann.

Swann enters the flat using the hidden key and hides behind the curtains as planned. But things go wrong—Tony’s watch stops, and the club phone is busy, delaying his call. Just as Swann is about to leave, the phone finally rings. Margot, half-asleep, answers it, and Swann moves in to attack.

Swann attacks her with his scarf. But she fights back and fatally stabs him with a pair of scissors. Instead of the planned whistle, Tony hears her crying for help. Quickly taking control, he tells her not to speak to anyone and rushes home.

Tony leaves Mark at the club and rushes home in a taxi. There, he comforts a visibly shaken Margot and, while pretending to examine Swann’s body, discreetly takes what he believes is her key from Swann’s coat pocket and slips it into her handbag. He persuades her to take an aspirin and go to bed, assuring her that he’ll explain everything to the police.

Once she’s out of the way, Tony meticulously stages the crime scene. He burns Swann’s scarf, places one of Margot’s stockings outside the French doors to suggest a break-in, and slips Mark’s stolen letter into Swann’s breast pocket to strengthen the blackmail motive. With everything arranged, he calmly waits for the authorities—his original plan failed, but his cover-up is now in motion.

The next day, Tony persuades Margot not to mention that he told her not to call the police. When Chief Inspector Hubbard arrives to question them, Margot—still confused and emotionally shaken—gives conflicting answers that raise further doubts. Tony subtly manipulates the conversation, pretending to support Margot while guiding Hubbard toward his own version of events.

When Hubbard suggests Swann may have entered through the front door, Tony lies, claiming Swann must have stolen Margot’s handbag earlier and copied her key. As Tony anticipated, the inspector doesn’t believe the story and instead concludes that Margot killed Swann to stop the blackmail. The evidence—Mark’s letter and inconsistencies in Margot’s account—seems to support that theory. Margot is arrested, tried, and ultimately sentenced to death for Swann’s murder.

Months later, just before Margot’s execution, Mark visits Tony with a desperate plan to save her. He urges Tony to confess to the police—by fabricating a story that he hired Swann to kill Margot. Ironically, it’s close to the truth. Mark argues that while Tony might go to prison, Margot’s life would be spared.

Suddenly, Chief Inspector Hubbard arrives, and Mark quickly hides in the bedroom. Hubbard questions Tony about his recent spending, cleverly tricks him into admitting his latchkey is in his raincoat, and brings up the missing attaché case. Tony claims he lost it—but Mark finds it on the bed, full of cash. Realizing this was the money meant for Swann, Mark confronts Tony. Cornered, Tony shifts the story again, claiming it was Margot’s blackmail payment and he had hidden it to protect her. Hubbard pretends to accept the explanation, while Mark storms out in frustration.

Before Tony leaves, Hubbard secretly switches their raincoats. Once Tony is gone, Hubbard returns to the flat using Tony’s key—now in his possession—with Mark close behind. Earlier, Hubbard had discovered that the key in Margot’s handbag actually belonged to Swann, and deduced that Swann had returned the real key to its hiding spot after entering. Now certain that Tony orchestrated the murder, Hubbard sets a trap.

He has Margot brought from prison by plainclothes officers. When she tries to open the front door with the key in her handbag, it doesn’t work. She’s forced to enter through the garden, proving she had no idea about the hidden key—clear evidence that she’s innocent.

Hubbard has Margot’s handbag quietly returned to the police station. Later, when Tony arrives and realizes he doesn’t have his key, he instinctively grabs Margot’s bag and tries her key—but it doesn’t work. He then retrieves the hidden key from under the stair carpet and unlocks the door.

That single action seals his fate—it proves he knew where the key was hidden, confirming Hubbard’s suspicions and clearing Margot of guilt. As the police block his escape, Tony remains composed, pours himself a drink, and coolly congratulates Hubbard on solving the case.

As director, Alfred Hitchcock plays a pivotal role in transforming Dial M for Murder from a stage-bound thriller into a visually compelling and suspenseful film. Despite the confined setting and dialogue-heavy script, Hitchcock infuses the film with cinematic tension through clever camera angles, careful blocking, and a masterful control of pacing. He turns the apartment into a pressure-cooker environment, using lighting, shadows, and visual cues—like the lingering focus on the scissors—to heighten suspense and engage the viewer’s imagination. His precise direction ensures that every gesture, pause, and glance contributes to the growing unease, proving that a limited space in the hands of a master can still deliver edge-of-the-seat storytelling.

Ray Milland as Tony Wendice delivers a suave yet chilling performance as the calculating husband plotting his wife’s murder. He plays Tony with cool precision, masking sinister intentions under a charming and composed exterior. His control over tone and body language makes his manipulation of both people and situations believable. Milland makes Tony’s intelligence and ruthlessness compelling, portraying a man whose charm masks deep moral rot.

Grace Kelly as Margot Wendice brings vulnerability and grace to the role of Margot, the unsuspecting wife caught in her husband’s deadly plan. She moves effortlessly from warmth to panic, especially in the scene where she fights off her attacker. Kelly portrays Margot’s confusion, fear, and later resignation with subtlety, especially in courtroom and prison sequences. Her emotional range adds depth to a character who could have easily been passive.

Robert Cummings as Mark Halliday plays Mark Halliday, the crime novelist and Margot’s former lover, with earnestness and intelligence. While less dynamic than Milland or Kelly, Cummings brings a sense of moral clarity and urgency, especially in the later parts of the film as he begins to suspect Tony. His character is key in shifting the narrative from tragedy toward justice, and he handles the role of the outsider-detective well.

John Williams as Chief Inspector Hubbard gives a standout performance as the quietly observant Chief Inspector. With dry wit and measured delivery, he plays Hubbard as a methodical thinker, subtly letting the audience in on his suspicions before the characters catch on. Williams’s calm presence contrasts sharply with the tension in the film, and his role in the final twist is delivered with understated brilliance.

Each actor contributes significantly to the tension and psychological depth of the film, creating a tightly woven web of deception, suspicion, and suspense.

Robert Burks, the cinematographer for Dial M for Murder and a longtime collaborator of Alfred Hitchcock, played a crucial role in transforming the film’s stage-play origins into a visually engaging cinematic experience. Working within the confined space of Tony and Margot’s flat, Burks used creative lighting, camera angles, and movement to build tension and maintain visual interest. Originally shot for 3D, he composed scenes with depth and layering in mind, placing objects at various distances to enhance perspective—even though most audiences saw it in 2D. His thoughtful use of color further heightened the mood, with warm tones in calmer scenes and stark shadows during moments of suspense, perfectly complementing Hitchcock’s psychological thriller.

Originally shot in dual-strip polarized 3D, the film was released primarily in 2D due to waning public interest and the technical challenges of 3D projection. It grossed an estimated $2.7 million at the North American box office in 1954.

Photos courtesy Google. Excerpts taken from Google.