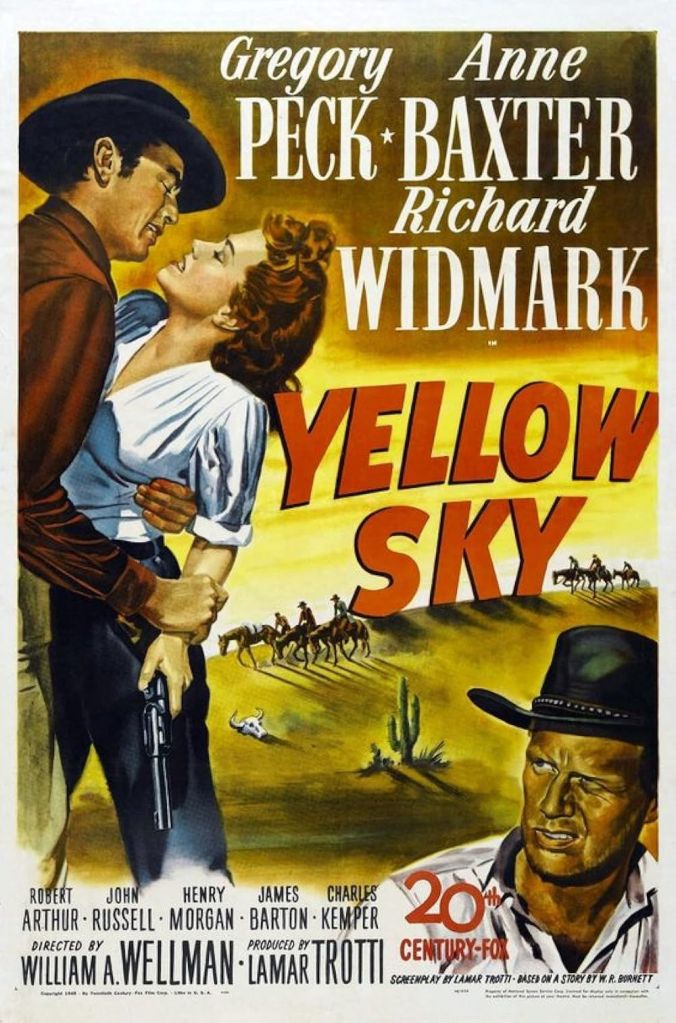

Yellow Sky (1948) is an American Western directed by William A. Wellman, starring Gregory Peck, Richard Widmark, and Anne Baxter. The film is based on an unpublished novel by W. R. Burnett.

Set in 1867, the story follows a group of ruthless outlaws who flee into the desert after robbing a bank. Exhausted and tormented by thirst, they eventually stumble upon a deserted ghost town called Yellow Sky. There, they encounter only two inhabitants: a tough, sharp-shooting tomboy known as Mike and her elderly grandfather.

The arrival of the gang creates an atmosphere of intense tension. As the outlaws discover the possibility of hidden gold, suspicion, greed, betrayal, and a struggle for power begin to surface. Against the stark and desolate backdrop, the film gradually explores the conflict between good and evil within human nature, as each character faces a severe test of fate and morality.

In 1867, a gang of outlaws led by James “Stretch” Dawson (Gregory Peck) robs a bank. With soldiers in pursuit, they decide to escape across the vast salt flats of Death Valley. Enduring extreme heat and unbearable thirst, and nearly collapsing from exhaustion, they eventually arrive at a deserted ghost town called Yellow Sky.

