The Big Sleep (1946) is a famous American film noir directed by Howard Hawks – so much so that some critics consider it one of the greatest film noirs ever made. The film is based on renowned crime novelist Raymond Chandler’s first novel The Big Sleep (1939), and its central character is Chandler’s beloved fictional private detective, Philip Marlowe. The screenplay for the film was written by William Faulkner, Leigh Brackett, and Jules Furthman.

In Hawks’s screen adaptation, the role of Philip Marlowe is powerfully portrayed by Humphrey Bogart, and this performance is one of the key reasons for the film’s immense popularity – it became one of the most memorable roles of Bogart’s career. Another major reason for the film’s success is the on-screen romantic pairing of Bogart and Lauren Bacall; the “Bogie and Bacall” chemistry had already won over audiences, and during this period the two had come together in real life as well.

In the story, private detective Philip Marlowe is hired to uncover the secrets troubling the wealthy Sternwood family. What seems like a simple case soon transforms into a tangled web of blackmail, gambling, criminal rackets, and multiple murders.

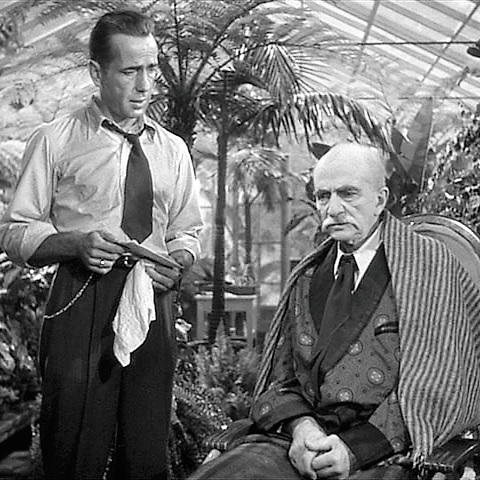

The Big Sleep begins with Los Angeles private detective Philip Marlowe (Humphrey Bogart) being summoned to the luxurious mansion of wealthy, ailing General Sternwood (Charles Waldron). Sternwood is worried about his two troublesome daughters—the wild, flirtatious Carmen (Martha Vickers) and the divorced, sharp-witted Vivian Rutledge (Lauren Bacall). Carmen has taken a personal loan from a bookseller named Arthur Geiger, and Sternwood wants Marlowe to get her out of this mess.

As Marlowe is leaving, Vivian stops him. She believes that her father has hired the detective for another reason altogether—to find Sean Regan, the General’s trusted friend who mysteriously disappeared a month earlier.

Marlowe first visits Geiger’s bookstore, run by Agnes Lozier. From there he follows Geiger’s trail to his house. Just then he hears a gunshot and a woman’s scream. Marlowe rushes inside and finds Geiger dead, while Carmen is unconscious from drugs. A hidden camera is discovered in the room, but its film roll has vanished.

After dropping Carmen safely home, Marlowe returns to the scene—only to find that Geiger’s body is missing. Later that night, he receives another shock: Owen Taylor, the Sternwoods’ chauffeur, has been found dead. His limousine had plunged off Lido Pier into the ocean, and there were signs he had been struck on the head.

The next morning, Vivian arrives at Marlowe’s office. She has received compromising photos of Carmen, along with a blackmail demand for the negatives.

Marlowe returns to Geiger’s bookstore. From there he tails a suspicious car to the apartment of Joe Brody, a small-time racketeer who had previously extorted money from the Sternwoods.

Later, Marlowe spots Carmen again near Geiger’s house. She insists that Brody is the one who killed Geiger. Just then, the landlord—and a dangerous gangster—Eddie Mars arrives, cutting their conversation short.

Marlowe then goes to Brody’s apartment, where he finds Agnes and Vivian. Moments later, Carmen also shows up, demanding her photographs back. She pulls out a gun, but Marlowe disarms her and sends both Vivian and Carmen home.

