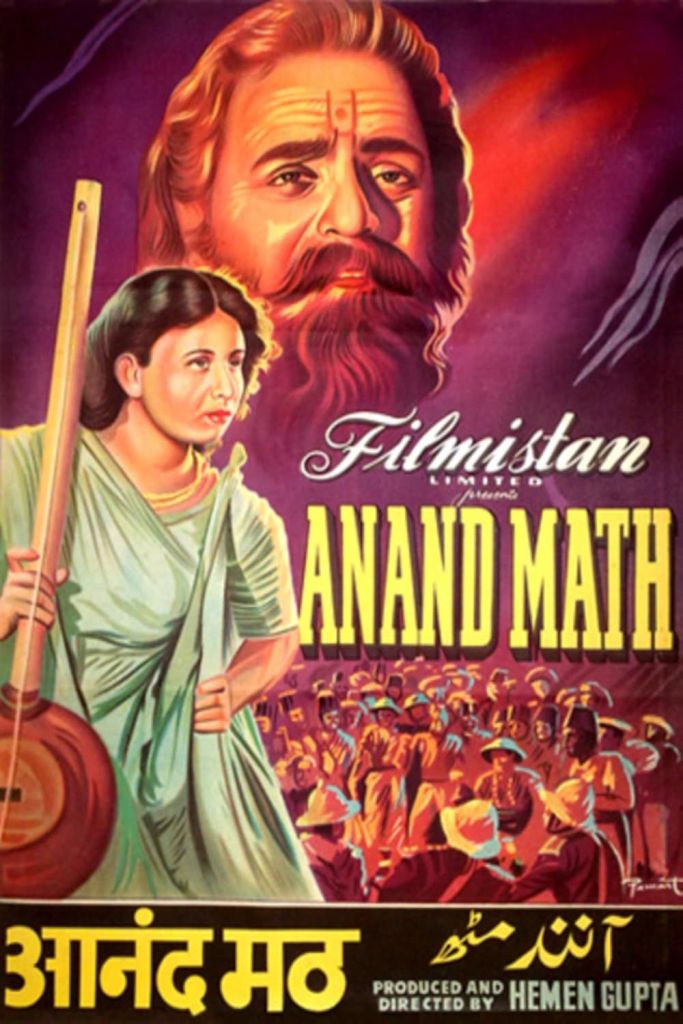

Anand Math is a 1952 Indian Hindi-language historical drama film directed by Hemen Gupta. The film is based on the famous Bengali novel Anandamath, written in 1882 by Bankim Chandra Chatterjee.

Both the novel and the film are set against the backdrop of the Sanyasi Rebellion that took place in Bengal in the late 18th century. During this uprising, sanyasis and fakirs in northeastern India revolted against British rule. At a time when the region was reeling under severe famine and acute food shortages, the British authorities continued their ruthless exploitation. The rebellion, as portrayed in the film, arises from this injustice and oppression.

Satyanand (Prithviraj Kapoor), deeply anguished, questions whether he will ever live to see his motherland free. A disembodied voice answers that freedom will surely come, but at a terrible cost. When Satyanand asks if that cost is his life, the voice replies that life is cheap; what is truly required is complete devotion to the motherland. The voice then recalls the devastating famine of 1770, in which more than half the population of eastern India perished. At the same time, the British East India Company was relentlessly collecting revenue, while Nawab Mir Jafar, lost in luxury and excess, remained indifferent to the suffering of his people. The message is clear: neither natural calamities nor injustice spare anyone—not even the rich.

The story then turns to Mahendra Singh, once an immensely wealthy landlord. During the famine, hundreds are dying of hunger, disease, and British atrocities. In search of food and survival, Mahendra is forced to abandon his grand mansion and migrate with his wife Kalyani and their young daughter. His vast wealth proves useless—he cannot even obtain a single drop of milk for his child. Like countless others, they join the masses fleeing their homes in desperation.

During their journey, Mahendra shelters his wife and daughter in the ruins of a deserted building in the forest and goes out in search of food. In his absence, a gang of dacoits abducts Kalyani and the child. However, as the dacoits begin to fight among themselves over food, Kalyani manages to escape. Exhausted and on the verge of collapse, she is rescued by Satyanand, who gives her refuge in his ashram.

Satyanand is the leader of a secret group of warrior-sanyasis known as the santaan. He assures Kalyani that Mahendra will be found. Bhavanand is assigned the task of locating Mahendra and bringing him to the ashram, while Jivanand leads the attacks against the British. These sanyasis wage a disciplined and organised struggle against the British while also helping the poor in whatever way they can.

When Mahendra returns to the ruins, he finds his wife and daughter missing and is deeply distressed. At the same time, soldiers of the East India Company arrest him, mistaking him for a dacoit. Seeing this, Bhavanand deliberately allows himself to be captured as well. Just then, Jivanand and his companions attack the soldiers. In the confusion, Bhavanand helps Mahendra escape, but Mahendra does not feel grateful. He assumes they are dacoits themselves and wants nothing to do with them.

Bhavanand explains to Mahendra that they are santaan, children of the motherland, fighting for her freedom. Mahendra is still not fully convinced, but he agrees to accompany them to the ashram. There, Satyanand shows him the three forms of the Mother: Jagaddhatri, as she once was; Kali, as she is now; and Durga, as she will be in the future. Satyanand then reunites Mahendra with Kalyani.

Meanwhile, the British officers are enraged by the attack on their forces. When a British officer is killed, they demand compensation from the Nawab and warn him of serious consequences. The Nawab issues an order that the santaan must be captured, dead or alive. However, the group is already aware of this through their spies.

Mahendra and Kalyani leave the monastery, but Mahendra cannot ignore the call of the Mother. The vision of the Goddess has deeply affected him. Kalyani understands and tells him that it is the voice of the Goddess and should not be turned away from. She thinks of taking poison, but Mahendra stops her.

