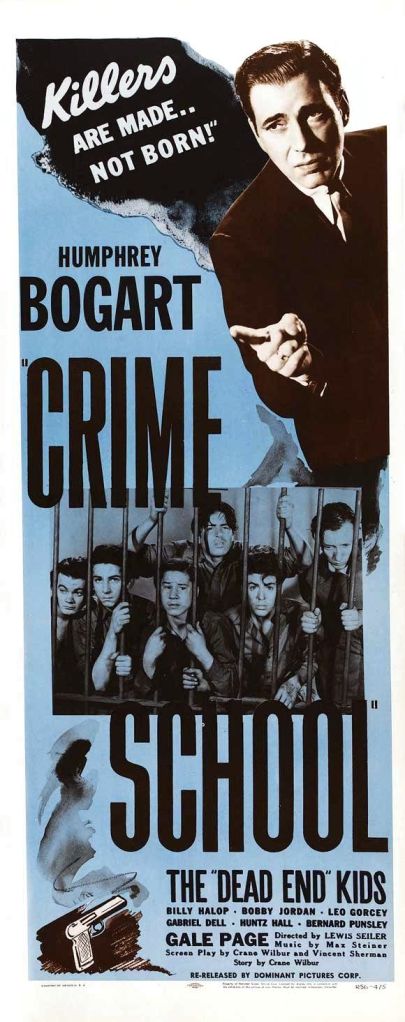

Crime School is a 1938 American crime drama produced by Warner Bros., based on the group of boys known as the “Dead End Kids.” The film is directed by Lewis Seiler, with story and screenplay by Crane Wilbur. It stars the Dead End Kids, Humphrey Bogart, and Gale Page in leading roles. The story revolves around a group of young boys who grow up in poor neighborhoods and are hardened by harsh street life. Reform school, discipline, injustice, and the possibility of redemption form the core themes of the film. Arthur Todd’s realistic cinematography, Terry Morse’s effective editing, and Max Steiner’s restrained musical score enhance the film’s impact. Crime School is not merely a crime story; it is a film that reflects the social realities of its time and raises important questions about juvenile reform.

The plot begins when members of the Dead End Kids, Frankie, Squirt, Spike, Goofy, Fats, and Bugs—are negotiating with a junk dealer. The boys demand twenty dollars from him, but he is willing to give only five. Enraged by this, Spike strikes the dealer violently on the head, knocking him unconscious. All the boys are subsequently arrested and brought before the court. During the trial, none of them is willing to reveal who actually committed the assault, and as a result, the judge sentences all of them to a reform school.

The reform school is run by a strict warden, Morgan, who enforces an extremely harsh and cruel discipline. When Frankie attempts to escape, Morgan has him flogged. Mark Braden, the state official in charge of reform schools, visits the institution and observes clear evidence of Morgan’s subtle yet brutal methods, such as serving inferior-quality food to newly admitted boys.

Later, he visits Frankie in the hospital ward, where Frankie has received no treatment at all and the doctor is drunk. In an effort to improve conditions, Braden dismisses the doctor, Morgan, and four guards who are former criminals.

Mark Braden says,

“Morgan, this place you are running is a school, not a prison. You are dealing with boys here, not hardened criminals. Morgan, have you ever been beaten with a whip? I had been hearing a great deal lately about the conditions here, but I never imagined they were this terrible. From everything I have seen since I arrived, I am convinced that sixty percent of your inmates go on to become criminals precisely because of the way you treat them. By treating them as you do and keeping them in such miserable conditions, you cannot expect them to respect law and order. Your service ends here, Mr. Morgan. You are dismissed.”

However, he retains the chief guard, Cooper. Braden then takes charge of the reform school himself and, through a sympathetic and humane approach, gains the boys’ trust and cooperation.

Braden says to Cooper, “They must be kept constantly busy with work. Let them clean and paint their own dormitory themselves. That way, they will take an interest in it and develop a sense of responsibility. Perhaps some of them may even turn out to be good painters.”

Later, Braden goes to see the painting done by the boys and encourages them.

Cooper assigns the boys the job of shoveling coal into the boiler room. Exhausted after feeding the coal, the boys sit down there to rest. Just then, a security guard arrives and threatens them, saying, “If you sit around, you won’t get any food.” According to regulations, the temperature is supposed to be kept at seventy-five degrees, but the boys continue shoveling coal nonstop. Gradually, the temperature rises beyond one hundred degrees.

