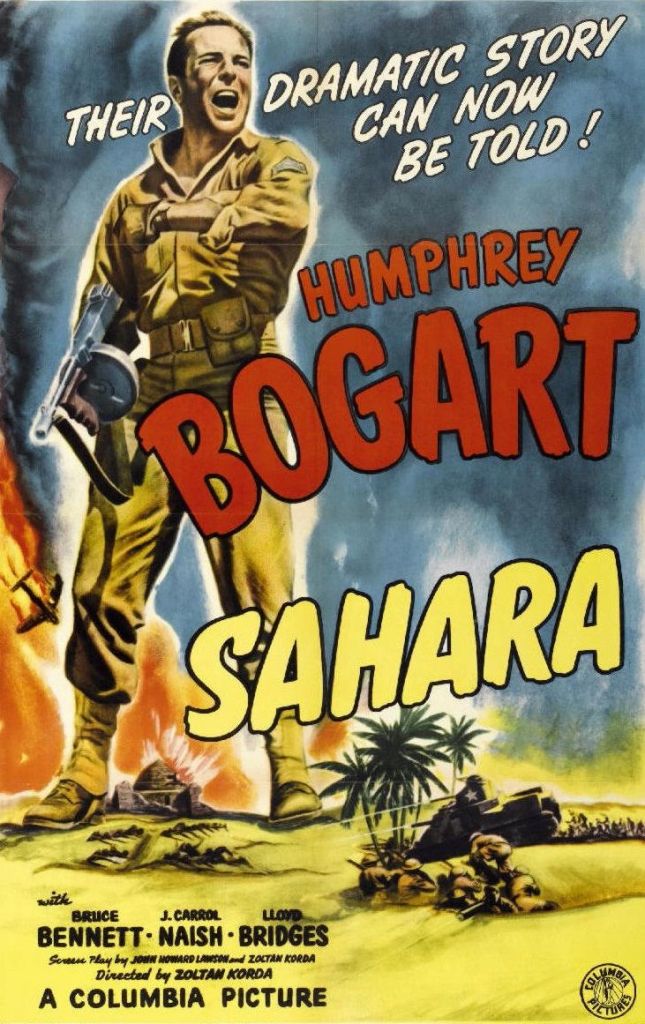

Sahara is a 1943 American war and action film. It was directed by Zoltán Korda and stars Humphrey Bogart as an American tank commander in Libya during World War II. In the story, Bogart and a small group of Allied soldiers find an isolated well in the desert. They have only a small amount of water, but they try to defend the well from a large group of German Afrika Korps soldiers.

The film is based on the novel Patrol by Philip MacDonald and is also inspired by a scene from the 1936 Soviet film The Thirteen by Mikhail Romm. The screenplay was written by John Howard Lawson.

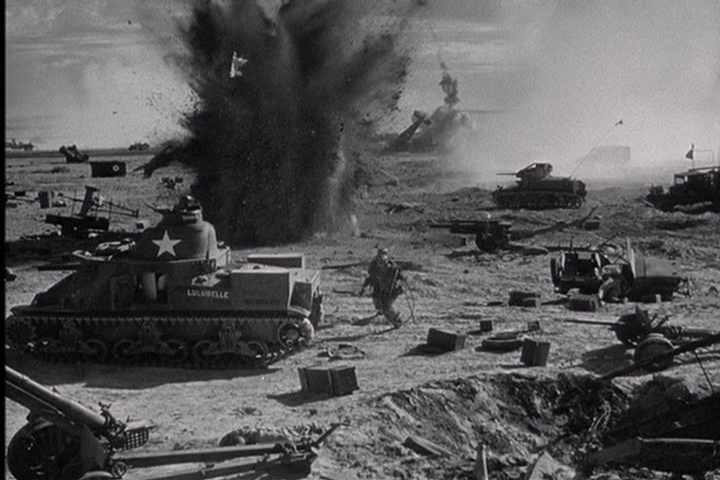

In 1942, the crew of the Lulubelle, an American M3 Lee tank, gets separated from their unit. They were fighting with the British Eighth Army, but after the fall of Tobruk, everyone is forced to retreat from the German forces.