Brody finally admits that he was behind the blackmail. He had stolen the negatives from Owen Taylor, but he denies killing Taylor. Just then, there’s a knock at the door. Brody opens it—and is shot dead.

Marlowe immediately chases down the killer and catches him. The shooter is Carol Lundgren, Geiger’s former driver. Believing that Brody had double-crossed them, he killed him in revenge. Marlowe phones the police and has Lundgren arrested.

Marlowe then visits Eddie Mars’s casino and questions him about Sean Regan, who is rumored to have run away with Mars’s wife. Mars dodges the questions and instead brings up Vivian’s heavy gambling debts at the casino.

Vivian wins a large sum and asks Marlowe to drive her home. As they leave, one of Mars’s men stages a fake holdup to rob Vivian, but Marlowe knocks the man out.

While driving, Marlowe realizes the truth: Mars had arranged the phony robbery to show that he and Vivian were not secretly working together. Marlowe presses Vivian about her real relationship with Mars, but she refuses to admit anything.

When Marlowe reaches home, he finds the flirtatious Carmen waiting for him. She tells him she never liked Regan, and also reveals that Mars keeps calling Vivian repeatedly. She tries to seduce Marlowe, but he firmly throws her out.

The next day, Vivian visits Marlowe and claims that Regan has been found, he is supposedly in Mexico—and she is going to meet him.

Soon after, Mars has Marlowe beaten up badly, warning him to stop digging any further. Injured and staggering, Marlowe runs into Harry Jones, Agnes’s partner, a small man who sincerely loves her. Jones tells Marlowe that Agnes knows where Mars’s wife is hiding, and she’ll give the information for just 200 dollars.

Marlowe goes to meet him, but he finds Lash Canino, Mars’s hired gun, waiting there. Canino is also looking for Agnes. While Marlowe hides and watches, Canino threatens Jones. Terrified, Jones gives him an address for Agnes. Canino then offers him a “drink,” but it’s poison. Jones dies instantly. Later, it becomes clear that the address Jones gave was fake, a desperate attempt to protect Agnes.

Meanwhile, Agnes phones Marlowe’s office. She tells him she has seen Mona Mars, Eddie Mars’s wife, hiding behind a garage near Realito. Marlowe goes there, but Canino ambushes him. When Marlowe wakes up, he finds himself tied up, with Mona watching over him.

Vivian is also there, and she is the one who frees Marlowe. The moment Marlowe gets hold of a gun, he shoots Canino dead. He then returns to the city with Vivian.

Back in Los Angeles, Marlowe calls Eddie Mars from Geiger’s house, retending he is still in Realito.

Soon, Mars arrives with four gunmen and sets a trap outside. When he enters the house, Marlowe confronts him directly. Marlowe explains that Mars was blackmailing Vivian, because it was Carmen who had killed Sean Regan, and Mars had been covering up the crime. Marlowe forces him out of the house—straight into the line of fire of his own men, who shoot him dead in the confusion.

Marlowe calls the police and lays the entire crime at Mars’s door, tying up the case neatly.

In the end, he tells Vivian that Carmen needs psychiatric treatment. The spark between Marlowe and Vivian, present from the beginning, now grows into a clear, open affection. Vivian admits her mistakes and says, “You can make everything right.”

Thus, after a long, dark, and tangled investigation, the story ends on a gentle, human note, a small beam of light rising from all the shadows.

In The Big Sleep, Humphrey Bogart’s portrayal of Philip Marlowe stands as one of the most commanding performances of his career. His dry wit, cool self-assurance, and sharp, observant gaze bring Marlowe vividly to life. Lines like “You’re not very tall, are you?” and “I don’t mind if you don’t like my manners…” perfectly reflect his icy, razor-edged persona.

Marlowe is tough on the outside yet honest and sensitive within, and Bogart conveys this beautifully through subtle expressions and a calm, controlled voice. His chemistry with Lauren Bacall’s Vivian is pure magic: quick glances, suggestive dialogue, and an effortless, simmering attraction.

