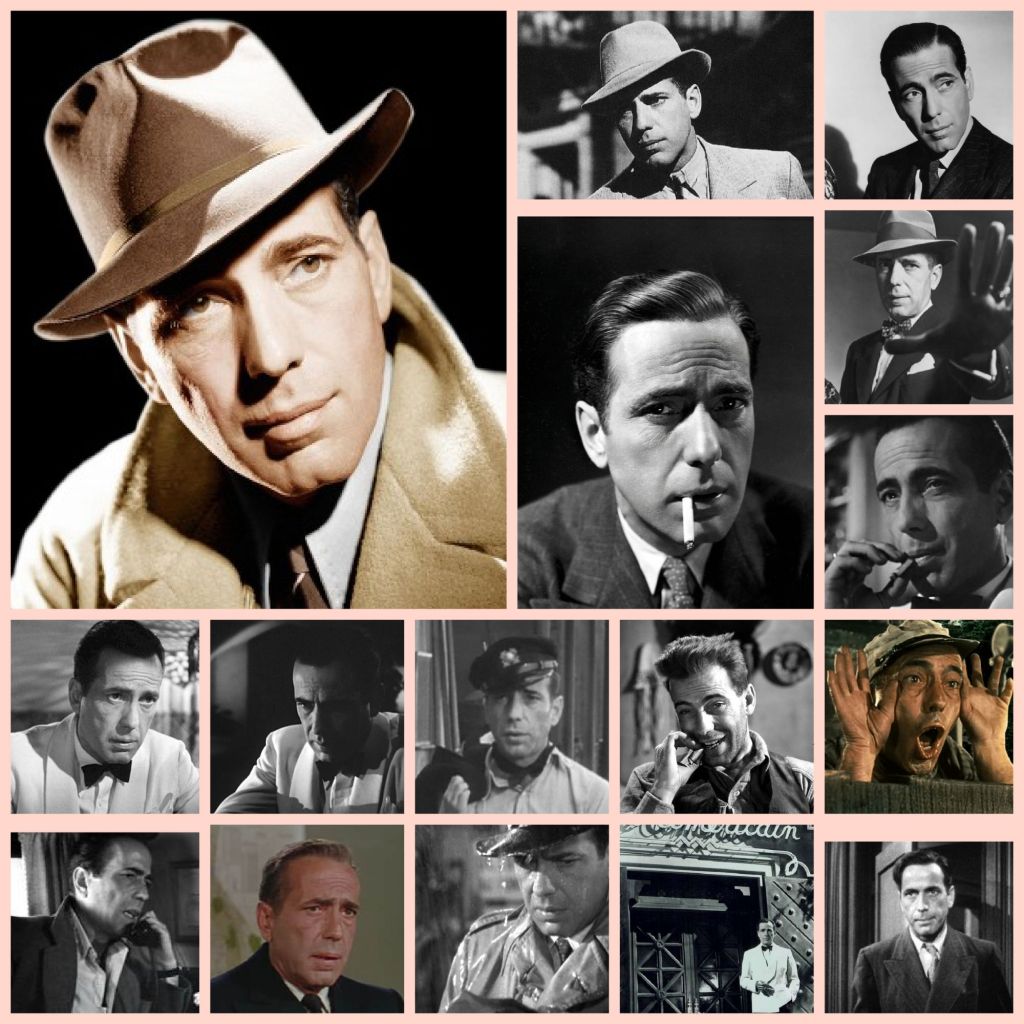

Humphrey Bogart transformed the traditional image of the Hollywood hero during the Golden Age. Restraint, weary honesty, and moral firmness defined his screen persona. He became immortal through Sam Spade in The Maltese Falcon and Rick Blaine in Casablanca, and won the Academy Award for The African Queen.

Slightly solitary yet morally steadfast, Bogart stands as the finest example of the introverted hero.

The true power of Bogart’s acting lay not in words, but in pauses. The way he held a cigarette, the tired glance in his eyes, and his controlled, understated voice shaped characters that were tough, ironic, and unshakable. His dialogue carried intelligent sarcasm and restraint, making his characters feel deeply real. In Dark Passage, he is unseen for nearly 35 minutes—only his deep, steady voice is heard. Even without his face, that voice alone establishes identity, emotion, and trust, proving the timeless strength of his vocal presence.