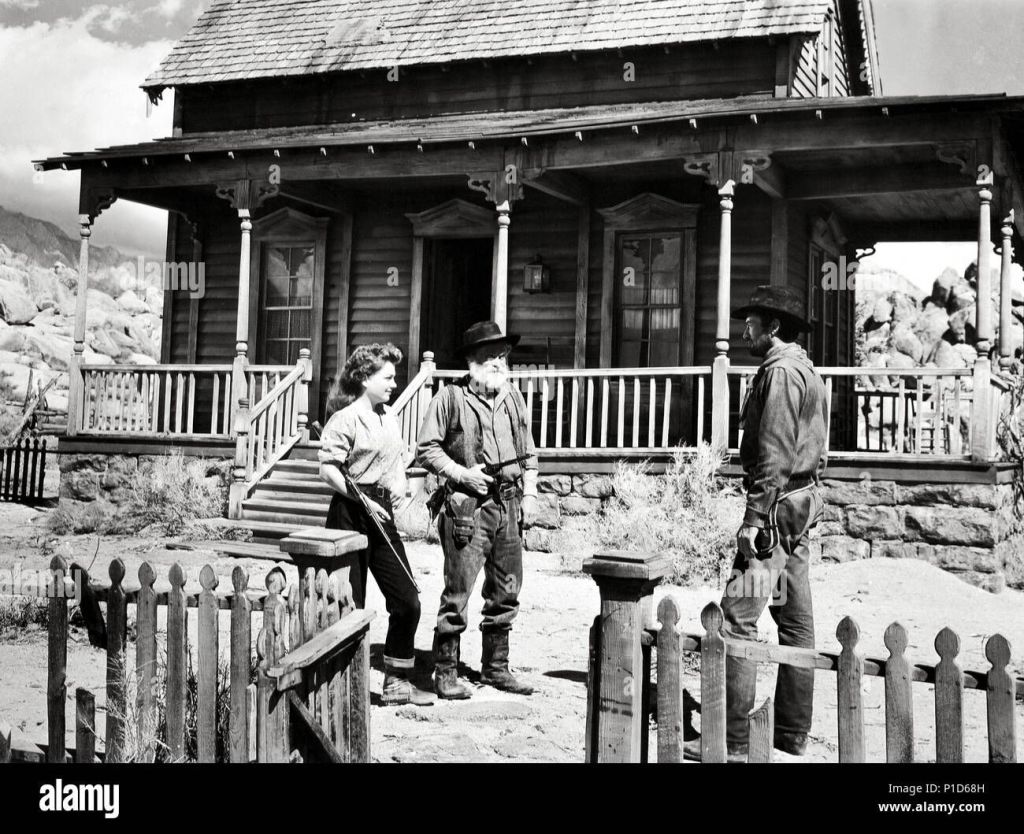

The town has only two inhabitants: a tough and strong-willed young woman named Mike (Anne Baxter) and her grandfather, an elderly prospector (James Barton). Stretch begins to feel attracted to Mike. Meanwhile, the gang’s gambler, Dude (Richard Widmark), snoops around and discovers that the old man has secretly been mining gold. He informs the others, but Stretch initially pays little attention.

The next day, Mike and her grandfather head toward the hills. At the same time, tension rises between Stretch and Dude over leadership of the gang. During a confrontation between the two men, Mike opens fire on them. However, a ricocheted bullet fragment accidentally injures her grandfather in the leg. With the situation growing desperate, Mike is ultimately forced to surrender.

Back at the house, the grandfather is persuaded to negotiate over his gold. It is estimated to be worth around $50,000, and an agreement is made to divide it among them.

Meanwhile, at the watering hole, Lengthy (John Russell) forcibly grabs Mike and attempts to assault her. The young Bull Run (Robert Arthur) intervenes to protect her, but Lengthy overpowers him and holds him underwater. Stretch arrives just in time, rescues Bull Run, and teaches Lengthy a lesson by forcing his head beneath the water until he is nearly drowned.

That night, Stretch cleans himself up and returns to Mike, attempting to make a better impression. He assures Mike and her grandfather that he will honor the agreement and even swears on the Bible to keep his word—unaware that Dude is secretly listening.

The next day, while the gang is mining for gold, a large group of Apaches appears nearby, creating a tense situation. The grandfather informs Stretch that he has persuaded his Apache friends to return to their reservation and has told them nothing about the gang.

