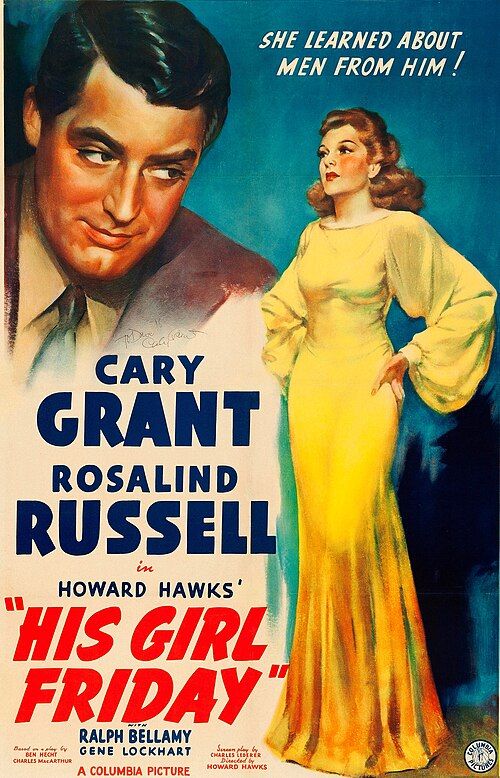

His Girl Friday is a 1940 American comedy film directed by Howard Hawks and produced by Columbia Pictures. It stars Cary Grant and Rosalind Russell in the lead roles, with Ralph Bellamy and Gene Lockhart in supporting roles. The story follows Walter Burns, a clever, quick-witted, fast-talking newspaper editor. Walter’s best reporter and ex-wife, Hildy Johnson, is now engaged to marry another man. To win her back, Walter persuades her to cover one last story—the trial of accused murderer Earl Williams.

Film remains one of the most dazzling screwball comedies ever made, a film where the speed of the dialogue and the sharpness of the performances outpace even the most frantic newsroom deadlines. Based on Ben Hecht and Charles MacArthur’s 1928 play The Front Page, the film keeps the basic setting—a pressroom buzzing with reporters covering a sensational murder case—but adds a crucial twist: Hildy Johnson, the star reporter, is now a woman. This single change injects both gender conflict and romantic tension into a story already bristling with journalistic energy.

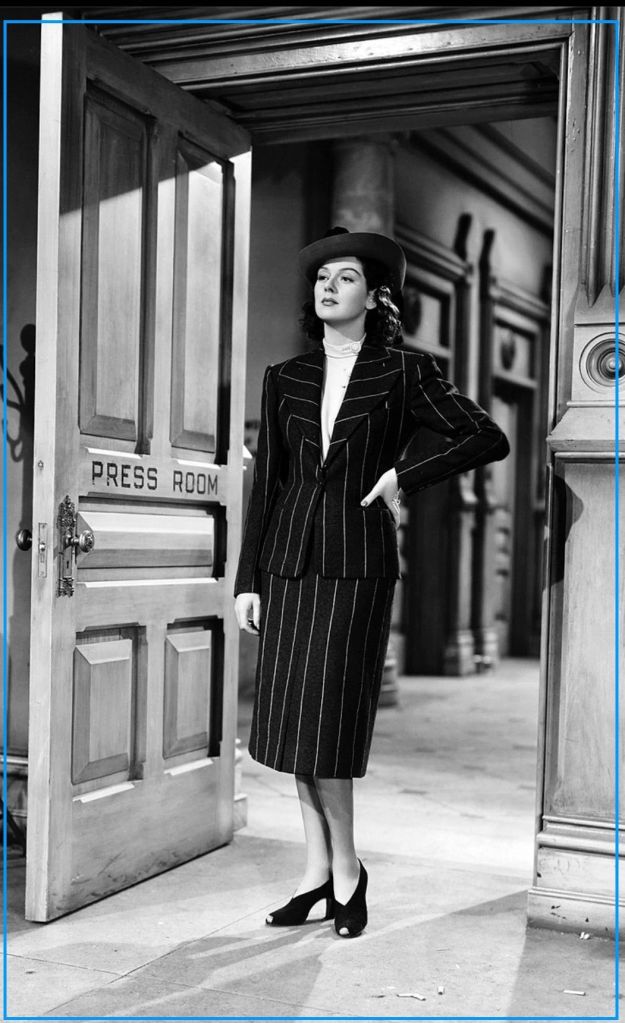

The film opens with a winking title card before plunging into the chaotic offices of The Morning Post: phones ring, papers fly, copy boys race through hallways. And then Hildy Johnson (Rosalind Russell) enters, and the noise briefly halts. Admired by her colleagues as both leader and friend, she has returned not for them but for one man: Walter Burns (Cary Grant), the editor-in-chief of the paper—and her ex-husband. Hildy plans to leave journalism behind, marry mild-mannered insurance salesman Bruce Baldwin (Ralph Bellamy), and settle into domestic life. Walter, determined to stop her, tricks her into covering one last story: the impending execution of Earl Williams, a meek man condemned for killing a Black policeman. Walter insists Williams is innocent, claiming the city’s corrupt politicians want the execution carried out to shore up support from Black voters.

While Hildy pursues the story, Walter schemes to prevent Bruce from whisking her away to Albany. He even frames Bruce for theft, landing him in jail until Hildy bails him out. Fed up, she quits—only to be pulled back in when Earl Williams escapes, her reporter’s instincts overriding her resolve. Walter promptly frames Bruce again, sending him straight back behind bars.