Though Bogart’s exterior appeared hard and rugged, his shy, warm smile revealed his true charm. That gentle softness in his eyes gave humanity, tenderness, and emotional depth to otherwise stern characters, one of the key reasons his screen presence remains immortal.

Bogart’s rise was shaped by chance. He came into the spotlight with Duke Mantee in The Petrified Forest, a role he received due to Leslie Howard’s intervention. The success led to a Warner Bros. contract, marking the beginning of his remarkable ascent and enduring Hollywood legacy.

In The Petrified Forest, Duke Mantee is a ruthless, dangerous fugitive driven by fear, which he projects onto others as terror. He has no connection to dreams, culture, or beauty—his world is defined purely by survival and brute force. This role proved decisive in Bogart’s career, establishing him as a truly frightening villain and opening the doors to his later greatness.

In Bullets or Ballots, Bogart’s Nick “Bugs” Fenner is a cold, ironic, and highly dangerous gangster. For him, the city is a jungle ruled not by laws, but by money, timing, and gunpower. When he smiles, fear spreads; when he falls silent, death feels near. Trust, love, and mercy have no place in his world. This role strongly reinforces Bogart’s early image as a charismatic yet merciless villain.

In Two Against the World, Bogart plays Sherry Scott, a powerful figure in a radio newsroom—hard, cynical, and obsessed solely with getting the “scoop.” His world revolves around sensationalism, manipulating truth, ignoring ethics, and chasing ratings. Sherry Scott is a newsroom shark—devoid of emotion, driven only by microphones, deadlines, and audience numbers. But as the story unfolds, he realizes that a woman’s life is being destroyed by his station’s greed, forcing him to confront the moral cost of his ambition.

For the first time, regret, guilt, and Bogart’s trademark quiet, bitter, slowly awakening moral questions appear in his eyes. He seems to ask: “I was only chasing one thing—winning the news. But what do we gain if we win headlines and lose a human life? I lived hidden behind the microphone… until one moment when the truth turned back toward me. And it hit harder than a bullet.”

In China Clipper, Humphrey Bogart’s Hap Stuart is an ambitious, hot-tempered, and slightly reckless pilot. He conquers the skies with speed, but inside he carries restlessness and ego. Obsessed with his work, he pushes friendship, emotion, and loyalty aside. This is a classic early Bogart archetype: a hard exterior with a buried heart. Only after a shock does Hap truly see himself. China Clipper suggests that conquering the sky is easy—facing oneself on the ground is far harder.

In Isle of Fury, Valentine “Whale” Stevens is a tough, solitary, yet inwardly justice-driven man. Rough on the outside and sensitive within, Bogart conveys the idea of a “heart hidden behind armor” through minimal dialogue, a steady voice, and restrained performance.

In Black Legion, Frank Taylor is an ordinary man pulled into darkness by fear and hatred.

In The Great O’Malley, John Phillips appears as an idealistic young man standing for compassion and social justice.

In Marked Woman, David Graham is a courageous, morally firm district attorney fighting organized crime.

In Kid Galahad, Joe “Red” Kennedy is a selfish, suspicious boxing manager.

In Dead End, “Baby Face” Martin is a desperate, violent gangster—one of Bogart’s harshest and most brutal roles.

In Stand-In, Doug Quintain is a cynical agent who gradually changes through experience.

In Swing Your Lady, Ed Hatch is a tough but fundamentally honest wrestling promoter, played with light comic touches.

In Crime School, Bogart’s Mark Braden is a strict, discipline-driven police officer who initially seems ruthless. Gradually, his humanity and desire for reform emerge. This role marks an important turning point in Bogart’s career—his transition from a rigid enforcer of the law to a sympathetic, responsible hero.

In Men Are Such Fools, Bogart appears as an arrogant but gradually changing advertising executive, a man whose confidence is challenged by experience and self-reflection.

In Racket Busters and The Amazing Dr. Clitterhouse, he plays cold, ruthless criminal leaders, emphasizing calculation, control, and an absence of mercy.

In Angels with Dirty Faces, Bogart is a morally ambiguous, sharp-minded lawyer, operating in the grey zone between legality and corruption. In King of the Underworld, he is a hard, commanding crime boss, yet one shaded with traces of humanity beneath the toughness.