Hearing Mahendra’s cries, Satyanand arrives, but both of them are captured by the soldiers. While being taken to the barracks, Satyanand sings a devotional song. Jivanand realises that the song is actually a secret message. He immediately begins searching the forest. Guided by the sound of a crying child, he finds Kalyani lying unconscious. Believing her to be dead, he takes the child with him. Later, Bhavanand discovers that Kalyani is alive and ensures that she is taken to a physician.

Jivanand leaves the child with his sister, but his heart is torn between his past love and the vow he has taken as a sanyasi. The next day, the santaan launch an attack to free Satyanand. They succeed, but at a heavy cost, as many of their comrades are killed. Grieved by these losses, Satyanand declares that greater strength and cannons are now needed to fight the British, and that harsh measures must be adopted for the sake of the goal.

Leaving the responsibility of the monastery in the hands of Bhavanand and Jivanand, Satyanand departs. He promises to find skilled craftsmen and send them to Padachinha, where Mahendra’s house will be converted into a factory for manufacturing arms and ammunition. Before leaving, he warns them that if anyone has committed a sin, knowingly or unknowingly, they must wait for his return before attempting any atonement.

Meanwhile, Mahendra is initiated into the monastery. Satyanand grows suspicious of a young man who has arrived with him and gives him the name “Navinanand.” Soon it is revealed that the young man is actually Shanti in disguise. She confronts Satyanand with direct questions—what exactly constitutes a sin, and whether the penance demanded for it is truly justified. Her questions unsettle Satyanand, yet he is moved by her emotional plea and allows her to remain in the monastery.

Both Jivanand and Bhavanand are inwardly tormented. Even though Shanti now lives as “Navinanand,” Jivanand cannot distance himself from her. Bhavanand, too, is unable to forget Kalyani. A troubling thought takes hold of them—if atonement for sin ultimately means death, then what difference does committing one more sin make?

Throughout this period, the santaan continue to carry out carefully planned attacks against the British, and in response, British oppression grows harsher. Eventually, Warren Hastings is sent to India. The Nawab is left with no real authority; he becomes merely a puppet, while all power is exercised by the British from afar.

Anand Math is a powerful drama with religious overtones but a fundamentally political core. During the freedom struggle, it not only stirred nationalist sentiment but also gave India its national song, “Vande Mataram.” Bankim Chandra Chatterjee imagined the nation as a Mother Goddess, whose chains can be broken only through the supreme sacrifice of her children. By placing the goal of freedom above personal life, Anand Math glorifies the sacrifices that men and women of that era were compelled to make. With strong performances by Prithviraj Kapoor, Pradeep Kumar, Bharat Bhushan, Geeta Bali, and Ajit, the film becomes not merely an intense nationalist statement but also a deeply personal one. The fundamental question it poses is simple yet profound: what comes first, the nation or personal relationships? Both the novel and the film arrive at the same conclusion: for the greater good of the country, personal ties must be sacrificed.

In Anand Math, “Vande Mataram” is not used merely as background music or a patriotic song; it is the very soul of the narrative. Written by Bankim Chandra Chatterjee in the novel, the song envisions the motherland as a divine figure—wounded and enslaved, yet eternally worthy of worship. In the film, this idea is powerfully realised through visuals, music, and storytelling, making Vande Mataram the emotional and ideological heart of the story.

In the film, “Vande Mataram” functions as the rallying cry of the sanyasi santaan. The song calls for a struggle for freedom, but at the same time it makes the cost of that struggle unmistakably clear—sacrifice, personal suffering, and, at times, death. Whenever the song is heard on screen, it does more than stir patriotic fervour in the audience; it also gives voice to the inner conflicts of the characters. At its core lies the readiness to surrender everything for the motherland.

The song is especially closely tied to the journeys of Mahendra, Jivanand, and Satyanand. For Mahendra, Vande Mataram becomes the call that draws him from personal grief toward national duty. For Jivanand, it symbolises the tension between love and obligation. And for Satyanand, it is a mantra of asceticism, severe discipline, and the reminder of ultimate sacrifice.

Rendered in the voices of Hemant Kumar and Lata Mangeshkar, Vande Mataram attains an emotional and spiritual height in the film. It goes beyond being merely a patriotic song and firmly establishes the idea of the motherland as a living, suffering presence, a mother awaiting liberation. This is why, in Anand Math, Vande Mataram becomes a powerful narrative force: it drives the story forward, shapes the characters’ decisions, and plants a deep sense of national consciousness in the minds of the audience.

The song “Jai Jagdish Hare” is based on the Dashavatar Stotram from Jayadeva’s Gita Govinda. In the film, five verses from this hymn are used to depict five incarnations of Vishnu—Matsya (the fish), Vamana (the dwarf), Rama, Buddha, and Kalki. The presentation of this song is especially striking. The voices of Geeta Roy and Hemant Kumar continuously overlap, creating a unique auditory experience. Hemant Kumar’s chanting of the shlokas begins in a very soft tone, as he sings for Prithviraj Kapoor, who is at some distance, after which Geeta Roy steps in for Geeta Bali with “Keshava, dhrita meena shareera…”. Initially, it feels like a conventional devotional duet, but it soon takes an extraordinary turn. From that point on, there is not a single moment when both singers are not singing—yet they sing entirely different lines throughout. It feels as though two distinct and separate songs are being sung simultaneously, creating a rare, deeply spiritual, and cinematic experience.

In a BBC World Service poll conducted in 2003 across 165 countries, Vande Mataram, was ranked second among the “Top Ten Songs of All Time in the World.”

📸 Photo courtesy: Google ✍️ Excerpts: Google