The press room erupts in frenzy when Williams suddenly climbs in through the window. Thinking fast, Hildy hides him inside a rolltop desk. At the same time, a messenger arrives at the mayor’s office carrying the governor’s reprieve for Williams. Determined to see the execution proceed, the corrupt mayor bribes the man to keep the pardon secret until it is too late.

Mrs. Baldwin, Bruce’s mother, bursts into the press room after escaping a kidnapper Walter sent. She tells everyone there—including the mayor—that Hildy is hiding Williams in the desk. Williams is taken back to jail, and Walter and Hildy are arrested for helping him escape. Just then, the messenger returns with the pardon, saying he refused the mayor’s bribe. Walter uses this to blackmail the mayor into letting him and Hildy go free.

Walter tells Hildy she is free to leave with Bruce for Albany, but this only unsettles her—she realizes she still loves Walter and cannot imagine abandoning her life as a reporter. When Bruce phones to say he has been arrested again, this time for passing counterfeit bills Walter planted on him, Hildy recognizes that Walter never meant to let her go. Relieved, she accepts his proposal, and he promises the Niagara Falls honeymoon they never had. But when news of a strike in Albany arrives, Hildy agrees to honeymoon there instead, knowing full well Walter will never change.

In the end, Hildy’s dream of a quiet life with Bruce vanishes. Swept back into the thrill of the chase, she accepts that she belongs as much to the newsroom as to Walter. Their honeymoon is instantly postponed for the next big scoop, confirming that for both of them, journalism will always eclipse domesticity.

His Girl Friday races forward with overlapping dialogue at 240 words a minute, creating a musical rhythm of speech. Hawks set the pace, but Rosalind Russell electrifies it, improvising constantly to deliver a witty, confident performance that makes Hildy the film’s driving force. Feeling her lines were weaker than Cary Grant’s, Russell secretly hired a writer to punch up her dialogue, slipping in jokes—only Grant noticed, greeting her each morning, “What have you got today?” Some of her ghostwritten lines even appear in the restaurant scene, unique to the film.

The restaurant sequence was notoriously tricky: the dialogue was so rapid that the actors barely had time to eat, and Hawks’s single-camera setup, coupled with improvisation, stretched filming from two to four days. Russell’s makeup was carefully shaded to compensate for her less sharply defined jawline and maintain a youthful look. Hawks encouraged bold, unpredictable performances and allowed playful breaks of the “fourth wall,” like Grant’s unscripted glance at the camera, though not all made the final cut.

Hawks explained to Peter Bogdanovich that the overlapping dialogue mirrored real conversation: “We wrote the dialogue in a way that made the beginnings and ends of sentences unnecessary; they were there for overlapping,” capturing the natural rhythm of argument and rapid-fire reporting.

Russell’s Hildy is torn between Bruce’s dull stability and Walter’s thrilling amorality, matching Grant’s charm and scheming with equal force—their verbal sparring drives the film. Though tragedy hovers at the edges, the tone stays brisk, mocking the press’s reckless pursuit of headlines. Only Mollie’s furious outburst cuts through, until Hildy’s sardonic “Gentlemen of the Press” seals the irony.

Hildy Johnson is a sharp, ambitious woman torn between Bruce’s stability and Walter’s dangerous charm. Walter’s ruthless tricks don’t drive her away; instead, the Earl Williams case rekindles her true passion—reporting. Once the story breaks, Albany and Bruce vanish from her mind, and even his repeated arrests no longer matter. A quiet domestic life isn’t for Hildy: she is a “newspaper man” at heart. With Walter, she can be both wife and reporter, though their honeymoon is quickly postponed for the next big scoop—proof that journalism, not romance, always comes first.

After Williams’ escape, the film shifts to rapid, sub-second shots as the newsroom springs into action. Hildy gradually rejoins the chaos—she sheds her Albany coat, picks up the phone, and rushes out with the reporters’ energy. Fast editing, speeding gates and cars, and a contrasting siren highlight the newsroom’s frantic pace, while Hildy’s “HEY!” marks her full return. Hawks uses timing, continuity, and shifting focus to contrast dull domesticity with the thrilling frenzy of reporting.

Walter Burns remains manipulative—framing Hildy’s fiancé and orchestrating a kidnapping—yet persuades her to remarry him. Their reunion shows no romance; honeymoon plans are abandoned for the next story. Cary Grant matches the film’s rapid pace with sharp wit, playful improvisation, and self-referential jokes—like calling Ralph Bellamy “that fellow in the movies” and naming himself “Archie Leach”—making Walter both scheming and irresistibly entertaining.

Joseph Walker, Cinematographer was responsible for how the film looked visually, camera placement, lighting, shot composition, and movement. His work supported Howard Hawks’ famously fast-paced, overlapping dialogue by using longer takes and fluid camera movement, allowing scenes to play out without excessive cutting. He also had to manage the challenge of keeping multiple actors in frame during rapid-fire exchanges, maintaining clarity and visual rhythm.

Gene Havlick, editor’s role was crucial in shaping the film’s snappy pacing. His Girl Friday is renowned for its lightning-quick delivery, with characters often speaking over each other. Havlick had to cut the footage so that the overlaps felt natural yet comprehensible, preserving the comic timing while ensuring the audience could follow the story. His editing keeps the momentum going almost without pause, matching Hawks’ vision of a rapid, press-room energy.

Photos courtesy Google. Excerpts taken from Google.