In The Oklahoma Kid, Whip McCord stands out as one of Bogart’s most brutal Western villains—violent, sadistic, and driven purely by power.

In You Can’t Get Away with Murder, Bogart’s Frank Wilson is an ambitious but morally weak young man who slowly slides into crime for power, money, and convenience, only to become trapped by his own actions. The role strongly reflects the early Bogart pattern of an “ordinary man turning criminal.”

In Dark Victory, Michael O’Leary is calm, compassionate, and responsible, a doctor who balances professional honesty with human kindness while delivering painful truths to the heroine. This performance contrasts sharply with Bogart’s usual hard-edged image, revealing quiet understanding and emotional steadiness.

In The Roaring Twenties, Bogart’s George Hally is a cold, ambitious, and merciless gangster who rises during Prohibition. His cruelty and ego ultimately destroy him, making this one of Bogart’s most powerful villain roles, with violence and menace lurking beneath a controlled voice.

In The Return of Doctor X, Bogart plays Dr. Morris Xavier (Marshall Quesne), a mysterious and terrifying scientist who toys with death and science. Cold, strange, and almost inhuman, this is one of the rare horror roles of his career and completely unlike his usual realistic persona.

In Invisible Stripes, he portrays a man who tries to reform but remains trapped by circumstance; in They Drive by Night, a hardworking, struggling hero; in Virginia City and It All Came True, cold and ruthless criminals; and in Brother Orchid, a tough man capable of change, played with humor and warmth.

Together, these roles clearly trace Bogart’s evolution, from brutal villains and morally compromised men to humanized, complex protagonists, marking one of the most compelling transformations in classical Hollywood cinema.

In High Sierra, Humphrey Bogart’s Roy Earle is a weary, seasoned criminal dreaming of one last big job and a fresh start. But the world has changed, and Roy can no longer adapt to it. Hard on the outside yet lonely and deeply sensitive within, he struggles against circumstance and fate. This role truly transformed Bogart into a leading man and marked the birth of the noir anti-hero.

In The Wagons Roll at Night, Bogart appears as an unstable and violent villain; in The Maltese Falcon, as the morally hard-edged noir hero Sam Spade; in All Through the Night, a clever underworld figure who gradually becomes a patriot; in The Big Shot, a wronged and tragic hero; and in Across the Pacific, a cool-headed, daring patriot.

Rick Blaine is the soul of Casablanca. A war-weary American expatriate, broken by love and disillusionment, he runs Rick’s Café Américain in Casablanca. On the surface he is detached, cynical, and famously claims, “I stick my neck out for nobody.” He tries to remain distant from politics, war, and emotion alike.

But this neutrality is an illusion. His past love with Ilsa Lund in Paris proves that the human being within him is still alive. When Ilsa re-enters his life, Rick’s inner conflict erupts—caught between anger, love, pain, and sacrifice. His smile remains controlled, his voice calm, yet his eyes reveal an unspoken tenderness.

In the end, Rick makes a choice greater than his personal sorrow. He helps Ilsa escape safely with her husband, realizing that something larger than private love is at stake. This act of sacrifice makes him a true hero. Rick Blaine embodies a hard outer shell concealing deep compassion—a man who loses love yet stands by his values.

That is why Rick is not merely a romantic hero, but an enduring cinematic symbol. No matter how much the world changes, Rick Blaine still stands in that shadowy café corner—cool, solitary, yet inwardly alive. He lets go of love, but never forgets it. The Paris night has ended, but the piano continues to play. The unspoken love in his eyes pauses time, and the selfless clarity of his decision defines him as a hero. In Casablanca, Rick is the man who chooses duty over love, speaks through silence, and lives forever in memory.

In Action in the North Atlantic, Humphrey Bogart’s Lt. Joe Rossi is an ordinary, duty-bound U.S. Navy officer during World War II. He is not a glamorous hero, but a man who quietly does his job amid freezing seas and the constant threat of German U-boats. Rossi’s strength lies not in flashy bravery, but in a cool head, discipline, and faith in teamwork. He speaks little, yet makes the right decisions when it matters most. Through this role, Bogart pays tribute to the real, unsung heroes of war—those who fought not on celebrated battlefields, but in the dark, icy waters of the North Atlantic.

