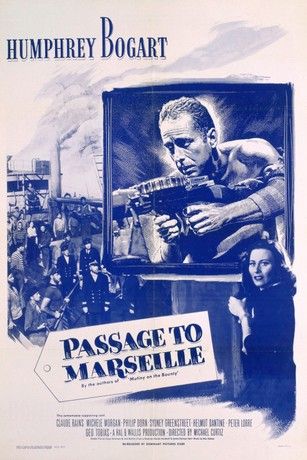

Passage to Marseille (also known as Message to Marseille) is a 1944 American war film produced by Warner Bros. The film was directed by Michael Curtiz, with a screenplay by Casey Robinson and Jack Moffitt, based on the novel Sans Patrie (Men Without Country) by Charles Nordhoff and James Norman Hall. The music was composed by Max Steiner, and the cinematography was by James Wong Howe.

The film opens during the Second World War at an air base in England, where Free French Captain Freycinet recounts to a journalist the story of the French airmen stationed there.

A second flashback takes place in Cayenne, in French Guiana, within a French penal colony, while a third flashback reveals the background of the central character Jean Matrac, a newspaper publisher who is falsely accused of murder in order to silence him.

In 1942, journalist Manning arrives at a British RAF base in England, seeking information about the Free French forces fighting against the Germans. At the base, a squadron of French bomber pilots is preparing for a mission under the command of Captain Freycinet (played by Claude Rains). Manning becomes particularly interested in one gunner, Jean Matrac, prompting Freycinet to begin narrating Matrac’s extraordinary story.

Based on the novel by Charles Nordhoff and James Norman Hall and dedicated to the Fighting French, the story unfolds through multiple flashbacks. In his narration, Freycinet goes back several months to a voyage across the Atlantic, during which the ship he was traveling on rescues a group of men adrift in a lifeboat. Under questioning, the men admit they are escaped prisoners from Devil’s Island. Though stateless and exiled, they are driven by a fierce determination to return to France and fight for their homeland.

Two years earlier, just before France’s defeat at the hands of the Germans, five men are found drifting in a small boat in the Caribbean Sea. They are spotted by the tramp steamer Ville de Nancy. These five men—Marius, Garou, Petit, Renault, and their leader Matrac—are rescued and taken aboard a French cargo ship commanded by Captain Malo.

At first, they claim to be French–Venezuelan miners returning to their homeland to fight for France. However, under questioning by Captain Freycinet, they eventually confess that they are in fact escaped prisoners from the French penal colony on Devil’s Island (Cayenne, French Guiana).

These prisoners had been inspired by a former convict named Grandpère, a man deeply charged with patriotism, who urged them to fight for France in her hour of need. Before Grandpère, the prisoners recount the story of Matrac’s tragic experiences in prewar France, in order to convince him that Matrac should be entrusted with the leadership of their escape.

Matrac was a revolutionary-minded newspaper publisher who fought against injustice. He had firmly opposed the Munich Pact, and in order to silence his voice, a conspiracy was devised to frame him on false charges of murder and remove him from the public sphere.

By the time the Ville de Nancy reaches the port of Marseille, France has already surrendered to Nazi Germany, and the collaborationist Vichy government has come to power. Upon receiving this news, Captain Malo conveys it to his crew in deeply emotional words and secretly decides to divert the ship to Britain rather than hand over its valuable cargo to the Germans.

A Vichy sympathizer among the passengers, Major Duval, attempts to seize control of the ship, but this mutiny is thwarted largely due to the crucial assistance of the escaped prisoners. Another Vichy supporter, Jourdain, succeeds in signaling the ship’s position to a Nazi bomber. The bomber subsequently attacks the vessel; however, it is shot down by gunfire from the fugitive prisoners. In the course of this clash, Marius loses his life.

After reaching England, the surviving prisoners join the Free French bomber squadron.

As Freycinet concludes his story, the squadron is returning from a mission over France. Renault’s bomber arrives late, because on every return flight Matrac had been permitted to drop a letter over his family home in German-occupied France. Through these letters, his bond with his wife Paula and the child he had never seen was kept alive.