Grateful that the old man did not incite the Apaches to attack, Stretch tells his men that the gold will be divided equally among everyone. However, Dude has already turned the others against him. Determined to seize all the gold for himself, Dude draws his gun and shoots at Stretch.

A fierce gunfight erupts among the rocks as the remaining gang members turn against their leader. During the shootout, Stretch is wounded. At that moment, Mike arrives and takes the injured Stretch back to her home to tend to him.

If Stretch survives, the remaining gang members fear they will have to live under his shadow forever. Determined to finish him off, they surround the house, and the situation becomes tense and decisive.

During the ensuing gunfire, the gang believes Stretch has been killed. Now intent on keeping all the gold for himself, Dude turns on Lengthy and shoots at him, but misses. In the chaos, Dude also shoots Bull Run, who is gravely wounded and dies. Shocked by Bull Run’s death, Walrus (Charles Kemper) and Half Pint (Harry Morgan) have a change of heart and decide to stand by Stretch.

Stretch then pursues Dude and Lengthy as they flee into the town and take refuge in the saloon. A deadly three-way shootout follows, heightening the tension to its peak.

A frightened Mike runs into the saloon and finds Dude and Lengthy dead, while Stretch lies unconscious—but still alive.

After recovering from his injuries, Stretch, along with Walrus and Half Pint (now wearing Dude’s clothes), decides to return the stolen money. The three men go back to the bank and repay what they had robbed. Finally, they ride off on horseback with Mike and her grandfather, setting out toward a new beginning.

The studio purchased W. R. Burnett’s unpublished novel in November 1947 for $35,000. All drafts of the screenplay were written by Lamar Trotti.

Directed by William A. Wellman, Yellow Sky is a Western that powerfully blends themes of isolation, desperation, and greed with touches of film noir. Leadership of the hardened outlaw gang is shaped by the conflict between “Stretch” and “Dude.”

Driven by a desperate search for water, the gang arrives at the deserted ghost town of Yellow Sky. Ironically, a weathered sign at the town’s entrance reads, “The fastest growing town in the territory!”

The only remaining inhabitants are a tough young woman, Mike, and her grandfather. Their presence leads the outlaws to suspect that gold may be nearby, creating tension within the gang. Ultimately, Stretch—who begins to develop feelings for Mike—must choose between gold and love.

Visually and aurally, the film is a feast: mist-covered mountains, murmuring streams, the blinding white salt flats of the desert, and barns and shacks glowing under the moonlight in Yellow Sky. An early scene in which Stretch behaves aggressively and inappropriately toward Mike (knocking her to the ground) gradually gives way to tenderness, as the moonlight casts a romantic glow over the lifeless town.

From the opening horseback chase to the climactic shootout in the evening wind, Yellow Sky finds beauty within brutality and paints a striking poetic quality amid its rugged harshness.

In the desert, the intense heat, swirling dust storms, or the yellowish sky at sunset create an atmosphere of desolation, danger, and quiet despair.

In Yellow Sky, the title refers to an abandoned ghost town, and symbolically it represents isolation, greed, and the moral conflict unfolding within the characters.

In this film, Gregory Peck appears both dangerous and charismatic, while Anne Baxter matches him with equal strength and presence. Yellow Sky is not merely a Western; it is a subtle psychological study of its characters and their inner conflicts.

Mike (Anne Baxter) is a fiercely strong-willed, self-respecting, and determined young woman. She strives to prove herself as capable and tough as any man. That is why she rejects her real name, “Constance Mae,” and adopts the masculine nickname “Mike.” Her moral code is firm and unwavering; she refuses to bow before anyone. She and her grandfather take pride in the fact that she was raised among the Apaches. She loves her grandfather deeply and is willing to go to any extreme for him. Though she is a tomboy, she possesses a natural feminine allure that draws the attention of several members of the gang.