In Sahara, Sergeant Joe Gunn is considered one of Bogart’s most humane and leadership-driven roles. A tank commander stranded in the North African desert, he faces dwindling water, manpower, and hope. Gunn is not a hero of grand speeches; he is calm, practical, and responsible. He holds together soldiers from different nations and backgrounds, understanding that in war, humanity and cooperation are the true weapons. Bogart’s steady voice and the tired yet unyielding resolve on his face give the character real weight. Joe Gunn is not a lone, hard-edged hero, but a soldier who remains human even in conflict—and that is why he endures in memory.

In Thank Your Lucky Stars, Bogart does not play a fictional character but appears as himself. Made during wartime, the film is a musical, patriotic production, and Bogart appears not as a hero or a criminal, but as a representative of Hollywood. His screen time is brief but effective. The familiar tough, serious Bogart here feels lighter, more human, and even slightly humorous. It presents a different side of his image—not a star, but a citizen; not a role, but a man. This appearance shows that during the war, Bogart was not only a screen hero, but also a reassuring presence for audiences, a voice that offered comfort and hope.

In Passage to Marseille, Humphrey Bogart’s Jean Matrac is a fierce, determined, and rebellious figure. Wrongly convicted, he escapes a brutal prison and becomes a fighter for the Free French. Matrac is not a born hero but a warrior shaped by circumstance. Injustice, humiliation, and suffering have hardened him, yet the inner fire of moral conviction still burns. Through Bogart’s rough voice and controlled restraint, we sense the character’s inner flame. The role suggests that the struggle for freedom does not begin on the battlefield—it begins within. Matrac embodies Bogart’s toughness, longing for liberty, and quiet courage.

In To Have and Have Not, Harry Morgan is Bogart’s classic cool, soft-spoken, yet deeply principled hero. A boat captain in Martinique, he initially lives by the rule of “I don’t stick my neck out for anybody,” keeping himself away from war, politics, and danger. But injustice and human suffering refuse to let him remain detached. Circumstance—and love, in the form of Lauren Bacall’s Slim—slowly draw him from neutrality into involvement. Beneath Harry’s hard exterior lie humanity, courage, and responsibility. This role distills Bogart’s essential screen persona: few words, great meaning; a cold face, but a living heart.

Harry Morgan’s inner reflection:

The bar was dim, the night soft and quiet, and you spoke like a whisper that couldn’t quite be caught. Through the cigarette smoke, your half-smile drifted toward me—gentle, alluring, and faintly dangerous. There was romance in that smile, challenge in your words. For one moment—just a moment—you were with me, kid. No rules, no war, no reckoning with tomorrow. That instant brushed the hidden corners of my heart, and the night felt more alive. Harry Morgan stood there, guarded behind a hard face, yet for that brief smile, he was momentarily exposed.

In Conflict, Humphrey Bogart’s Richard Mason is a respectable man hiding criminal intent. Through a cold voice, controlled calm, and uneasy eyes, Bogart powerfully portrays a character’s gradual moral collapse.

In The Big Sleep, Philip Marlowe—played by Humphrey Bogart—is the classic noir detective: weary, solitary, yet deeply principled. He moves through a swamp of crime without ever abandoning his moral code. For Bogart, Marlowe is not just a private eye, but a man who protects his inner light even in darkness. Bogart brings Marlowe alive not through plot twists, but through pauses in his gaze, a faint, knowing smile, and a calm, controlled voice. He solves the case, but never fully reveals himself—and that very incompleteness is his true allure. Even today, Marlowe leaves behind a single clue: however dark the world becomes, do not let your inner light go out.

Marlowe speaks little, but precisely. Suspicion rests in his eyes, cool restraint in his voice, and self-control in his actions. His exchanges with Lauren Bacall crackle with unspoken tension and attraction. In a tangled narrative, Marlowe’s real search is not just for truth, but for staying clean. He both wins and loses—yet stands alone in the end, which is why he remains immortal.

In Dead Reckoning, Bogart is Rip Murdock, a battered but unbroken noir hero, fighting alone for the truth. In The Two Mrs. Carrolls, he plays the opposite extreme: a softly masked, unstable, and terrifying villain. Together, these films reveal Bogart’s power at both ends of noir—moral hero and psychological darkness.

