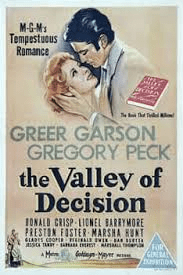

The Valley of Decision is a 1945 American drama directed by Tay Garnett. Set against the backdrop of industrial transformation in 1870s Pittsburgh, the film powerfully portrays social inequality, class divisions, and the conflict between laborers and mill owners. Based on a novel by Marcia Davenport, the film stars Greer Garson and Gregory Peck in the lead roles.

High above the city stands the grand mansion of steel magnate William Scott, symbolizing wealth and power, while below, near the meeting point of the Monongahela and Allegheny rivers, his massive steel mill burns day and night. At the foot of the mill lies a crowded workers’ settlement where Irish immigrants struggle to survive.

Mary Rafferty lives there with her disabled father, Patrick “Pat” Rafferty, and her sister Kate Shannon. One morning, Mary learns she has been hired as a maid in the Scott household. Her father reacts with anger and bitterness—he had been crippled in an accident at the same mill. “That man left me crippled for life,” he says, harboring deep resentment toward the Scott family.

Yet poverty leaves Mary with little choice. Caught between self-respect and necessity, she accepts the job to support her family. Meanwhile, Jim Brennan, a mill worker with strong union beliefs, asks to rent a vacant room in their home—his presence bringing not just a lodger, but the growing tension of labor unrest.

On Mary’s very first day at work, Paul Scott (Gregory Peck), William Scott’s son, returns home from London. Cheerfully whistling as he climbs the stairs, he is warmly welcomed by his mother Clarissa and his siblings—Ted, Constance, and William Jr. The house bustles with preparations for a grand dinner.

The housekeeper Julia instructs Mary on how to arrange cutlery, plates, and wine glasses, and how to behave before distinguished guests. Constance and Ted tease her lightly. Surrounded by glittering luxury yet conscious of invisible social barriers, Mary becomes aware that this world of privilege is entirely new to her.

Amid the rush, Paul speaks to her for the first time. “You’re new here? What’s your name?” There is curiosity in his voice, but no arrogance. In that brief moment, two different worlds meet—the regal mansion on the hill and the fiery shadows of the steel mills below.

Suddenly, Mary is told that she must be the one to announce dinner to the guests. The thought of speaking before such distinguished people frightens her. Her voice softens, and no one pays attention. At that moment, Paul quietly understands the situation and firmly announces, “Dinner is served.”

Though this may seem like a small gesture, it reveals Paul’s character beautifully. He protects Mary from embarrassment, stands by her side, and reinforces her words so her confidence does not falter. In this simple act, his sensitive, supportive, and caring nature becomes clear.

During the dinner, the men begin discussing business. William Scott firmly declares that he will not enter into a partnership with Andrew Carnegie. He wants to keep his steel mill independent and under family control. To him, the mill is not merely a business venture but a matter of pride and tradition.

Paul speaks passionately, saying that steel runs in their blood. To him, the mill has a heart and soul; selling it would be like destroying something living. He believes the steel industry is the spirit of their family—meant not only for profit, but to create something lasting and noble.

Inspired by this vision, Paul proposes adopting the “Open Hearth” method he observed in Germany. With better temperature control and refining processes, it would produce higher-quality steel. Before the older generation, content with traditional methods, this modern idea appears bold and ambitious. Paul begins experimenting, modernizing the furnace in an effort to give the industry a new and progressive future.

Jim Brennan arrives at Mary’s home carrying a model of the new “Open Hearth” furnace. However, Pat Rafferty—crippled in a mill accident—erupts in anger. Bitter toward the Scott family, he recounts the injustice suffered by workers and angrily drives Paul away. Paul leaves quietly. A hurt and conflicted Mary follows him up the hill and softly sings for him. Looking down at the blazing mills below, Paul says the furnaces are alive to him; the industry is not merely about profit but about his very soul. Mary is reminded of the same passionate words she had heard at that first dinner. In that moment, their relationship deepens and takes on a new meaning.

Through her courtesy, loyalty, and sense of duty, Mary gradually becomes almost a part of the Scott family. Meanwhile, Constance Scott secretly attempts to elope one night with Giles, Earl of Moulton, but Mary intervenes and prevents the plan. Touched by her devotion, Mrs. Scott invites Mary to accompany her on a sea voyage to Boston for the wedding of William Junior (Willie Scott).

On the return journey from Boston, Mary keeps a careful watch over Constance. During the voyage, she notices Constance speaking through the cabin window to a gentleman below. Smiling playfully, Constance says, “He’s not a stranger—he’s the Earl of Moulton.” In such moments, the youthful impulsiveness of the household stands in contrast to Mary’s growing sense of responsibility and maturity.

Quiet moments on the deck during the sea voyage bring Paul and Mary closer than ever. In that calm and intimate setting, Paul kisses her for the first time and firmly says, “I won’t apologize for kissing you… I’m glad I did.” In that instant, their feelings become undeniable. Yet Mary’s heart is burdened by social barriers, loyalty to the family, and her own self-respect. Though she loves him, she asks him to keep his distance. This confession of love marks a deeper and more complicated turning point in their relationship.

As Paul’s repeated attempts to perfect the “Open Hearth” furnace fail, he grows discouraged. Mary encourages him by telling the story of “Bruce and the Spider,” inspiring him not to give up. Strengthened by her faith in him, Paul once again declares his love: “There is nothing in this world greater than what I feel for you.” He asks her to marry him. Still, Mary’s inner conflict remains intense—for her, self-respect and duty are as important as love.