The tense relationship between Stretch (Gregory Peck) and Mike forms the emotional core of the film. Mike claims to despise all men, yet her reaction to Stretch is different. At first, she responds to him with distrust and anger, but beneath the hostility there is a suppressed attraction. Stretch pursues her, at times behaving harshly, yet he also protects her. In one key moment, when he defends her, a softness briefly appears on her face—marking a turning point in their relationship.

Mike’s inner conflict is portrayed with striking depth. She projects toughness, but inwardly she suppresses her identity as a woman. In a symbolic scene, she looks at a picture of a beautifully dressed woman in her room and tears it apart—an expression of her internal struggle. She has hardened herself to survive in a brutal world, yet gentle emotions continue to stir within her.

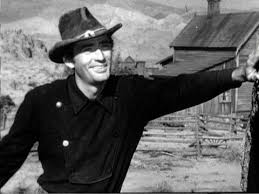

Gregory Peck’s stern yet inwardly conflicted portrayal of Stretch gives the film remarkable depth. Here, he shines as a compelling “bad boy.” After the first forced kiss, the look of disgust in Mike’s eyes unsettles him deeply. The very next day, he appears before her clean-shaven and wearing a fresh shirt—as if consciously trying to earn her respect. This altered appearance signals an inner shift, and Mike’s rigid emotional defenses slowly begin to weaken. His attempt to move from coercion to dignity suggests a meaningful transformation in his character.

At the opposite pole stands Dude (Richard Widmark), a symbol of greed, bitterness, and lust for power. He harbors contempt for women and cares for nothing but gold. When he senses that Stretch is softening toward Mike, he tries to overthrow his leadership. For Dude, gold is the only objective. When Stretch ultimately refuses to harm Mike and her grandfather, breaking the unspoken code of the gang, the others turn against him. Ironically, it is Mike—who initially despised Stretch—who risks her own life to save him.

This shift—from hatred to trust—elevates the film emotionally. In Yellow Sky, the relationship between Mike and Stretch blurs traditional gender boundaries. Both save each other’s lives, overturning the conventional “damsel in distress” trope. In fact, love makes Stretch more vulnerable, and ultimately it is Mike who rescues him—not only physically, but morally. Wellman’s direction emphasizes equality, mutual respect, and sacrifice within their bond. At first, it seems that Stretch saves Mike; in the end, she saves him from his darker instincts.

Thus, the film transcends a simple love story. It becomes a powerful exploration of greed, honor, power dynamics, and moral choice. With strong performances from Anne Baxter and Gregory Peck, Yellow Sky secures a distinct and timeless place within the Western genre.

The film’s cinematography, direction, and screenplay received particular praise from critics.

Christopher Tookey wrote, “…this is an outstanding Western. Wellman’s atmospheric direction—making effective use of natural sounds, and Joseph MacDonald’s bold, high-contrast cinematography make the film distinctive. Lamar Trotti’s screenplay is one that aspiring writers should study; despite its sparing use of dialogue, it won an award from the Writers Guild of America.”

Bosley Crowther observed, “Gunfire, fistfights, and emotional entanglements are all rendered in an excellent, realistic Western style. William A. Wellman sustains tension from beginning to end.” He further noted that the story “operates mainly on the level of action and a somewhat constructed love story. But within this popular framework, it is made tough, tense, and effective… The film proves to be solid and exciting entertainment throughout its running time.”

TV Guide commented, “Despite its unexpected ending, the quality of this superbly photographed and directed Western never diminishes; it may be considered one of the finest examples of the genre. The high-contrast black-and-white cinematography is striking. Though the dialogue is minimal, it is all the more effective; the story is told primarily through visuals. The score is excellent—introducing each scene before gradually receding to allow natural sounds to enhance the realism.”

The film’s success led to a radio adaptation. Gregory Peck reprised his role, and director William A. Wellman served as host. The adaptation was broadcast on July 15, 1949, on NBC Radio’s Screen Directors Playhouse.

📸 Photo courtesy: Google ✍️ Sources: Google