In Dark Passage, Humphrey Bogart plays Vincent Parry, a man falsely accused of murdering his wife and forced to escape prison. His journey revolves around identity, guilt, and redemption. For much of the film, Bogart is unseen; the audience experiences only Parry’s voice and point of view, intensifying his fear, confusion, and hope. After facial surgery, Bogart finally appears on screen, as if reborn. Through a restrained voice, weary eyes, and inward performance, he gives Parry’s loneliness profound depth. Dark Passage is considered one of the most experimental and psychologically rich performances of Bogart’s career.

Vincent Parry’s inner reflection:

Shadows kept following me—no matter how often I changed my name, my face, or the road of my life. I came back with a new face, a new identity, a new future; even the mirror failed to recognize me. But your eyes, yes, those calm, speaking eyes—recognized me in an instant. My face had changed, but my shadow still knew you. Without realizing it, you slipped into the cold corners of my heart along with that shadow. Through the fog of distrust, the quiet warmth in your voice reached me gently, as if the night softened and the darkness learned to smile. Tell me the truth? No matter how far I ran or how well I hid, I could never hide from the eyes that knew me. And perhaps, I never truly wanted to.

In Always Together, Bogart appears briefly as himself— not a full-fledged role, but an early glimpse of the tough, self-assured presence that would later become iconic. It feels like a first step toward the persona that would define his career.

In The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, as Fred C. Dobbs, Bogart creates a terrifying portrait of human collapse driven by greed, suspicion, and madness. By abandoning his star image, he proves he is not merely a heroic figure, but an actor brave enough to confront the darkest corners of human nature.

In Key Largo, Frank McCloud is a weary, quiet observer who wants to avoid conflict, yet stands firm when faced with injustice. Bogart’s restrained dialogue, strength in action, and moral resolve reveal a deeper idea of courage—calm, deliberate, and unyielding.

Frank’s inner reflection:

Outside, the storm raged across the sea; inside Nora’s heart, Frank’s steady gaze echoed. With bullets, wind, and death closing in, it was the gentle touch of Frank’s hand that kept her alive. In that isolated hotel, the fear of losing him ran deeper than the fear hiding in every corner.

In Knock on Any Door, Andrew Morton is a tired but compassionate lawyer who tries to understand the social forces behind crime. Through quiet empathy and restraint, Bogart shifts the focus from the criminal to the system that creates him.

In Tokyo Joe, Joe Barrett is a lonely, emotionally wounded postwar figure—hard on the surface, sensitive within. With few words and a controlled gaze, Bogart portrays a man defeated by life, yet never truly broken.

Joe Barrett’s inner reflection:

Postwar Tokyo was rising from ashes—ruined, silent, yet stubbornly alive. In that changing city, he searched for a way forward. But no matter how much the world changed, the unspoken love in her voice still returned to him like a soft echo. War had shattered both the city and their bond, yet the memory of that gentle voice remained alive in his heart.

In Chain Lightning, Bogart plays a seasoned test pilot weighed down by responsibility. In In a Lonely Place, he exposes an inward, unstable, and dangerous psychological world. In The Enforcer, he is a weary yet resolute district attorney, while in Sirocco he becomes a selfish, morally ambiguous arms dealer. Together, these roles reveal the full range of Bogart’s screen persona—hero, guardian of order, and morally compromised anti-hero.

In The African Queen, Charlie Allnut is disheveled but golden-hearted. Through humor, warmth, and emotional transformation, Bogart breaks his hard-boiled image—and wins the Academy Award for this deeply humane performance.

Charlie’s inner moment:

You stirred my life like a river suddenly thrown into turmoil—swift, forceful, and irreversible. Somewhere in that chaos, without realizing when or how, I began drifting on the breeze of your laughter. Just as a boat changes course when the wind shifts on water, I found myself carried by the warmth of your smile. Your arrival shook my life, yet that same laughter taught my heart how to flow with love—something it took me time to understand.

In Deadline U.S.A., Humphrey Bogart portrays Ed Hutcheson, an aging but relentless newspaper editor who stands his ground in defense of truth and freedom. He is tired, but never defeated; words are his weapon.

