The Pride and the Passion is a 1957 American Napoleonic-era war film in Technicolor and VistaVision, released by United Artists. Produced and directed by Stanley Kramer, the film stars Cary Grant, Frank Sinatra, and Sophia Loren, with Theodore Bikel and Jay Novello in supporting roles.

The story follows a British Royal Navy artillery officer assigned to retrieve a massive siege cannon from Spain and deliver it to British forces. Before it can be handed over, however, the leader of the Spanish guerrillas insists on dragging the weapon across 1,000 kilometers (620 miles) of rugged terrain—rivers, plains, and mountains—in order to use it in the recapture of Ávila from the French occupiers. Much of the film focuses on this grueling journey, marked by constant danger from French patrols, while a parallel storyline unfolds in the rivalry between the two male protagonists for the love of the Spanish woman Juana (Sophia Loren).

The screenplay, written by Edna Anhalt and Edward Anhalt and loosely adapted from C. S. Forester’s 1933 novel The Gun, was later revised in part by Earl Felton (uncredited). The film’s score was composed by George Antheil, and the striking opening title sequence was designed by Saul Bass.

During the Peninsular War, Napoleon’s armies move quickly across Spain, forcing the Spanish soldiers to retreat. In their hurry, they leave behind a giant siege cannon, stuck in a deep valley because it is too heavy to move. The French know the cannon is very valuable, so they send cavalry to capture it. To stop them, a British captain is sent to Spain on a mission to save the cannon.

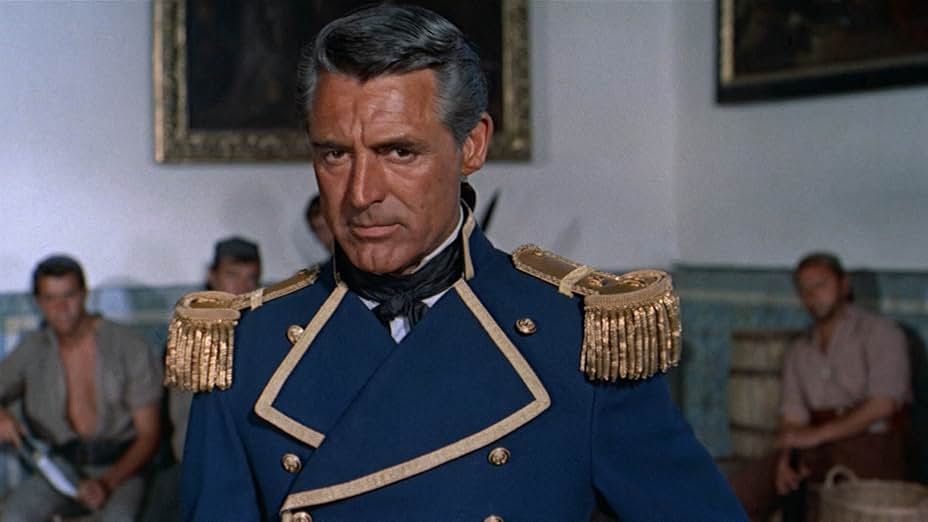

At its core, the film follows a British officer sent to Spain to keep a massive, one-of-a-kind cannon out of Napoleon’s reach. Cary Grant plays Captain Anthony Trumbull, a Royal Navy officer with no backup, relying only on his supposed fluency in Spanish (which the audience never actually hears), his charm, and sheer determination. His uneasy ally is Miguel, a fiery guerrilla leader played by Frank Sinatra, whose hatred of the French drives his every move. Miguel agrees to help Trumbull move the giant cannon to a British-controlled port, but only if it is first turned against the walls of Ávila, a city he is desperate to reclaim from French control.

The setup sparks constant tension: Grant’s refined, cautious officer clashes with Sinatra’s impulsive patriot, their partnership strained not only by the fate of the cannon but also by the presence of Juana, Miguel’s mistress, who finds herself drawn to Trumbull. The result is a tale that blends wartime intrigue with personal rivalry, making the journey less about the weapon itself and more about the battle of wills and hearts that surround it.

Meanwhile, in Ávila, the cruel French commander General Jouvet grows desperate to find the cannon. To force the townspeople to talk, he orders ten Spanish hostages to be executed each day until the weapon is handed over. What he doesn’t know is that Miguel’s guerrillas already have the cannon and are dragging it on a long, painful journey across rivers, mountains, and plains, always followed by French soldiers trying to stop them.