Because they are cut off, Master Sergeant Joe Gunn, the tank commander, and his two men, Doyle and Waco, must travel south across the hot Libyan Desert.

On their way, they find a bombed field hospital. There, they rescue Captain Halliday, a British Army doctor, along with four soldiers from Commonwealth countries and Corporal Leroux, a Free French soldier.

Captain Halliday is the highest-ranking officer, but he knows that Joe Gunn has more experience in desert fighting, so he respectfully gives command to Gunn.

Riding on top of the tank, the group meets Sergeant Major Tambul of the Sudan Defence Force and his Italian prisoner, Giuseppe. Tambul offers to guide them to a well at Hassan Barani. At first, Gunn says the Italian must be left behind, but later he changes his mind and allows Giuseppe to come with them.

On the way, a German fighter plane attacks the tank. The pilot, Captain von Schletow, seriously injures Clarkson, one of the soldiers. The plane is shot down, and the group captures von Schletow.

When they reach Hassan Barani, they discover that the well has no water, and Clarkson dies from his injuries.

Tambul leads the group to another desert well at Bir Acroma, but it has only a small trickle of water. The group collects as much as they can, but soon the well dries up completely.

Then, German scouts arrive in a half-track vehicle. Gunn captures two of them and finds out that a German battalion, very thirsty and badly in need of water, is coming soon.

Gunn convinces his men to stay and fight, so they can delay the Germans while Waco drives the half-track to get help. Gunn lets the two German prisoners go back with a message for their commander: they can trade food for water. Gunn hopes the Germans will believe there is still plenty of water, even though the well is actually dry.

When the German battalion arrives, a tense battle of minds begins between Gunn and the German commander, Major von Falken. Gunn continues pretending that the well has plenty of water, and he changes his offer — now he will trade water for guns.

Von Falken refuses and orders several direct attacks, which weaken Gunn’s group.

During one attack, von Schletow secretly stabs Giuseppe, because Giuseppe speaks against fascism and refuses to help him escape. Before dying, Giuseppe warns Gunn.

Tambul runs after von Schletow and kills him before he can reach the German lines, but Tambul is shot and dies too.

Later, Leroux meets von Falken again to talk, but they reach no agreement. As Leroux walks back to his group, von Falken has him shot in the back. Gunn and his men fire back and kill von Falken.

The Germans launch what looks like their final attack, but instead they suddenly surrender. They drop their guns and crawl toward the well, desperate for water.

Gunn is shocked to see that a German artillery shell had exploded near the well and opened a new water source, making the well fill up again. While the surviving Germans drink, Gunn and Bates, the only two Allied soldiers left alive—take away their weapons.

Later, as Gunn and Bates march the German prisoners east, they meet Allied soldiers who were led there by Waco. The Allies bring good news: they have won the First Battle of El Alamein, successfully stopping Rommel’s Afrika Korps.