Hutcheson’s battle is as much against the mafia as it is for the survival of journalism itself. Even on the final day of a dying newspaper, he publishes the truth without fear. With a firm voice, direct gaze, and controlled intensity, Bogart embodies a watchdog of democracy, proving that courage does not require a gun to be powerful.

Ed Hutcheson’s inner moment:

The city feels as if it’s collapsing—street chaos never stops, and in the pressroom the ticking clock pounds like gunfire in my ears. The deadline breathes down my neck; the ink is still wet, the type hot from the press. Yet only one story echoes in my mind, and it isn’t meant for print. Governments fall, criminals run, headlines scream—what’s new? The real truth is this: the trust people place in you is never “breaking news.” It must be guarded quietly, right up to the final print.

In Battle Circus, Humphrey Bogart plays Major Jed Webbe—a seasoned, exhausted, yet deeply responsible military doctor working against the backdrop of the Korean War. He does not face bullets on the battlefield, but he fights a daily battle to save the lives of wounded soldiers.

Jed Webbe is tough, cynical, and emotionally guarded; war has hardened him. Yet beneath that armor, humanity, compassion, and the need for love remain alive. His relationship with June Allyson’s character unfolds cautiously amid wartime uncertainty, restrained yet profoundly felt.

This role represents Bogart’s mature phase: a hero who does not issue commands from a pedestal, but fulfills his duty while quietly enduring suffering. Battle Circus suggests that true heroism exists not only on the battlefield, but in wounds, silent endurance, and human empathy.

In Beat the Devil, Billy Dannreuther is a clever but unreliable adventurer—neither hero nor villain. Through irony and deliberately offbeat performance, Bogart playfully dismantles his own star image, which is precisely why the film became a cult classic.

In The Caine Mutiny, Philip Queeg is a naval officer whose rigid discipline conceals fear and psychological fragility. Moving beyond simple hero–villain definitions, Bogart portrays a deeply human tragedy—an honest, unsettling study of a mind under pressure.

The storm raged outside on the sea, but the true tempest broke within Captain Queeg’s mind—of fear, suspicion, and guilt. His every failure was judged not by shouted accusations, but by the silent testimony of steady, watchful eyes. The ship survived, the sea grew calm, yet the unspoken verdict delivered by those eyes continues to echo long after.

In Sabrina, Linus Larrabee is a cold industrialist who slowly learns to accept love; in The Barefoot Contessa, a weary, truth-seeing director; in We’re No Angels, a hardened exterior sheltering deep humanity; in The Left Hand of God, a man moving from deception toward moral rebirth; and in The Desperate Hours, a desperate criminal who evokes uneasy sympathy. Together, these roles testify to Bogart’s mature, humane, and multidimensional artistry.

In The Harder They Fall, Eddie Willis is a man trapped in corruption and exploitation, consumed by guilt. In standing up for the truth at the end, Bogart embodies moral awakening and remorse with a powerful sense of exhaustion—his final screen performance leaving behind an image of hard-earned conscience and quiet reckoning.

His partnership with Lauren Bacall became one of the most iconic pairings in Hollywood history. What began on the set of To Have and Have Not blossomed into a real-life relationship. Despite a significant age difference, their chemistry felt natural, intelligent, and deeply mature.

Humphrey Bogart passed away in 1957 due to cancer, yet his influence remains undiminished. The weary detective, the morally complex hero, the emotionally guarded man—Bogart shaped the very template of these archetypes. He never tried to be a perfect hero; instead, he discovered greatness through imperfection.

Bogart… in the quiet intensity of your eyes and the dry warmth of your voice, you gave new meaning to love, courage, and loneliness. In Hollywood’s black-and-white dreams, you were not merely a star—you were the hazy, smoke-filled air in which love could lose itself and the shadow of crime could turn poetic. You are gone, Bogie, but the calm, defiant, and unspoken tenderness you left on screen still lives softly in the deepest corners of the heart. In every glance, every smile, every “Here’s looking at you, kid,” an immortal poem continues to breathe.

Humphrey Bogart was not just an actor; he was a feeling, an attitude, and a shadow forever etched into the history of cinema.

📸 Photo Courtesy: Google ✍️ Excerpts: Google