Seeing this, the guard rushes in, realizes the danger, and shouts, “Everyone out of here immediately!” All the boys run out, but in the confusion Squirt is left behind. Suddenly, there is a massive explosion, and the boiler room is engulfed in flames.

At that moment, Braden comes running and anxiously asks the boys, “Is everyone out?” The boys tell him that Squirt has not come out yet. Without a moment’s hesitation, Braden plunges into the raging fire and, risking his own life, rescues Squirt and brings him out safely. This incident clearly reveals Braden’s humanity, courage, and genuine concern for the boys.

Meanwhile, Cooper fears that Braden will discover Morgan’s embezzlement of the food budget, in which Cooper himself could also be implicated. He learns that it was Spike who struck the junk dealer, and he uses this information to blackmail Spike. Cooper forces Spike to tell Frankie that Braden’s kindness is the result of Braden’s romantic involvement with his sister. This is a lie, but it sows doubt in the boys’ minds.

Because of this misunderstanding, the boys escape from the reform school in Cooper’s car, taking his gun with them. They reach Sue’s apartment, and Frankie, carrying the gun, climbs up the fire escape to confront Braden. However, Sue and Braden together clear up Frankie’s misunderstanding, and his suspicions are finally laid to rest.

Meanwhile, Cooper deliberately creates the impression that he has “discovered” the boys’ escape, and Morgan summons newspaper reporters in an attempt to disgrace Braden and have him dismissed from his post. However, Braden himself brings the boys back to the reform school in his car and puts them to bed in their bunks before the Commissioner—whom Morgan has called in along with the police for an inspection—arrives.

Their conspiracy collapses and the deception is exposed. As a result, Morgan and Cooper are arrested. The boys are then released on probation under the supervision of their parents.

When Mark Braden, the Deputy Commissioner, finally understands what has really been going on inside the reform school, his outlook changes. He realizes that children are not born criminals; it is circumstances and the social system that shape them that way. Evidence is gathered against Warden Morgan’s inhumane conduct, and the truth ultimately comes to light. Morgan is punished and the boys receive justice. The court gives priority to rehabilitation over revenge.

Crime School firmly asserts that excessively harsh punishment does not reform children; instead, it makes them worse. With understanding, guidance, and humanity, even children who have strayed into crime can be brought back onto the right path.

Set against the backdrop of Depression-era America, marked by poverty, unemployment, and broken family structures—the film makes it clear that crime is often a product of circumstance rather than an inborn trait. Though the Dead End Kids may appear rude and rebellious, they are also children who question the system and have learned to survive in their own way. Their roughness, inner sensitivity, and refusal to bow to injustice are clearly visible. This is why the audience feels sympathy for them: these boys are not bad, merely lost, and they should be seen not as criminals, but as human beings in the process of being shaped.

Bogart appears in the role of a prison reformer, and this becomes the greatest strength of Crime School. In particular, the relationship that develops between Bogart and Billy Halop forms the true emotional backbone of the film. In the role of Deputy Commissioner Mark Braden, Bogart portrays the prison reformer with remarkable restraint and credibility.

Throughout Bogart’s entire career, there are very few roles in which he appears as a completely honest, decent, and naturally likable man. Here, there is not the slightest trace of anger, jealousy, deceit, selfishness, suspicion, or dishonesty in his character. Seeing him in such a wholly positive role is genuinely pleasing.

The conflict between Warden Morgan and Mark Braden represents a clash of two opposing philosophies. Morgan believes that discipline is achieved through fear, while Braden believes that children cannot be reformed without understanding them. The film clearly takes a stand in favor of Braden’s viewpoint.

Crime School reflects Warner Bros.’ trademark realism. The music is sparse, the sets feel authentic, and the dialogue is direct and fast-paced. The absence of excessive sentimentality makes the film’s impact even stronger.

This film does not merely entertain; it issues a warning. It argues that children cannot be reformed through violence and oppression—only through understanding and guidance can they truly change. The aggression of the Dead End Kids, Bogart’s calm and moral journey, and the film’s direct critique of the system together make Crime School a film that remains worthy of study even today.

📸 Photo courtesy: Google. ✍️ Excerpts: Google.