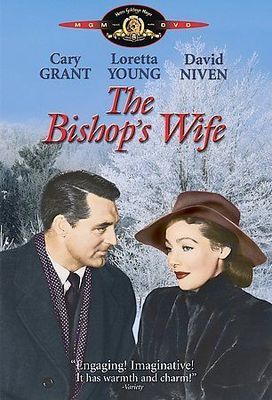

The Bishop’s Wife (released in the UK as Cary and the Bishop’s Wife) is a 1947 American Christmas romantic fantasy comedy directed by Henry Koster. Starring Cary Grant, Loretta Young, and David Niven, the film tells a debonair angel descends to Earth to assist an Episcopalian bishop and his neglected wife, guiding them through their struggles to raise funds for a new cathedral while reminding them of the true spirit of faith and love. Adapted by Leonardo Bercovici and Robert E. Sherwood from Robert Nathan’s 1928 novel, the film blends warmth, humor, and gentle spirituality into a holiday classic.

Bishop Henry Brougham is consumed with the challenge of raising funds for a grand new cathedral, a task that strains his marriage and distances him from his devoted wife, Julia. In his desperation, he prays for divine guidance, and his plea is answered by the arrival of Dudley, a debonair angel who discloses his true identity only to the bishop.

Dudley’s true mission, however, is not to help build a cathedral but to offer spiritual guidance. Henry’s single-minded obsession with fundraising has blinded him to the needs of those closest to him, leaving Julia and their young daughter, Debby, feeling neglected. With quiet charm, Dudley rekindles warmth in the Brougham household, reminding Julia of the joy and companionship she once shared with her husband and showing Henry that his true duty lies not in stone and mortar but in nurturing love, faith, and human connection.

Everyone, except Henry, falls under Dudley’s spell—even the skeptical Professor Wutheridge, who warms to the angel’s easy charm. But as Dudley devotes more time to lifting Julia’s spirits, he discovers an unexpected complication: he is drawn to her himself. Julia, touched by his kindness, begins to blossom under his attention, while Henry grows increasingly jealous and resentful of his heavenly guest. In a moment of candor, Henry confides in Professor Wutheridge, revealing Dudley’s true nature; the professor, recognizing the depth of Henry’s love for Julia, urges him to stand firm and reclaim his place by her side.

Dudley also intervenes with wealthy parishioner Agnes Hamilton, whose fortune Henry has been counting on for the cathedral. With gentle persuasion, Dudley convinces the lonely widow to redirect her generosity toward the poor, urging her to provide food and clothing for those in need rather than finance an edifice of stone. While Mrs. Hamilton responds with warmth and gratitude, Henry is left dismayed, seeing his vision of the cathedral slipping further out of reach.

Throughout his stay, Dudley reveals his angelic powers in quiet yet wondrous ways. He enables Julia and Sylvester, a friendly taxi driver, to glide across the ice like seasoned skaters, transforms the Broughams’ Christmas tree into a dazzling spectacle within seconds, rekindles interest in an old church by inspiring the boys’ choir, and even delivers Henry’s new sermon by dictating directly to a typewriter—without the bishop’s knowledge. These small miracles not only bring joy to those around him but also highlight the simple, life-affirming pleasures that Henry has overlooked in his pursuit of grandeur.

In time, Dudley’s feelings for Julia surface, and he gently hints at his wish to remain by her side rather than move on to his next assignment. Though Julia does not fully grasp his words, she senses the unspoken longing and quietly tells him it is time for him to go. Before departing, Dudley admits to Henry that it is a rare thing for an angel to envy a mortal. When the bishop demands to know why his cathedral plans have been overturned, Dudley gently reminds him that his prayer had been for guidance, not for the building of stone, and that his true mission was to restore love, faith, and balance to the bishop’s life.

With his mission fulfilled and assured of Julia’s devotion to her husband, Dudley takes his leave, promising never to return but content that his work is complete. As he departs, all memory of him is erased from those he touched. On Christmas Eve, Henry delivers a heartfelt sermon—believing it to be his own—unaware that the words were Dudley’s gift, guiding his flock back to the true meaning of faith, love, and service.

The film was directed by Henry Koster, whose light touch and skill in blending humor, fantasy, and sentiment gave the story its enduring charm and helped establish it as a beloved Christmas classic. His direction of film reflected his signature style—warm, character-driven storytelling marked by gentle pacing, graceful performances, and a balance of whimsy with emotional sincerity. Koster’s ability to draw out both the charm of Cary Grant and the poignancy of David Niven helped the film strike its delicate balance between comedy, romance, and spiritual reflection, ensuring its lasting reputation as a holiday classic.

Cary Grant charms as Dudley, the angel who guides Julia while Henry struggles with work—but his interventions, especially the whimsical ice-skating scene, border on manipulative and ethically murky. While performances and humor are solid, the film’s moral ambiguities and dated tone make it less compelling today, and its reputation as a holiday classic feels overstated.

David Niven’s Bishop exudes reserved grace, while Loretta Young blossoms, her scenes with Dudley, her husband, and daughter radiating humanity. Supporting performances by Gleason, Woolley, Lanchester, Cooper, and Grimes enrich the tapestry. Subtle miracles, character-driven storytelling, and a perfectly integrated score make The Bishop’s Wife a luminous, heartfelt classic that celebrates small wonders over spectacle.

The Bishop’s Wife was warmly received by critics and audiences alike, praised for its charm, gentle humor, and heartfelt message. Reviewers highlighted Cary Grant’s effortless charisma as the angel Dudley, Loretta Young’s graceful presence as Julia, and David Niven’s nuanced portrayal of a bishop torn between duty and devotion. The film’s blend of romance, fantasy, and spiritual reflection made it stand out among postwar Hollywood productions, with many noting its uplifting tone during a period of lingering austerity. Over time, it has come to be regarded as one of the quintessential Christmas classics, frequently revisited during the holiday season for its themes of love, generosity, and rediscovery of faith.

At the 20th Academy Awards, the film earned five nominations, including Best Motion Picture (Samuel Goldwyn Productions), Best Director (Henry Koster), Best Film Editing (Monica Collingwood), and Best Scoring of a Dramatic or Comedy Picture (Hugo Friedhofer). It won the Oscar for Best Sound Recording, awarded to Gordon E. Sawyer. The film also garnered praise from contemporary critics for its production values, music, and innovative use of fantasy elements within a romantic narrative. Today, it remains celebrated not only as a showcase of its stars’ talents but also as a timeless reminder of the true spirit of Christmas.

Photo courtesy Google. Excerpts taken from Google.