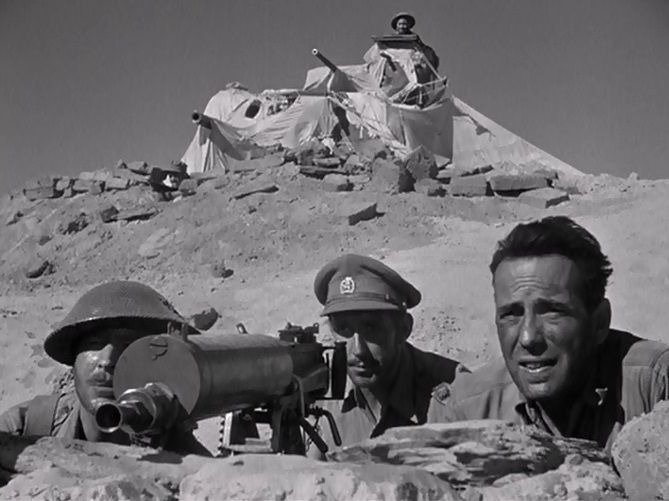

Humphrey Bogart gives a strong and controlled performance as Master Sergeant Joe Gunn in Sahara. His acting is one of the main reasons the film is considered a classic war drama. He plays Gunn as a confident and cool-headed leader who keeps his scattered group of Allied soldiers together in a very difficult situation. Bogart shows Gunn as a real soldier — tired, dusty, stressed, but still responsible. He carefully rations the last bit of water, decides whom to trust, and handles prisoners wisely.

His loud orders, quick reactions, and focused expressions make the military scenes feel real. He looks like an ordinary soldier who becomes a hero because of the situation.

Bogart plays the role with quiet strength. Even in moments of danger and exhaustion, he stays calm and shows true leadership. He avoids overacting and uses a natural, simple style that fits the war setting. His performance shows both the toughness needed to survive the desert and the humanity of a soldier who feels responsible for his men. Critics praised him for his rugged presence, steady courage, and his ability to express emotion without doing too much. This makes his role in Sahara one of his most believable wartime performances.

The cast and crew filmed for eleven weeks in the Anza-Borrego Desert State Park in Imperial County, California, near the Salton Sea. They stayed at the Planter’s Hotel in Brawley, about 50 miles (80 km) from the filming area.

Around 100 soldiers from the U.S. Army’s 4th Armored Division, 84th Reconnaissance Battalion, who were training nearby in the desert, were used as extras in the movie. The film is dedicated to the IV Armored Corps of the Army Ground Forces, the training group that supervised the 4th Armored Division in early 1943. The soldiers stayed in tents at the filming site.

Filming in the desert caused many problems, like sunburn, sandstorms, and extreme heat. Korda brought in 2,000 tons of sand to cover the hard ground. The crew spray-painted the sand and used wind machines to make it look more natural. They also spray-painted shadows on the hills.

The cinematography of Sahara was done by Rudolph Maté, whose black-and-white photography captured the harsh beauty and intense atmosphere of the desert setting. His work helped make the film’s sandstorms, heat, and battles feel real and visually striking. The film was edited by Charles Nelson, who kept the pacing tight and the action smooth, ensuring that the tension and drama built steadily throughout the story. Their combined work contributed greatly to the film’s powerful impact and realism.

Makeup artist Henry Pringle made the actors look sweaty by putting vaseline on their faces and spraying water on top.

This film is a nice and enjoyable adventure movie with good black-and-white photography. The movie is clean, and it shows the American soldiers as morally good and ideal heroes. Since it is a “hero film,” we cannot expect deep moral problems or complex issues, the focus is on inspiring leadership and courage. Also, there are no women characters in the film.

The Boston Globe praised the film, saying it was powerfully acted and emotionally strong. The review noted that there is no love story and no women in the cast—just the harsh reality of war. One of the most emotional scenes, according to the review, is when the Italian prisoner (played by J. Carrol Naish) begs Sergeant Gunn to let him live.

Bosley Crowther of The New York Times focused on Humphrey Bogart, saying he is excellent and tough as always. He compared Sahara to The Lost Patrol and called it a strong and impressive war film.

Otis Guernsey Jr. of the New York Herald Tribune also praised Bogart’s calm, natural acting, calling it perfect for a war movie. He said it was refreshing to see an American soldier who dislikes war but still shows courage and steady resolve. He also praised Korda’s direction, saying the film’s action and visuals were more important than the dialogue.

Actor J. Carrol Naish was nominated for an Oscar for Best Supporting Actor.

The film also received nominations for Best Sound, John Livadary and Best Black-and-White Cinematography, Rudolph Maté.

📸 Photo courtesy: Google. ✍️ Excerpts: Google.