At last, Renault’s aircraft lands at the base. It is riddled with heavy gunfire damage, and Matrac has been killed in action. At Matrac’s funeral, Freycinet reads aloud the final letter Matrac had written for his son—a letter that never reached its destination. It expresses a father’s dream of a better, freer, and safer world to be built after the war. He tells his son that this freedom has been bought at the price of blood, and that its preservation is the responsibility of the next generation.

Yet the letter also acknowledges a harsh truth: human sinful nature has not changed. Darkness is rising again, and evil returns in many forms. Therefore, one must never abandon the struggle for the sake of one’s children and grandchildren. Perhaps iron and fire are no longer required today, but as long as breath remains, one must continue to teach the difference between truth and falsehood, and between right and wrong. True fulfillment, he writes, will come only with the return of Christ, when evil forces will one day be defeated forever. The letter ends on this note of hope, and Freycinet promises that it will be delivered.

According to TCM, in Passage to Marseille Michael Curtiz primarily cast European actors; familiar faces from Casablanca such as Peter Lorre, Sydney Greenstreet, and Claude Rains appear again. Humphrey Bogart and George Tobias are the only major American actors, and they play French roles. Warner Bros. acquired the rights to the novel for what was considered a large sum at the time—$75,000.

Most of the film was shot in California, even though the story is set in foreign locations. Disagreements between Bogart and studio head Jack Warner put the role of Matrac in jeopardy, but after a compromise the film was completed.

In the flight sequences, the Free French Air Force (FAFL) is shown using Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress bombers. In reality, the Free French forces mainly operated medium bombers such as the Martin B-26 Marauder. However, the B-17 was used because it was more familiar to American audiences. Some violent scenes were censored for overseas releases.

.jpg)

Claude Rains plays Captain Freycinet, the commander of an Allied air base in England, preparing to launch bombing missions. John Loder appears as Manning, a journalist who hears from Freycinet the thrilling story of five French prisoners who escaped from Devil’s Island. These men are on their way back to fight for France when, during their journey, news arrives that France has surrendered to Germany.

This film was released at a time when the outcome of the Second World War was still uncertain. France was then under the control of the Vichy government, which was collaborating with the Nazis.

In Passage to Marseille, Humphrey Bogart plays Jean Matrac, a journalist who is falsely imprisoned for speaking out against the Nazis—a man embittered by injustice but who ultimately decides to fight back. After gaining his freedom, he becomes an airman fighting against the Nazis. Peter Lorre (as Marius) accompanies him, and their machine-gun confrontation with a German bomber stands out as one of the film’s highlights. By the end of the film, Matrac sacrifices his life in battle, and his death becomes a powerful symbol of freedom and resistance.

The film feels more action-oriented and closely resembles a prison-escape narrative. Michael Curtiz’s direction, Bogart’s brooding intensity, and Lorre’s presence together make Passage to Marseille a compelling war film.

In a review published in The New York Times on February 17, 1944, Bosley Crowther wrote that a few years earlier the film Devil’s Island had been withdrawn under pressure from the French government, and that Passage to Marseille was almost an act of revenge for that humiliation. He described the film as a harsh and aggressive melodrama that shows how the French people’s love of freedom could not be extinguished even by an oppressive prison system. However, he criticized the film’s use of single, double, and triple flashbacks, arguing that this structure confused the narrative, disrupted continuity, and gave the film an artificial, mechanical quality. In conclusion, he judged it to be a well-intentioned film trapped within its own technical complexities.

By contrast, writing for TCM on September 27, 2002, Joseph D’Onofrio offered a more positive assessment. He felt that Curtiz achieved a rarely seen sense of realism here. The semi-documentary style, the unexpected deaths of major characters, and the sacrifices made by French citizens for their country’s freedom set the film apart. The complex flashback structure effectively reveals both the personal and patriotic dimensions of the struggle. Despite Curtiz’s famously tough temperament, his perfectionism paid off: strong performances, an evocative atmosphere, and financial success (a profit of over one million dollars at the time) all worked in the film’s favor. Moreover, it proved successful as a morale-boosting propaganda film that entertained while inspiring its audience.

📸 Photo courtesy: Google. ✍️ Excerpts: Google.