Night People is a 1954 American thriller film directed, produced, and co-written by Nunnally Johnson. The story was also developed with the involvement of noted theatrical producer Jed Harris.

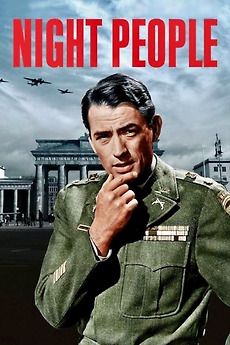

The film stars Gregory Peck, Broderick Crawford, Anita Björk, and Buddy Ebsen in leading roles.

The story is set in Berlin during the Allied occupation following World War II. The postwar political tension, covert operations, and atmosphere of instability strongly shape the narrative. Against the backdrop of the Cold War, the plot follows Colonel Steve Van Dyke, a seasoned American military officer, who skillfully handles a dangerous and complex prisoner/person exchange to secure the release of the son of a powerful industrialist serving as a GI (American soldier). Navigating political pressure, espionage tactics, and moral dilemmas, Van Dyke ultimately brings the operation to completion.

An American soldier stationed in West Berlin, Corporal John Leatherby (Ted Avery), is kidnapped while returning after escorting his German girlfriend home. Soviet authorities deny any involvement through their intermediary, Colonel Lodejinski—who is, in reality, a secret agent working for American and British intelligence.

Meanwhile, John’s father, Charles Leatherby, a wealthy and influential industrialist from Toledo, attempts to secure his son’s swift return by using his connections within the Eisenhower administration and powerful U.S. senators. He travels to West Berlin and pressures State Department and military officials to act immediately, insisting that the crisis be resolved by offering the Soviets a large monetary bribe.

At the same time, the eccentric yet astute provost marshal of the American sector, Lieutenant Colonel Steve Van Dyke (Gregory Peck), is contacted by his former lover and East German intelligence source, “Hoffy” Hoffmeier (Anita Björk). Hoffmeier suggests that John Leatherby has been kidnapped by Soviet or East German authorities, who plan to exchange him for a West Berlin couple, Herr and Frau Schindler.

With the situation growing increasingly complex and no viable alternative available, Van Dyke reluctantly allows Hoffmeier to proceed with arranging the exchange. This decision intensifies the political pressure, espionage maneuvers, and the clash of human emotions at the heart of the story.

After a tense meeting with Leatherby, Steve Van Dyke invites him to dinner at the Katacombe restaurant. Ostensibly, the meeting is meant to discuss the proposed exchange, but in reality Van Dyke is trying to make Leatherby understand the human cost of the deal.

He reveals the identities of the restaurant’s piano player and her husband, explaining that they are in fact Herr and Frau Schindler, the couple slated for the exchange. It emerges that the elderly husband was blinded by Nazi atrocities. Disturbed by the realization that sending them back would amount to condemning them to death, Leatherby is visibly shaken, yet he remains adamant that the exchange must go forward.

Van Dyke has the couple arrested. Following their arrest, they attempt suicide by ingesting strychnine and are rushed in critical condition to an American military hospital.

At the hospital, a shocking truth comes to light. The piano player is actually Rachel Cameron (Jill Esmond), an English expatriate and MI6 intelligence operative. Her husband is revealed to be General Gerd von Kratzenow (Anton Farber), an anti-Nazi conspirator who had been imprisoned and brutally tortured by the Nazi regime. Living under the assumed name Schindler, the couple has been hiding for their lives.

Cameron explains that they are not being pursued directly by the Soviets, but by former Nazi agents responsible for von Kratzenow’s torture—men who are now operating in the service of the Eastern Bloc.

Meanwhile, on another front, Van Dyke prepares to secretly extract Colonel Lodejinski and his family to the United States. Unfortunately, Lodejinski’s covert ties to America are exposed. Faced with inevitable capture and disgrace, he makes an extreme and tragic choice—murdering his entire family before taking his own life.