Marlowe is not just a clever detective; he is a solitary, wounded man in search of justice. Even amid danger, blackmail, and false leads, he retains his composure and works his way toward the truth. Whether dealing with Carmen or any other character, he instantly reads people, sensing their real intentions beneath their facades.

Overall, Bogart’s performance in The Big Sleep is stylish, intelligent, deeply layered, and arguably a pinnacle of his screen presence. He plays Marlowe not merely as a “detective,” but as a flawed, humane, justice-seeking man.

The Big Sleep was not just a noir film; it was a magical blend of confusion, smoke, and sexual tension. Its plot was so tangled that no one fully understood it—and the answer to one murder remains unknown even today.

Howard Hawks cared less about explaining the story and more about atmosphere: Bogart–Bacall chemistry, shadows, sharp dialogue, and the courage to ignore rules. It was a perfect storm of chaos, accident, and talent that could never come together again. The film was beautiful and sexy, yet confusing—and audiences loved that confusion. They didn’t care about the plot; Bogart lighting a cigarette and Bacall’s single glance were enough. The studio chose not to “fix” the confusion, and that decision became the film’s greatest victory.

Audiences wanted mood and chemistry, not clarity, and that is what made The Big Sleep immortal. William Faulkner, too, emphasized razor-sharp dialogue over narrative logic in the screenplay.

Despite a 25-year age gap—Bogart was 45, Bacall 20, they appeared equal on screen because their real-life affair made the chemistry authentic. Hawks didn’t suppress it; he hid it in subtext. The censors’ rules weren’t broken, but suggestive dialogue, looks, and pauses turned The Big Sleep into one of the sexiest noirs of the 1940s.

Elisha Cook Jr.’s death scene was filmed in a single take, brutal and unsettling—one of the darkest moments in classical Hollywood. The film’s visual inconsistencies were deliberate: Los Angeles was designed not as a logical city, but as a dreamlike labyrinth.

Dorothy Malone’s three-minute bookstore scene became legendary. Minimal music, heavy silence—rain, breathing, footsteps, intensified the tension. The Big Sleep chose atmosphere over clarity, and that became its soul.

This film cannot be remade. It can only be watched, and admired for how something so broken feels so complete. It doesn’t give answers; it asks questions, and 75 years later, we’re still searching for them.

Bogart’s casual gesture of touching his hat wasn’t scripted; it happened naturally and became iconic. The worn fedora was his own. After his death, Bacall kept it safe. It wasn’t just a prop—it was a witness to history.

Finally, on August 31, 1946, Warner Bros. released The Big Sleep to the public, and the film enjoyed tremendous success with both critics and audiences.

Film critic Roger Ebert loved these very elements so much that he wrote:

“Drawing on Chandler’s words, and coloring them with their own voices, Faulkner, Furthman, and Brackett created an extraordinarily memorable screenplay. The audience doesn’t laugh because anything is conventionally funny—they laugh because the lines are so clever and intelligent. Unlike modern crime films that rely heavily on action, The Big Sleep is packed with dialogue; everyone talks constantly, just like in Chandler’s novels. It’s as if all the characters are competing to see who can speak with the most style.”

Time magazine critic James Agee also offered a positive view. He said the film is perfect for those who “don’t particularly care what’s going on or why, so long as the dialogue is tough and the action is hard.” In his opinion, the very confusion of the plot is part of the film’s greatest charm.

Agee called Humphrey Bogart the film’s “most valuable asset.” About director Howard Hawks, he wrote that Hawks brilliantly depicted the city’s “glamorous yet grubby” underworld—full of drug hints, voyeurism, and morally questionable relationships. Of Lauren Bacall’s performance, he quipped that she was “an adolescent cougar”—young, dangerous, and irresistibly seductive.

📸 Photo courtesy: Google. ✍️ Excerpts: Google.