Mary gives notice and resigns from her position with the Scott family. Meanwhile, Constance and Giles inform William that they are married and offer Mary a position in England. With Clarissa’s permission, Mary decides to leave for England. She bids farewell to the family, but not to Paul.

In England, Mary struggles with her pride and emotions. Though she longs for Paul, she does not reply to his letters, and distance grows between them. Constance senses her feelings and urges her to respond, but Mary’s hesitation persists. At the same time, Clarissa tells her husband that Paul still loves Mary deeply. Paul himself confesses his love to his father. At last, William Scott realizes that Mary is the true foundation of Paul’s happiness. He brings her back and grants his approval for their marriage. Mary returns, torn between fear, hope, and love, and their union finally receives the family’s acceptance. Love blossoms anew.

Meanwhile, Paul’s “Open Hearth” experiment succeeds. Proudly, he declares, “This is the finest steel in the world.” But almost immediately, a labor strike erupts. Patrick Rafferty, now a forceful union leader, takes an aggressive stand. The class conflict begins to overshadow personal relationships.

When Mary returns to Pittsburgh, the strike intensifies. An angry mob throws stones at the Scotts’ home, and tensions reach a breaking point. Enraged, Paul decides to bring in strikebreakers. But Mary knows that not all the workers support violence. She leaves the Scotts’ house and goes to the Flats to reason with union leader Jim Brennan, insisting that reconciliation is still possible. Eventually, both sides agree to meet on the bridge.

At the center of the bridge, William Scott listens to the workers’ demands and agrees to wage increases, safety measures, and recognition of the union. For a brief moment, hope for peace emerges. But when strikebreakers arrive, violence erupts. In the chaos, both Pat and William are killed. The class struggle leaves both families shattered with immeasurable grief. The memory of the blood-stained bridge weighs heavily on Mary, leaving her devastated.

Paul expresses his boundless love for Mary and pleads with her to marry him, insisting that they have nothing left in their lives except each other. But Mary, grounded in reality, thinks about the consequences their relationship would have on the Scott family. “Shall I make them a laughingstock before the world?” she asks. In that question, her self-respect, gratitude, and inner conflict are clearly revealed. She is also haunted by guilt over her father’s death, feeling that she has betrayed his trust. Despite her love, she steps back, unable to cross the barriers of social class, family honor, and her own sense of dignity. Heartbroken, Mary decides to walk away from Paul, and from that moment, their lives take separate paths.

Ten years pass. Paul marries Louise and settles into domestic life; they have a son, but there is little warmth or love in the marriage. An aging Clarissa (Mrs. Scott) continues to meet Mary and ultimately leaves her share of the mill to Mary in her will, convinced that Mary alone truly understands how to preserve the family’s legacy, the industry, and its bond with the workers. After Clarissa’s death, disagreements arise again within the family. At a business meeting, Paul’s siblings are eager to sell their shares, and a substantial offer of two million dollars is made. However, Mary firmly opposes selling the mill and persuades Constance to retain her share as well. To her, the mill is not merely a profit-making enterprise but a legacy, an identity, and a tradition deeply connected to the lives of countless workers. As she speaks with conviction, a quiet smile appears on Paul’s face.

In the end, Paul comes to realize the emptiness of his lifeless marriage and decides to part ways with Louise, allowing Mary to return to the center of his life. After years of struggle, sacrifice, and sorrow, Paul and Mary are finally reunited. The love that had remained unfulfilled for so long at last finds its true direction. Like the tale of the Irishman Bruce, no matter how many times one fails, perseverance ultimately leads to success. Love, understanding, and the preservation of tradition triumph, and The Valley of Decision concludes with a gentle yet steadfast ray of hope.

The film stands as a powerful study of moral choices and clashing personalities. Through each character’s selfish or selfless actions, their true nature is revealed. The conflict between love, duty, and social justice unfolds in a deeply moving and emotionally resonant manner.

Greer Garson’s portrayal of Mary presents not merely a young woman in love, but a strong and dignified character who balances self-respect, duty, and social awareness. Through her restrained and nuanced performance, she powerfully conveys Mary’s inner conflict between love and loyalty to family. In scenes depicting strikes and class conflict, the pain reflected in her eyes reaches the audience directly. Garson brings both compassion and moral strength to the role, and her regal composure makes Mary the moral center of the film.

Although relatively new at the time, Gregory Peck drew great attention with his portrayal of the romantic and intense Paul. His casual, confident entrance—often whistling—adds charm and vitality to the character. Peck plays Paul with passion, bringing to life an idealistic young man deeply devoted to the steel industry and driven by emotion. The determination visible on his face when speaking about the “Open Hearth” furnace, as well as his despair in moments of failure, are expressed with striking effectiveness. In romantic scenes, his straightforward and sincere style reflects Paul’s longing to rise above social barriers. Peck presents Paul not just as the son of an industrialist, but as a young man torn by inner conflict and bound by tradition.

Garson gives the film its emotional depth, while Peck contributes romantic energy and dramatic intensity. Together, their powerful performances make the film a memorable work of Hollywood’s Golden Age.

The film earned Greer Garson a nomination for the Academy Award for Best Actress in a Leading Role, and it was also nominated for the Academy Award for Best Music, Scoring of a Dramatic or Comedy Picture. In addition, it won the prestigious Photoplay Gold Medal Award for Film of the Year. These honors stand as formal recognition of the film’s artistic quality, compelling performances, and memorable music.

📸 Photo courtesy: Google ✍️ Sources: Google