This episode sharply underscores the film’s themes of moral ambiguity, postwar politics, and human tragedy.

Around the same time, Van Dyke learns from a colleague in military intelligence that his trusted source, “Hoffy” Hoffmeier, is in fact unreliable and an impostor working for the Eastern Bloc. Van Dyke suspects that Hoffmeier was responsible for exposing Lodejinski as an American intelligence asset. Despite this, he allows her to continue arranging the agreed-upon exchange.

Van Dyke deceives Hoffmeier by claiming that General von Kratzenow has died from strychnine poisoning. Using this false information, he engineers a one-for-one exchange between Corporal John Leatherby and Rachel Cameron.

To carry out the exchange, Van Dyke arranges for an ambulance to cross from East Berlin into West Berlin. However, State Department official Hobart (Max Showalter) warns Van Dyke that if the operation fails, the U.S. government will disavow his actions and deny responsibility.

To protect American and British intelligence assets and ensure the success of the exchange, as Corporal Leatherby is removed from the ambulance, Van Dyke knocks Hoffmeier unconscious and presents her as Rachel Cameron. The American military police immediately force the ambulance to return to East Berlin, preventing the accompanying escort from confirming the true identity of the patient.

After Corporal Leatherby is safely returned, his father Charles Leatherby warmly congratulates Van Dyke. The experience leaves him visibly more humble and introspective than before.

The film is built on a strong idea and a capable cast. Its basic concept is powerful and rich in dramatic potential. For Van Dyke, the rescue is a delicate game of back-channel diplomacy, informants, Soviet intermediaries, and covert exchanges; for the wealthy father, the problem seems simple—he is willing to pay any ransom required. This clash of approaches disrupts a carefully planned strategy and leads to a direct confrontation between Van Dyke and Leatherby.

Gregory Peck and Broderick Crawford both command formidable screen presence, making their battle of wills compelling to watch. Supporting characters, particularly Anita Björk, add further possibilities for diplomatic intrigue and espionage. The story by Jed Harris and Tom Reed appears solid and promising.

Veteran screenwriter Nunnally Johnson was seeking the right project to make his directorial debut and approached Darryl F. Zanuck about directing Night People. Zanuck was receptive but cautioned that Gregory Peck held contractual veto power over the choice of director and might object to an inexperienced filmmaker. However, Peck and Johnson were longtime friends, and Peck had complete confidence in him, immediately approving Johnson’s debut as director. Johnson later remarked that he felt little apprehension about directing, as he had excellent actors, a skilled cinematographer, and a strong editor to rely on.

Throughout the film, Gregory Peck gives a committed performance. As Lieutenant Colonel Steve Van Dyke, he delivers a restrained yet sharp portrayal. Unlike his usual image as a cultured, morally upright hero, this role is more aggressive, ironic, and pragmatic, a shift Peck handles with ease.

Peck’s dialogue delivery is crisp and edged with sarcasm; the calm firmness of his voice and well-timed barbs give the character authority. His controlled gestures, steady gaze, and economical movements convey a seasoned military officer and skilled tactician. Peck subtly expresses the inner strain of a man caught between moral conflict, human cost, and political pressure, and despite the restraint, his confidence and charisma consistently command the screen.

Overall, Peck’s performance in Night People reveals a different facet of his career, presenting a tougher, sharper, and more intellectually driven hero. This is precisely why Peck later remarked that the role of Steve Van Dyke was one of his personal favorites.

For Night People, Jed Harris and Tom Reed received an Academy Award nomination for Best Story, underscoring the strength of the film’s central idea.

The film was released in New York on March 12, 1954, where it met with generally favorable and positive critical reception.

At the time of its release, Variety magazine described the film as a “top-quality, suspenseful, cloak-and-dagger thriller.” The review also praised the director’s command over production, direction, and screenplay, noting that he had achieved a “clean triple” by excelling in all three areas.

📸 Photo courtesy: Google ✍️ Excerpts: Google