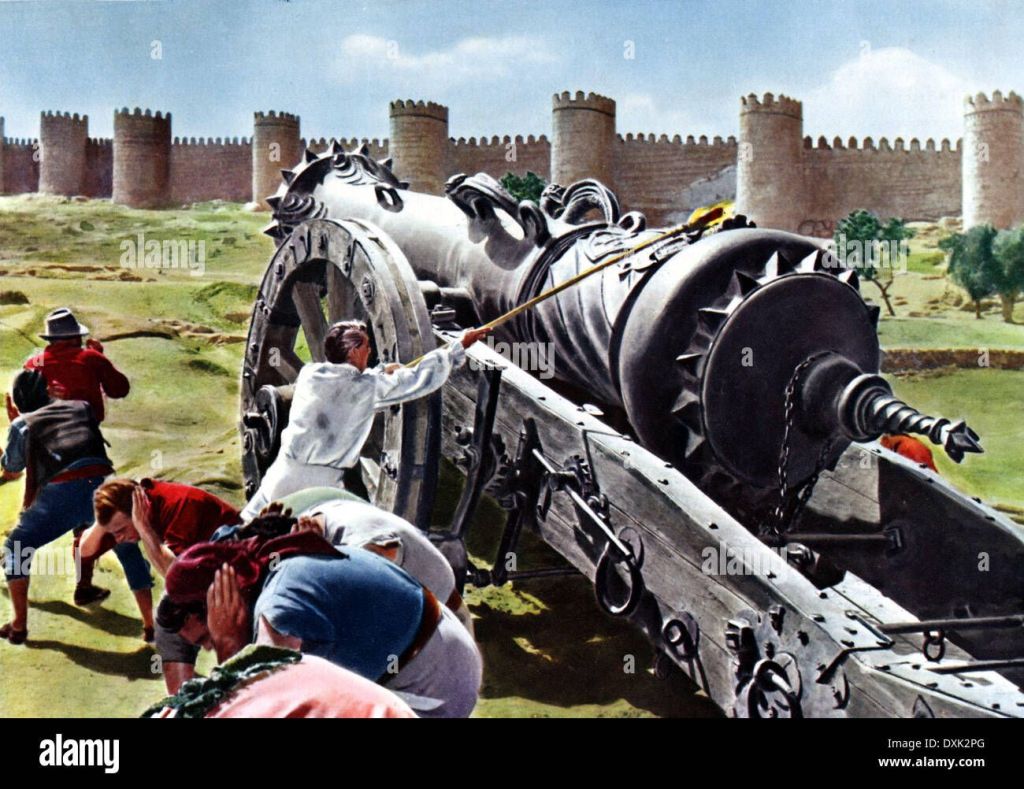

The cannon itself almost becomes a character in the film. Sometimes it looks obviously fake, like a wooden prop, but other times it feels heavy and real. What makes The Pride and the Passion stand out from other war films is how seriously it treats the cannon—not as a thrilling adventure piece, but as a burden. The movie shows how massive it is, how often it breaks, and how much effort it takes to move it. The drama is in the struggle: pulling it from a ravine, crossing rivers, sneaking past an enemy camp, climbing mountains, and hiding it in a city to repair it without the French noticing.

The guerrilla band, now joined by many local recruits, faces a near disaster when Jouvet positions French artillery to block the narrow mountain pass they must cross. A fierce battle follows, and though the guerrillas suffer heavy losses, the help of the local people allows them to push through. The victory comes at a cost: the massive cannon, jolted during the fighting, tumbles down a hillside and is damaged, partly coming off its transport carriage.

The battered cannon is finally taken into a cathedral, where the guerrillas secretly repair it. To sneak it past French patrols, they disguise the huge weapon as a beautiful religious float and move it during a Holy Week procession. The plan succeeds, but not without danger—French officers hear the cannon might be in the cathedral. When they rush to check, however, the cannon has already been repaired and moved, leaving no sign it was ever there.

When the cannon finally arrives at the guerrilla camp on the plains outside Ávila, they begin preparing for the final attack. The city is strongly defended, with massive stone walls, eighty cannons, and a large French garrison. Trumbull warns the guerrillas that at least half of them will probably be killed by the French artillery and rifle fire. Later, he asks Juana not to fight, but she refuses. She has already endured the long, hard journey and wants to take part in the final battle, so she marches with the men the next day.

As the final attack begins, Trumbull fires the massive cannon again and again, its heavy iron shots smashing against Ávila’s high walls. Slowly, part of the fortifications collapses, creating a breach. Despite heavy losses from French fire, the guerrillas rush through the gap and defeat the defenders. General Jouvet is killed, and the last French soldiers in the town square are wiped out.

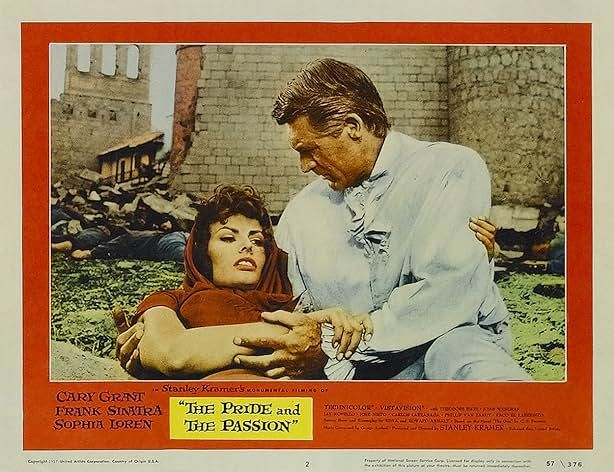

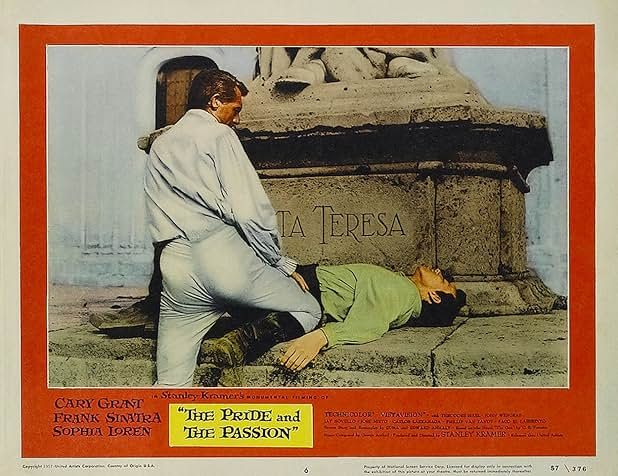

During the battle, Juana is fatally wounded. Trumbull finds her in her last moments and says a sorrowful goodbye. He then carries Miguel’s body to the foot of a statue of Saint Teresa, Ávila’s patron saint, honoring the guerrilla leader’s sacrifice. With the city free, Trumbull secures the cannon for its trip to England. But as he leaves Ávila, he is weighed down by the memories of lost love, fallen comrades, and the high cost of victory.

Stanley Kramer’s The Pride and the Passion (1957), Adapting C.S. Forester’s novel The Gun, Kramer brought together three of the era’s most prominent stars, Cary Grant, Frank Sinatra, and Sophia Loren, promising romance, spectacle, and dramatic weight on an epic scale. Its lavish production values and moments of genuine power, the film emerges as an uneven war drama that struggles to match its physical grandeur with emotional conviction.

Kramer uses Spain’s landscapes and the massive cannon as both spectacle and symbol, though the long march often feels repetitive and sluggish. Despite production troubles, Stanley Kramer earned a DGA nomination for staging battles with thousands of extras and depicting the brutal reality of cannon warfare. The deadly journey to Ávila ends without triumph, as most characters perish—true to Kramer’s style of unsettling audiences and forcing reflection.

Cary Grant plays Captain Anthony Trumbull, a British officer sent to Spain to secure the giant cannon. His performance is calm, charming, and confident, but also rather safe, he doesn’t really take risks as an actor. Grant’s character is meant to be clever and capable, yet he rarely shows real flaws or makes mistakes, which makes him less interesting at times. Grant delivers a sort-of British accent that works. Grant is likable and reliable on screen.

Frank Sinatra plays Miguel, a fiery Spanish guerrilla leader who hates the French. He is brave, impulsive, and determined to reclaim Ávila. Sinatra brings energy and charisma to the role, giving Miguel a strong personality that contrasts with Cary Grant’s calm, controlled officer. His performance makes the guerrilla leader feel real and passionate, even if the story sometimes forces him into predictable heroic moments.

Sophia Loren plays Juana, Miguel’s mistress, who is courageous and loyal. She is also drawn to Trumbull, creating a subtle love triangle. Loren brings warmth, beauty, and emotion to the role, giving Juana depth as a character who is both independent and caring. Her presence adds tension and emotional stakes to the story, especially during the dangerous journey and the final battle.

Critical response was mixed. Variety praised the film’s scale and production, particularly the panoramic battle scenes and the struggle to move the cannon. In contrast, Isabel Quigly of The Spectator criticized the script, Cary Grant’s performance, and the overpowering music, noting that while some landscape shots impressed, the film overall was long-winded and lacked excitement.

Photo courtesy Google. Excerpts taken from Google.